China’s Song dynasty (960-1279) was a period of intellectual flowering. The 12th century, in particular, saw the initiation of a Confucian renaissance, the invention of paper money, the development of tea culture and the systemization of the civil service exams, establishing a meritocracy that’s evident still today (something I wrote about in last month’s magazine). The government encouraged agricultural expansion by letting people own whatever barren lands they farmed. Steel plows replaced iron ones, and as food subsequently became more plentiful, China’s population doubled. Additionally, cottage industries such as silk and cash crops such as tea created an economy so advanced that scholars consider it “pre-modern.”

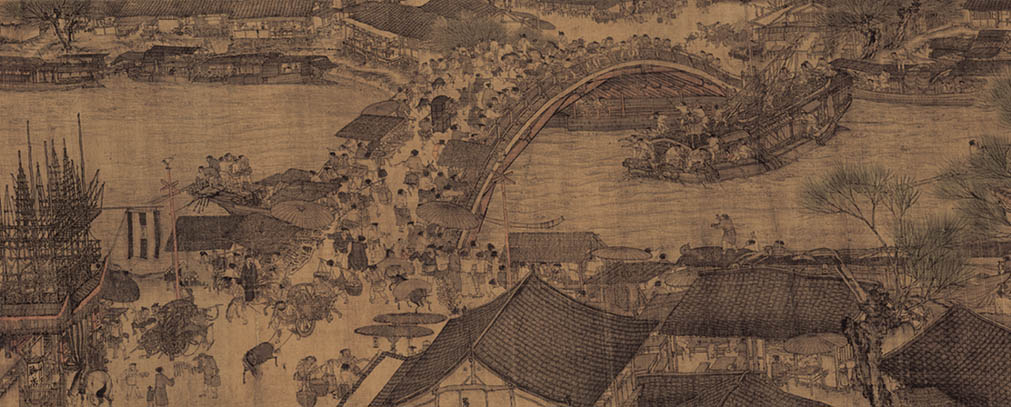

These technological and economic innovations were accompanied by a flowering of artistic genius, including the poetry of Lu You, though none deserve more praise than Zhang Zeduan’s Along the River During Qingming Festival. Painted at the height of the Song dynasty, it displays the capital Kaifeng on one of the busiest days of the year. And it not only vividly depicts the peak of Chinese civilization but also, considering Kaifeng was then the world’s largest city (with roughly 700,000 people), the wonders of 12th century humanity stretched to their limits.

This 17-foot-long masterpiece is packed with personalities. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but the first time I saw it I was reminded of a Where’s Wally? picture book. And while its popularity has earned it the nickname “China’s Mona Lisa,” the similarities end there, for while the Mona Lisa is the fugue perfected, this is life symphonic.

The first movement, if you will, begins on the left, within the city walls. Beneath elegant pines and the slope of tiled roofs we find a shambolic crowd of doctors, jugglers, beggars and monks. A man helps his child walk, possibly for the first time. Two men argue. A serene face peers out at the noise from within a palanquin. Someone draws a bow, testing its pull. Friends relax on a balcony, drinking tea. And atop the majestic city gate, someone quietly watches the busy streets below.

As we leave the city, we pass two men idly chatting against its gate and enter the second movement, where life is less frenetic and the pulsing river now swings into full view. The waters are crowded with boats and all along its banks people recline in restaurants or sell baijiu and tools beside the paths. Then suddenly, the dramatic third movement. A boat hasn’t finished lowering its mast and is moments from crashing into a bridge. People crowd to help. Someone lowers a rope. Arms are outstretched.

Then the scene transitions to the quiet countryside where the river current ripples between trees and you calmly let your eyes drift over the scenery, enjoying the denouement until you reach the end and realize at last what you’ve witnessed: the busiest day in the world’s biggest city, at the climax of China’s greatest era. It is, simply put, an astonishing creation and possibly the greatest painting in Chinese history.

And if you live in Beijing, you’re in luck, because it’s now on display at the Forbidden Palace to celebrate the Palace Museum’s 90th anniversary. The queues are insufferably long, but the wait is worth it, especially considering that the last time it was shown in Beijing was ten years ago, for the Palace Museum’s 80th anniversary.

Reporting on the display, this week Amy Qin of The New York Times reflects on the Chinese public’s “fanatical interest” in the painting. She suggests the fervor to see it has been partly engineered by the government’s support of traditional culture and an increasingly popular “desire to appear cultured.” She quotes calligraphy master Chen Yimo as saying, “no matter how much money you have, if you don’t have culture, then you’re just a tuhao” (one of the vulgar rich).

And while I agree with Chen Yimo, it’s hard for me to see anything but hope in the fact that so many people are flocking to admire such a wonderful work of human creativity, whatever the reason.