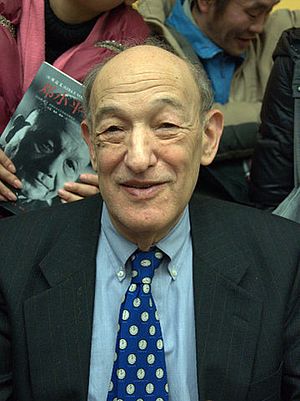

Professor Ezra F. Vogel is Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences Emeritus at Harvard University. He has spent his career researching the politics, society and economy of China and Japan. He is best known for his books Japan as Number One: Lessons for America (1979), One Step Ahead in China: Guangdong under Reform (1989), Is Japan Still Number One? (2000), and Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (2011). He recently spoke Emanuel Pastreich.

Many are expressing great concern these days about the considerable rise in the tensions between China and Japan over the last ten years. Do you think that this rise in tensions was an inevitable course of events? Or are there steps that could have been taken to avoid this ratcheting up of tensions?

Conflicts between China and Japan are not inevitable. Unfortunately, leaders in both countries have chosen policies that have exacerbated tensions. After the Tiananmen incident and the debate about democratization in the 1980s, Chinese leaders were most concerned about what the attitudes of youth towards government would be. Would youth be loyal to the government or would they adopt a rebellious attitude.

But once they introduced patriotic education, then it was inevitable that historical issues, and a focus on World War II would become the primary lens through which Chinese perceived Japan. For their part, the Japanese have not done all they could have to make it absolutely clear for their neighbors, and for the world, that they have fundamentally rejected the attitudes and policies that led to World War II.

I think it’s ridiculous to assume that changes in the policy for Japanese self-defense forces policy mean that Japan is going down the path of militarism. The entire situation is quite different than the 1930s and 1940s and there are many institutional barriers to the militarism of that era in place. There is much that Japan is doing, and could be doing, as a member of international efforts for peacekeeping and there is no need to be concerned about these contributions.

At the same time, for rather complicated reasons having to do with domestic politics, many Japanese leaders have not been as forthright as they should about Japan’s position, especially with regards to the history of World War II. Perhaps they are thinking about the impression that young people have about Japan and so they try to play down the mistakes of the past. But although building up confidence in Japan’s past at home makes sense to them, it leaves them open to criticisms from Korea and China.

The relationship of Japan with its neighbors China and Korea is complicated. Although the emotions roiled up by the declarations of Abe Shinzo have created major rifts, we also find enormous cooperation, such as the China-Korea-Japan Trilateral Cooperation Secretariat. There are many conferences on technology, business and government in which we see cooperation between these three nations becoming increasingly routine. You would never guess as to this reality if you just read the newspapers.

The leader of any country must balance domestic political pressures with the realities of the international situation. A leader must help the citizens of his country think positively about their country and take pride in their work. This responsibility is a significant one and it is a natural one. In the case of Japan, there is a real feeling among many Japanese that they have been asked to apologize too many times. They see that other former colonial powers, including countries like Belgium, Great Britain, and even the United States with regards to the Philippines and Hawaii, have taken aggressive actions against other nations. But Japanese scratch their heads and wonder why it is just Japan that must apologize.

This feeling is widespread among many Japanese and Abe is reflecting that perspective as a politician. Although we may disagree about the long-term motivations behind those policies, it is a fact that the educational system, and the infrastructure, was significantly modernized in both Taiwan and Korea during the colonial period. From a Japanese perspective, the complexity of Japan’s role is ignored and rather Japan is being treated unfairly.

The leader of Japan has to balance the need to respond to the domestic response to the complaints of China and Korea with the reality of international relations and international business. Japanese businessmen, and politicians, know that it is in the long-range interests of their countries to develop strong economic ties with their neighborhoods.

Abe Shinzo’s grandfather, Kishi Nobusuke, was deeply involved in the development of Manchuria during the colonial period and Abe clearly feels a direct connection with that period. But as a politician he has sometimes underestimated the response to his actions. For example, he did not anticipate the outcry in China, Korea and the West regarding his visit to the Yasukuni Shrine during his first administration.

Abe is trying to balance his own personal sense of pride in Japan with the practical diplomatic and geopolitical issues that Japan faces, especially concerning the history issue. His recent moves show increasing sophistication and I think he is laying the groundwork for a significant improvement in the Japanese relations with Korea and China.

