This article was first published by 38 North, a blog of the U.S.-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins SAIS. It is republished with kind permission.

When the Soviet Union shocked the world and opened the Space Age on October 4, 1957, it was not a coincidence that its first satellite was launched into orbit on a modified R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). For many observers, that was the message of Sputnik — the rocket that did this can deliver hydrogen bombs to your cities. Nor was the message sent only once. The first 96 Soviet satellite launches were conducted using modified ICBMs, before Russian engineers bothered to design a rocket specifically for space missions. China still hasn’t bothered to field a space launch vehicle (SLV) that isn’t also a ballistic missile. On the other side of the world, every ICBM design the United States has ever put into service has been adapted to launch satellites at some time or another.

So when North Korea launched its first satellite on December 12, 2012, many observers thought the message was clear: the rocket that did this can deliver atomic bombs to your cities. And indeed it can. But is this really the purpose of the Unha-3? Is it an ICBM masquerading as an SLV, or an SLV that might someday be repurposed as a missile? There is precedent for both. Or, as Pyongyang claims, is the Unha-3 intended purely for peaceful space exploration?

There are sound technical reasons for using the same rocket in both applications. The fundamental requirement for an ICBM is to accelerate a hydrogen-bomb-sized payload to roughly 16,000 miles per hour, just above the atmosphere and aimed about 20 degrees above the horizon. To launch a satellite, you want to be a little bit higher, flying horizontally at 18,000 miles per hour. Until your satellites grow larger than your bombs, there is no reason to develop a second rocket, and no way for suspicious outsiders to know for sure what your real goals are.

But if the Unha-3 is intended for use as an ICBM, it’s not a very good one. The second- and third-stage engines don’t have enough thrust to efficiently deliver heavy warheads; a militarized Unha might deliver 800 kilograms of payload to Washington, D.C. The North Koreans can probably make a nuclear warhead that small, but it would be a tight fit. With bigger upper-stage engines, which we know the North Koreans have, they could deliver substantially larger payloads. This would allow bigger and more powerful warheads, more decoys to counter U.S. missile defenses, and a generally tougher and more robust system.

The Unha is also too heavy and cumbersome to be survivable in wartime. Too big for any mobile transporter, it can only be launched from fixed sites. Its highly corrosive liquid propellants require hours of pre-launch preparations. That’s a bad combination for North Korea; their fixed launch sites are going to be watched very closely, and particularly in a crisis, any indication that an ICBM is being prepared for launch could trigger a pre-emptive strike.

The same could be said of the old Soviet R-7. As an ICBM, it was pretty much a dud — the USSR never deployed more than 10, and retired them after less than a decade. As a space launch vehicle, its descendants are still in service today.

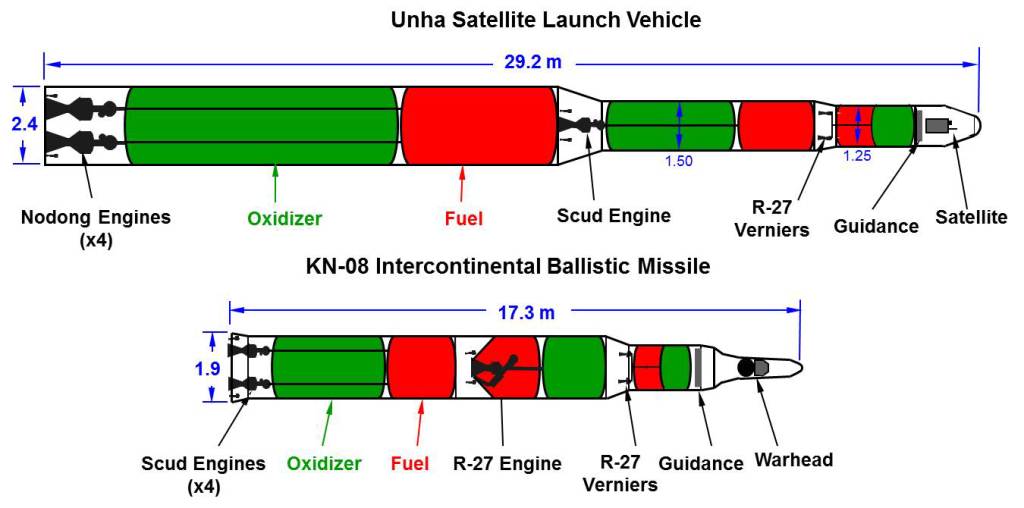

The North Koreans could press the Unha-3 into limited service as an ICBM, just as the USSR did with the R-7 — a temporary measure, until something better is available. They can almost certainly build something better, and they appear to be trying. The KN-08 missile mock-ups, twice paraded through Pyongyang, are exactly the sort of thing a nation like North Korea would build if it wanted to use its eclectic mix of early 1960s rocket technologies to build an ICBM. It is small enough to be mobile and therefore survivable but with the performance (barely) to reach the enemy’s homeland. The Unha-3, by comparison, looks like it was designed to launch satellites rather than warheads.

