In an op-ed for Times Higher Education last week, Imperial College London President Alice Gast proudly proclaimed U.K. universities to be “China’s best partners in the West.” Though largely a rhetorical reference to the strategic choice made by her nation’s leaders to become China’s best friend, Gast’s statement hits the nail on the head when it comes to China’s current soft power development in the U.K.

One of the greatest tools in China’s $10 billion-per year arsenal for external propaganda is education. Abroad, this manifests largely in Confucius Institutes, state-sponsored centers tasked with teaching Chinese culture and language. With over 480 centers operating in 120 countries, these Confucius Institutes have widespread global brand recognition.

The past two years, however, have seen increasing backlash against these institutes worldwide in light of accusations that the institutes fail to follow basic rules of academic discourse. In December 2013, the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) called on all universities to cease hosting Confucius Institutes. In June last year, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) made a similar call for U.S. universities to either cancel or renegotiate agreements to reflect Western values. Most recently, in June this year Germany’s Stuttgart Media University and the University of Hohenheim jointly cancelled their plan to open an institute after pressures from activist groups. Similar stories reverberate across Sweden, France, and Japan.

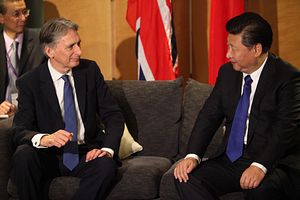

But unlike its Western counterparts, Britain shows no signs of abandoning its Confucius Institutes. Despite pressure from activist groups, the status of the institutes in the U.K. seems to be flourishing. As one of the last items on his itinerary in the U.K. last week, Chinese President Xi Jinping attended the opening ceremony of the annual conference of U.K. Confucius Institutes and Classrooms in London. Jointly with the Duke of York Prince Andrew, Xi formally opened the 1,000th Confucius classroom and gave a speech highlighting the rapid development that Confucius Institutes have enjoyed in the U.K. in recent years.

So far, with its 29 Confucius Institutes and 126 Confucius Classrooms, the U.K. ranks first among European countries in welcoming the Chinese influence, a fact that brings China’s state broadcaster to proclaim a “Confucius revival underway!”

Confucius Institutes are only one part of the picture. According to 2014 estimates, there are currently over around 150,000 Chinese students studying at U.K. institutions. As with its counterparts in North America and Europe, Britain’s institutions engage in countless partnerships with Chinese universities. Mutual understanding on education styles was recently popularized through a BBC program that brought five Chinese teachers into a British secondary school to test out the Chinese style of teaching in a British setting.

The U.K. stands out in its warming up to China — and there is enthusiasm at all levels. After his state visit to China in 2013, British Prime Minister David Cameron urged Britons to look beyond the traditional German and French language classes to focus instead on Mandarin. On a more organic level, in a 2014 survey conducted by Pew, the U.K. was the only European Union nation polled in which opinions about China are on balance favorable.

As Britain shifts closer to a pragmatic, consensus-driven approach with China, we will soon see more invigorated Chinese efforts in cultural infrastructure development in the U.K. Soft power, as the experts say, works best when complemented with sustained economic investment. China has already chosen Britain as the centerpiece for its RMB internationalization plan in Europe and the two sides have made plans to further discuss the “China-U.K. infrastructure alliance” in light of China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative.

The prevailing wisdom is that China’s soft power will always hit a brick wall. Problems like aggressive nationalism in South China Sea territorial disputes and failure to liberalize domestically pose threats to China’s perceived legitimacy and popularity abroad. But so far, that hasn’t put a damper on China’s educational outreach in the U.K. Whether or not China’s soft power project leads to any concrete benefits for the Middle Kingdom, Britain is eagerly poised to make manifest the “chemical reaction” that Xi says characterizes the cultural relations between the two nations.