The consensus for an improvement in Japan’s relations with its neighbors is strong. Some argue that it is rather in the perceived national interests of China to keep Japan on the defensive with regards to historical issues. Chinese leaders may be tempted to use the history of World War II to keep Japan on its toes, but at the same time we find that many Chinese see the significant advantages of meaningful engagement with Japan.

I have met many thoughtful Chinese, especially young people, who honestly embrace a vision of a peaceful, integrated Northeast Asia and are developing relationship with Japan and Korea. They are not hyped up on anti-Japanese propaganda, but are very committed to serious engagement.

China, Japan and Korea are immense economies with extremely complex political structures. It is hard to make any meaningful generalizations, although people do try.

But in the ideological discourse within China concerning the Second World War, there were either patriots or traitors. There was nothing possible in between. But the discourse on regional affairs in East Asia is growing increasingly sophisticated and we find many cosmopolitan people in China, Japan, and Korea who realize that these countries should work together, and advocate for collaboration. We have a generation of Chinese and Koreans who have had frequent occasions to visit Japan, collaborate with Japanese colleagues and see Japan on a daily basis.

They know that the descriptions of Japan that appear in the Chinese press are not accurate. They bring balance to debate on China’s relations with Japan.

We find a complex mixture of responses in China. There are many cosmopolitan people in China who have a balanced view of contemporary affairs. They do not pay attention to the sensationalist reports about Japan in the mass media and maintain close ties with Japanese colleagues. They have a long-term view, but when the domestic political situation is such, they feel they must also step forward to offer their criticisms of Japan. But that does not mean all Chinese are swept over by emotions, or anger at Japan.

The question we need to think about is how the top leaders in each country can lead the big, complicated ships of state in an overall good direction. We cannot expect them to be miracle workers, and we cannot expect them to simply drop all patriotic rhetoric. Nonetheless, there are certain low-key steps they can taken that telegraph restraint to the other party. Personally, I think there are signs that we can expect some substantial progress in Sino-Japanese relations and that Abe will meet with Xi Jinping in one format or another.

In the case of the celebrations of the seventieth anniversary of the “victory over Japan” do you think there is any format or approach that would have convinced a Japanese prime minister that it would be possible to attend?

I think there was a manner in which the event could have been carried out that would have made it possible for Abe to attend. But given the current mood in Beijing and Tokyo, and the inevitable domestic responses, it would be very awkward for any Japanese leader to attend at this moment. If I were in Abe’s position, I would be very careful about what would be said concerning historical issues at any meeting I attend. That said, given the passage of time, it is entirely possible to put together a summit meeting between Abe and Xi that would be sufficiently balanced so as to avoid domestic criticism for both leaders.

Many Americans are drawn to China as the great rising power in the world economy. Even Donald Trump, as he attacks China, speaks in glowing terms about the business opportunities available in China.

The dominant opinion in mainstream America, including Washington D.C. and much of the business community, is that we have to work with China.

China is a major power and China has shown consistently that it is possible to reach agreements, to work with them. The process will be complicated, no matter who is president. We are talking about the two largest economies and they, like other countries, have competitive urges. Some of the geopolitical issues are going to be extremely difficult to resolve.

In any country, the military has a responsibility to defend the country and to be prepared for conflict. That need will be there, no matter how good exchanges are, and we should not take the calculation of security issues by the military as an indication that close relations are impossible.

The question is HOW you find a way to work with the other country, not CAN you find a way. Given the depth of collaboration between the Chinese and Americans now in business, academics, student life, tourism, etc. we are already deeply intertwined. We need to preserve and build on those ties.

We are in a very different environment than that of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. There are those in the United States and in China who for financial reasons, political aspirations, or patriotic sentiment want to get tough with the other country.

There are plenty of people in the United States who feel some frustration with China, and often for legitimate reasons, but the news media picks up these threads and blows them up into garish stories that will attract viewers or readers. In my view, those who scream out in the media about China are not offering a meaningful policy for the United States. We certainly saw that sort of “bashing” of Japan in a previous age. Trade, finance, technology and security are complex issues that require a balanced, long-term, educated dialog.

And what do you make of Korea’s current role in the world? Korea has become visible over the last ten years, but it still does not quite have the established reputation of other developed nations. What do you see Korea’s role going forward in East Asia and in the world?

In fact, Korea has been very central to the geopolitical order in Northeast Asia for centuries. A number of interests in Asia come together in Korea because it is so centrally located and it is tied directly to the Japanese, the Chinese and the American economy. Historically, Chinese culture was introduced to Japan through Korea.

