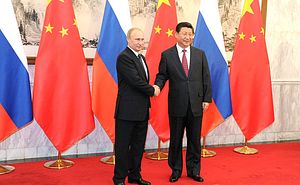

Leaders in Beijing and Moscow have both been making a concerted effort to extend their connections with Central Asia in recent months. In July, Russia hosted the latest BRICS summit as well as a gathering of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Ufa near the border with Kazakhstan. Earlier, in May, on his fifth visit to Russia since becoming president, President Xi Jinping reached an agreement with President Vladimir Putin to coordinate China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative with the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) in Central Asia. While both countries have clear economic incentives to cooperate in this region in the short term, they will need to overcome a number of hurdles to set their partnership on a path that can be sustained further into the future.

In the past year, Russia and its Central Asian neighbors have faced sobering economic challenges. Russia’s GDP contracted by almost 2 percent in the first quarter of 2015, at least in part as a result of the falling price of oil and Western sanctions, and the ruble lost nearly half of its value against the dollar in August 2015 compared with one year earlier. The impact was felt in Central Asia too, given its close economic interdependence with Russia. Both the oil- and gas-exporting nations of Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan saw declining oil and gas revenues, currency devaluation, and reduced gas exports to Russia, a market that is now oversupplied given weakened European demand. Remittances are another source of income suffering strong disruption – the World Bank has estimated that remittances of some Central Asian countries have fallen by as much as 30 percent since last year. This has a dramatic impact when seen in the context of the share remittances that make up of these countries’ GDP, half in the case of Tajikistan.

Meanwhile, China’s trade with the region reached $50 billion in 2014, a figure that exceeded that of Russia for the first time. According to calculations by the authors based on figures from the Heritage Foundation, total Chinese investment in the region reached $30.5 billion between 2005 and the first half of 2014, including an extensive network of oil and gas pipelines, oil and gas exploration, power plant financing, and even electric grid construction in Tajikistan. The China-Central Asia network of pipelines could supply up to 55 billion cubic meters of natural gas to China every year, or more than half of China’s total gas imports.

Central Asia is critical in China’s OBOR initiative, because it holds the immediate entrance of China’s Silk Road Economic Belt, and is itself a significant destination of Chinese investment. But China’s huge investment, especially those in oil and gas in Central Asia, is far from risk free. Russia’s longstanding influence in this region offers the potential to build a mutually beneficial partnership among China, Russia, and the countries of Central Asia. Having Russia in the partnership is especially valuable in securing existing regimes in these former Soviet Union countries, safeguarding China’s long-term investment, a lesson learnt from setbacks in places like Myanmar and Libya. Making it a lasting framework that aligns the political and economic interests of all three parties, however, may prove to be a difficult process.

First, Beijing and Moscow may not share the same vision for Central Asia or for their partnership. At the core of Putin’s ideology the partnership with China is a brand of anti-Western rhetoric, which was particularly acute during the Sino-Russian gas deal and negotiations over the Power of Siberia (POS) natural gas pipeline route to deliver gas from Chayanda oil and gas field to Khabarovsk with a connection to North China. Along with China and Central Asia, Russia is eager to promote the EEU as an alternative to the West, even more so now with the prospect of channeling Chinese capital. But that may not be in line with China’s official position on OBOR and the role of Central Asia. Despite the tensions between the United States and China, China is far from comfortable being in direct confrontation with the United States and the West, and prefers to stay behind Russia’s waving hammer. More importantly, Russian sees Central Asia its own backyard, to be defended against Western expansion in favor of keeping the existing order. China, by contrast, sees Central Asia as a strategic corridor of its OBOR initiative linking the Europe, sharing prosperity and conveying inclusiveness in a changing international order.

Another challenge stems from the geopolitical circumstances under which this partnership was formed. The Ukraine crisis and Russia’s economic difficulty gave China an upper hand in the POS gas route negotiations and in its bid to access Russia’s upstream energy resources. The partnership is formed at a time of Russian economic weakness, and could become a source of resentment. China’s economic support comes into play when Russia’s economy is in peril, but it may not be fully appreciated by the Russian oil industry and politicians once the hard days pass. CNPC, China’s state-owned oil and gas firm, certainly still remembers how, about a decade ago, its two attempts to purchase Russian oil assets and the long expected Angarsk-Daqing oil pipeline agreement went south due to the opposition of Russian politicians and the Russian government’s swing game between China and Japan.

The potential competition for natural gas market share in China between Russia and Central Asia is another potential risk to sustaining this partnership over the long term. Given declining European demand for natural gas since the Ukraine crisis, Russia is inclined to deliver gas from the proposed west Altai route instead of the high profile east POS route, so its surplus production in existing West Siberian fields could be sold, but this would be in direct competition with existing Central Asia-China gas imports. The POS route, awaiting new field development in East Siberia, is what China prefers but is more difficult in terms of construction and operation. However, once completed it could supply exclusively to the northeast Chinese market and even the Far East market of Japan and South Korea without competition from Central Asia. China is already facing a short-term oversupply of natural gas due to slowing growth in demand. Even though many are still confident about China’s long-term demand for natural gas, direct competition between Central Asia and Russia on the western route may not be in the best interests of the partnership.

Finally, there are risks in further engaging Central Asia. This region has enormous security challenges, among them narcotics trafficking, religious radicalism, weak governance, and the threat of terrorism. There are also growing concerns over the successors to the aging leaders of the region’s authoritative regimes. Russia has been the key security partner for these post-Soviet states, but China risks becoming more directly involved politically with a continued deepening of economic relationships. In the context of a continued economic contraction, Russia may have to focus more on securing its own interests and domestic security without regard to those of China. After the Ukraine crisis, how much room Russia still has in the international community to wield its power in Central Asia when needed is questionable. China would do well to approach the partnership with a bit more caution and less fantasy.

Wang Tao is a resident scholar at the Carnegie–Tsinghua Center for Global Policy, where Rachel Yampolsky was a research assistant during the summer of 2015.