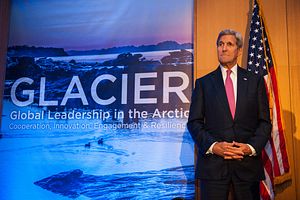

On Sunday and Monday, foreign ministers and other international leaders met in Anchorage, Alaska to attend the Conference on Global Leadership in the Arctic: Cooperation, Innovation, Engagement, and Resilience (GLACIER). The State Department described the meeting as “focused on changes in the Arctic and global implications of those changes, climate resilience and adaptation planning, and strengthening coordination on Arctic issues.”

The United States is currently the chair of the Arctic Council, a grouping of the eight Arctic States (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States) plus a dozen states with permanent observers status, including China, India, Japan, South Korea, and Singapore. The U.S. made it clear that the GLACIER conference was not an official Arctic Council event, but said the meetings would “focus attention on the challenges and opportunities that the Arctic Council intends to address.”

As a sign of the importance the United States placed on the Alaska forum, President Barack Obama attended. He used the conference as a platform for urging swifter action to combat climate change. “Climate change is no longer some far-off problem; it is happening here, it is happening now,” Obama said. “We’re not acting fast enough.”

He also used his speech to focus attention on the need for a global agreement to be reached at this year’s UN climate meeting in Paris: “This year, in Paris has to be the year that the world finally reaches an agreement to protect the one planet that we’ve got while we still can.”

After the conference, the representatives of the Arctic Council members signed a joint statement affirming “our commitment to take urgent action to slow the pace of warming in the Arctic.” The Arctic states were joined by 10 of the 12 Arctic Council permanent observers – with China and India as the holdouts.

Most of the joint statement contained a litany of climate change-related issues already seen in the Arctic, including statistics on melting glaciers and ice sheets and warming temperatures, as well as the impact on Arctic communities. In terms of state commitments, however, there wasn’t much to see. The signatories affirmed a “strong determination … to achieve a successful, ambitious outcome at the international climate negotiations in December in Paris this year”; acknowledged the importance of reducing black carbon (soot) and methane emissions; and called for “additional research” on how climate change is impacting the Arctic.

According to CCTV America, China said that it needed more time to review the document before signing. But RT had a different take, saying that China and India “opted not to sign the document” because “reducing emissions entails huge expenditure and loss of economic effectiveness.” (RT also said that Russia had decided not to sign, contradicting other reports).

China is not a member of the Arctic Council, but was added as a permanent observer in 2013. In the two years since then, Beijing has moved rapidly to stake out its interests in the Arctic, particularly when it comes to developing mostly-untapped energy reserves in the region. It is especially interested in being acknowledged as a key actor in the Arctic – though not an Arctic state, China believes the fate of the region is crucial to its national interests. China has begun defining itself as a “near-Arctic state” in the hopes of gaining a larger say in Arctic affairs.

Beijing’s decision to abstain from the joint statement on climate change in the Arctic suggests that it viewed the statement as being in conflict with its Arctic interests, potentially setting the stage for later arguments in the Arctic Council itself about how to balance environmental protection with resource extraction and other development activities.

China’s reaction to the GLACIER conference also sends a worrisome signal about U.S.-China cooperation on climate change. In addition to refusing to sign the statement, China sent a relatively low-level representative. Former Chinese Ambassador to Norway Tang Guoqiang, billed as a “special representative” to China’s foreign minister, headed the delegation from Beijing; most other countries sent either minister-level or deputy-minister-level officials (Russia was another exception, sending only its ambassador to the United States to the event).

Last year, China and the United States surprised the world by unveiling a climate change deal wherein both sides agreed to take concrete steps to move toward clean energy. That, in turn, raised hopes that the December 2015 climate change conference in Paris could successfully unveil a new global roadmap for emissions reductions. Both China and the U.S. have been slow to adopt binding commitments to cut emissions, despite the fact that they are the world’s two largest carbon emitters; their joint cooperation will be crucial to getting a deal done in Paris.

China, in particular, has long held that its status as a still-developing country should make it immune to mandatory cuts (a stance also adopted by India, the other hold-out at the GLACIER conference). 2014 marked a remarkable change in China’s willingness to commit to reducing global emissions, a side effect of China’s “war on pollution” domestically.

Conversely, the failure to come to an agreement at the GLACIER conference sends a troubling signal for the Paris summit, and for U.S.-China cooperation in general.