These days Koreans are assuming that their future will be influenced by a strong China. They are putting a lot of thought into how to position themselves relative to China: How can Korea develop closer ties appropriate to greater economic integration and at the same time maintain their independence? There are no simple answers and Koreans have wrestled with this problem for centuries. There have been Chinese, and Japanese, invasions by a variety of dynasties.

Obviously strong relations with Japan and the United States are essential to reduce the possibility that Korea will be swallowed up by the Chinese economy if China continues to expand. But although the alliance with the United States is important to most Koreans, it is also true that the Chinese have been quite successful in enlisting Koreans in campaigns to criticize Japan for its actions in World War II.

The Koreans are very responsive to the criticisms of Japan and the history issue is increasingly dominant in politics, even as those with living memories fade away. The most prominent issue is that of the comfort women. The issue of comfort women and their experience has become a rallying call that evokes the entirety of the Japanese occupation after 1910. The suffering of Koreans during the Japanese occupation and because of forced labor in Japan during World War II have still have tremendous emotional significance despite the passage of time.

At the same time, we see good relations between Koreans and Japanese at many levels and the inflammatory statements of politicians on both sides obscures significant cooperation and cultural exchange. Many Koreans have extremely close Japanese friends and speak Japanese fluently. When Koreans actually visit Japan, they often have a pleasant experience and feel very much at home. So the depth of personal contacts between Koreans and Japanese is much greater than the newspaper headlines highlighting anti-Japanese sentiment convey.

How are China, Japan and Korea been described in American discussions of foreign policy in Washington D.C. or at Harvard?

One of the problems for the United States diplomacy is the logic of the election cycle. It’s very difficult for the Obama administration to talk about long-term issues when Washington politics is focused on the next election. But Xi Jinping can talk about the next seven years. Overall, the members of the U.S. administration are pleased that Abe is making an effort to increase Japan’s burdens for international security. There is a group of policymakers in Washington D.C. who are deeply concerned about broad national security issues, and they’re pleased with what they see as a very forward-looking position on the part of the Abe administration. Overall Abe’s visit to the United States was quite successful. U.S.-Japan relations are quite strong. There are many who hope that Park Geun-hye will take steps to assert that the U.S.-ROK relationship is strong.

In the case of Xi Jinping, there is a broad-based effort in Washington to find a way to work with China. This effort is complicated, however, by the manner in which China has behaved rather strongly at times. China’s claims of the islands in the South China Sea are broadly perceived, even by those who support closer collaboration, as being excessive. So there is considerable concern about how Obama will behave during the summit meeting. In a sense, he will have to think very carefully about domestic politics because China, and its growing economic power, is increasingly a domestic issue.

What is your take on the recent economic downturn in China?

I think the downturn will take a little wind out of the sails for China. The Washington crowd is less impressed by Chinese economic power. But I think that the articles reporting China’s demise are a bit premature. If you look at the Chinese stock market, it’s so much higher than it was a year ago. And I think that perspective needs to be reflected in the media. Whatever the slowdown, the Chinese economy is increasingly powerful and that continuing trend is the most likely scenario. All the discussion about the collapse of the Chinese stock market is a tempest in a teapot and unlikely to be a long-term problem.

That said, China does face some serious challenges. From the aging population to the serious pollution of water, China will have to confront some difficult domestic issues over the next decade.

South Korea remains a strong ally of the United States and cooperation is quite good, but there is some nervousness in certain circles about warming relations between China and South Korea. President Park’s recent visit to Beijing on the seventieth anniversary of the “victory over Japan” raised concerns, especially in light of close U.S. cooperation with Japan.

The long-term status of the Korean peninsula and the response to North Korea by the United States, Japan and South Korea are important topics that will continue to demand attention. Unfortunately, with only a year and a half left, Obama cannot do any long-term planning. But the future of the Korean Peninsula is extremely complex and will require much discussion between China, the United States, South Korea and Japan.

With the expanding conflict in the Middle East and the disagreements with Russia, I wonder how much time American policymakers can devote to long-term thinking about the Korean peninsula.

Inevitably it will only be a tiny group in Washington D.C. that has the expertise and the immediate concern to focus on the Korean Peninsula. Unfortunately, the experts are rarely those who have political power in Washington D.C. Nonetheless, there are some smart people who do think seriously about long-term issues and will have their chance to contribute to the debate.

Emanuel Pastreich is Director of the Asia Institute. The original version of this article is available at Asia Today. This is the first of an interview series organized by the Asia Institute.