From a historic perspective, it is worth noting that any ICBM the North Koreans might deploy will owe much to the Unha. ICBMs are necessarily multi-stage rockets, and cleanly separating one stage to ignite another is a surprisingly hard problem. North Korea hasn’t always been able to do this, and finally got it right with the Unha. North Korea does not have any single engine powerful enough to lift an ICBM; the ability to operate multi-engine clusters is also something it learned with the Unha. Earlier missiles used heavy steel tanks and structures; the Unha taught the North Koreans to use lighter aluminum alloys. And its first successful use of high-energy propellants was in the third stage of the Unha. Almost every technology needed to go from crude short-ranged Scud and Nodong missiles to a fully capable ICBM, North Korea learned in the course of developing the Unha.

That’s all history. The key question now, in view of speculation that Pyongyang might launch another rocket, is can the North learn anything more from new Unha-3 launches? Of course, we don’t know if a launch will take place or if it does, whether Pyongyang will use a new and different rocket. But it is still a question worth asking.

If the North Koreans deploy a militarized Unha as an interim ICBM, then every successful flight of that rocket as an SLV will serve to increase the reliability of the ICBM force. Even failed satellite launches would be a learning experience. As the Unha is unlikely to serve as more than an interim ICBM, North Korea may not have time to transfer any valuable lessons from their space launch activities to their ICBM force before the ICBM guys move on to a better missile. But at a minimum, if we see Unha-like missiles sitting in silos presumably aimed at the United States, successful launches of an Unha carrying a satellite would increase the potential threat.

However, it is not clear that these lessons will carry over to any new ICBMs North Korea may try to build. Our current best estimate as is that the KN-08 mobile ICBM, has only the third-stage engine and maybe some guidance hardware in common with the Unha (see the diagram below). Everything else will be similar in concept but different in execution, and the execution is the part that matters. Remember that the legendary ’57 Chevy Bel Air was built by the same people who came out with the “unsafe at any speed” Corvair three years later. No matter how reliable the 2015 Unha turns out to be, the 2020 KN-08 will be an entirely different beast.

What if North Korea does launch an even larger rocket than the Unha in October? That may be its game plan, given construction activities over the past few years modifying the gantry to handle a bigger rocket. What may be good news for North Korea on the satellite launch front — a larger rocket would be more useful for launching satellites — would probably not be useful in helping the North build smaller, mobile ICBMs. The Unha, as noted, is already too big and clumsy to be survivable in wartime.

Still, there is one area where satellite launches might make a major contribution to North Korea’s ICBM program. An ICBM warhead, unlike a satellite, needs to come down as well as go up. North Korea has never demonstrated the ability to build a reentry vehicle that can survive at even half the speed an ICBM would require. If and when they do, what is presently a theoretical threat will become very real and alarming. An SLV gives the North the opportunity to test a reentry vehicle without admitting it is part of a missile.

This could be done by launching the reentry vehicle into Earth’s orbit, perhaps carrying a scientific payload where a missile warhead would go, and bringing it back down in a controlled fashion. Or it could be done by putting the reentry vehicle under an enlarged payload shroud, then “accidentally” cutting the third-stage burn short. Oops, our science experiment accidentally fell into the South Pacific at 15,000 miles an hour. If anyone is paying attention, the fact that a North Korean ship was parked near the impact zone receiving data on the flight’s performance and plucking the remains from the sea will be a dead giveaway.

So we have two warning signs to look for from the North Korean space program. First, using Unha rockets to launch satellites at the same time they are deploying Unha-derived missiles in hardened silos. That might indicate that North Korea is planning to keep an Unha-based ICBM in service long enough to invest in improving its reliability. Second, conducting high-speed reentry vehicle tests during satellite launches. The data from those tests would carry over into any long-range missile program. But it’s not something they can really keep a secret.

Outside of those two areas, if North Korea says its program is for launching satellites, they are probably launching satellites. The usefulness of such launches in terms of developing better ballistic missiles is extremely limited. Of course, we will want to know what kind of satellites; there are certainly possible military dimensions to a North Korean space program. But that’s a question for another day.

John Schilling is an aerospace engineer with more than twenty years of experience, specializing in rocket and spacecraft propulsion and mission analysis. When not studying the nuclear arsenals of foreign dictators, he currently works for the Aerospace Corporation as a specialist in satellite and launch vehicle propulsion systems.