The recent controversy over the reinstatement of state control over history textbooks in South Korea has polarized the nation, the latest in a series of broad movements towards historical revisionism spearheaded by the Blue House since the conservative takeover of power in 2007.

Such polemics is certainly not new in Korean politics, where identity and legitimacy often override debates over policy in terms of voter behavior. The partisan divide over the textbook issue overlaps with larger divergent trajectories between the liberals and conservatives, an irreparable rift which at its core is a conflict over legitimacy.

However, both the timing and the fervor with which the left and the right has concentrated on the textbook issue reveals an underlying political calculus – one that may shape the outcome of the upcoming parliamentary and presidential elections in the next two years.

Politics of Legitimacy

In the Joseon Dynasty, kings whose fathers never occupied the throne often made it their top priority to strengthen their legitimacy by elevating the posthumous status of their paternity to kinghood. This unspoken dynastic principle has been a recurring theme in Korean history, and is even observed in contemporary North Korea.

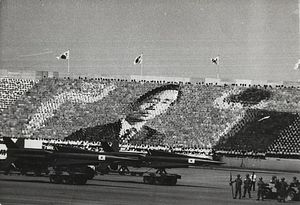

President Park Geun-hye, who has often been criticized for exploiting her father’s legacy in her rise to power, has a similar motivation: to refashion contemporary perceptions about her father, former President Park Chung-hee. The older Park’s 18-year military rule oversaw rapid economic development for South Korea, but was also marked by a blatant crackdown on human rights and democratic freedoms. Another enduring blemish on his record is his service in the Imperial Japanese Army in Manchuria during Japan’s occupation of Korea.

In a rather controversial interview from 1989 with the broadcaster MBC, then-civilian Park Guen-hye clearly stated that she regarded the May 16 coup with which her father came to power as a “revolution to save the nation” – which she claims would have otherwise fallen to communism – and that her most important goal was “to rectify a distorted history” regarding his legacy.

The president’s main ally in pushing through the textbook revision has been the Saenuri party chairperson Kim Moo-sung, whose own father was a prominent businessman during the Japanese occupation and actively encouraged Korean youths to enlist in the Imperial Army to fight in the Pacific war. Kim has been struggling to whitewash his family’s history and downplay his intimate connections to the nation’s corporate and media elite, and thus has been a passionate leader in the New Right movement, the ideological network behind the right wing revisionism.

Elections in Mind

Legitimacy alone, however, can never suffice in Korean politics as a means to attract votes, especially since partisan alignment is firmly embedded within regional networks. Both parties currently face two major obstacles ahead of next year’s elections: to mitigate intra-party conflict between different factions jockeying for nominations, and to attract the moderate vote within a highly polarized electorate.

Within the ruling Saenuri party, Kim’s attempt to build up his own support base has been blockaded by pro-Park loyalists, whose challenge to his authority had been allegedly engineered by the president herself. Yet instead of defying the president like former Saenuri floor leader Yu Seung-min, Kim has opted to win her support by actively supporting the revision.

Park, who was once nicknamed the “queen of elections” during her tenure as party chairman – has exercised unprecedented influence over her party, unmatched by previous civilian South Korean presidents. Her personal clout has been a crucial factor in Saenuri’s successful performance in the recent by-elections, and even salvaged the party when it was struggling from the backlash of the Sewol ferry sinking in the regional elections last year. In order to emerge as the unquestionable conservative nominee of the next presidential elections, Kim must cater to the president’s whims, even at the risk of undermining his own leadership.

Gathering public support has been a more tricky business, especially in light of a recent shift in public opinion away from the revision, due to a rise in dissenting voices from academia, students and even among some conservatives. At the same time however, the history debate has had the effect of concealing voter weariness towards the conservative government, which threatens Saenuri’s chances of retaining power in the future. Kim has also accused the textbooks of having a pro-North bias, in an attempt to capitalize upon the hostility towards the North and paint the opposition as sympathizers to the regime in Pyongyang. Though such MacCarthyist discourse may be rather obsolete and somewhat untrue, anti-North rhetoric has played a powerful role in almost every election since democratization.

The left, on the other hand, still faces an uphill battle to convince the electorate they are ready to govern rather than engage in internal feuds. The main opposition party, New Politics Alliance for Democracy (NPAD), has been teetering on the verge of a massive split since Moon Jae-in was elected its leader in February, and this division may intensify as the elections draw nearer.

Like Kim, Moon also needs to unite his party for the upcoming legislative elections, which will serve as the litmus test for his own presidential candidacy in 2017. He has indeed taken advantage of the broad opposition towards the revision to unite his fragmented party and the leftist camp at large. In a symbolic gesture, he teamed up with the Justice Party chairperson Sim Sang-jeong and former NPAD lawmaker Chun Jung-bae to establish a common front in opposition to the textbook issue. Voices of dissent within his own party from rivals such as Ahn Cheol-soo have also been temporarily silenced due to the national debate.

Despite vigorous leftist opposition to the textbook controversy, it comes as a valuable opportunity to mobilize support among moderates, who the polls say are primarily opposed to the revision. This support may be vital in key symbolic districts such as Daegu – a conservative stronghold, where the NPAD hopes to win its first seat in April next year. His party is thus expected to maintain its confrontational stance towards the administration.

Whatever the outcome of the next two elections, modern history will remain as a key cleavage issue in Korea, where the Cold War rages on indefinitely. Yet the persistence of this irreconcilable split may come at the cost of neglect towards more salient economic and social issues that plague Korean society.

Kyu Seok Shim is an M.A. Candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).