Russia has been stepping up its submarine patrols near remote locations of fiber optic cables laid on the ocean floor and carrying digital data across continents the New York Times reports.

Pentagon officials and European diplomats speaking on the condition of anonymity compared Russian activities to Cold War levels, when both East and West repeatedly tried to tap undersea cables to extrapolate intelligence, something that is still standard practice among the world’s leading intelligence agencies, although it is rarely talked about in public.

The United States is in particular concerned about Russia’s burgeoning capabilities to interrupt global internet traffic communications by cutting undersea cables in the event of a conflict with the West. Russian submarine patrols have risen by over 50 percent in the last year, according to statements made by senior officials of the Russian Navy.

However, the precise nature of Russian activities remains highly classified. “It would be a concern to hear any country was tampering with communication cables; however, due to the classified nature of submarine operations, we do not discuss specifics,” a U.S. Navy spokesman told the New York Times.

It is also an open secret that the United States, given its technological superiority over peer competitors and the size of its navy, has been the most active in tapping undersea cables across the world oceans and collecting intelligence.

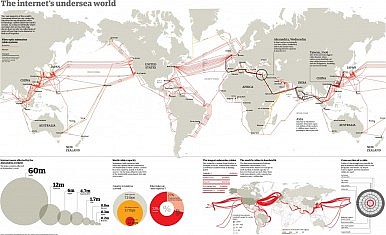

As I noted in 2010, most people are not aware that our global digital connectivity rests upon a number of fiber optic cables lying at the bottom of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. They wrongly believe that their international communications are carried via satellite links. The truth is that 99 percent of transcontinental Internet traffic travels through these connecting cables; these are the lifelines of our economies.

As I stated in my 2010 analysis:

Most of the cable cuts occur because of ship anchors, natural disasters such as earthquakes or fishing nets. While the technical reliability of these cables is very high, international politics have created three particular problem zones in the world – three cable chokepoints where undersea cables converge and where if cut, outages could have severe consequences. The first is in the Luzon Strait, the second in the Suez Canal-Red Sea-Mandab Strait passage, and the third is in the Strait of Malacca.

One can assume that any of these three chokepoints are closely being monitored by U.S. naval and spy assets and are also of great interest to the Chinese and Russian navies. Russia, however, given that the impact of cable cuts is felt across the world (see here), would potentially hurt its own economy by cutting cables in the event of a conflict.

Consequently, rather than Russia’s alleged new aggressiveness in targeting undersea cables, the real issue when it comes to a cable cuts at one of the chokepoints (and they occur quite frequently) is the repair time.

Depending on how quickly the cable system owner, the operator of the repair vessel, and the national government involved in coordinating their efforts can react, the loss of connectivity might last from a few days to a few weeks. A few countries – such as China and India–are notorious for delaying repair permits if the cuts appear in their territorial waters – this is the real danger to the world economy.

In 2012, I co-authored a study (See: “India’s Critical Role in the Resilience of the Global Undersea Communications Cable Infrastructure”) on how India, through the adaptation of best practices could vastly improve the cable repair times and as a consequence improve its international connectivity.

I repeatedly have argued in the past, that rather than seeing it as an additional hindrance to improving relations between the world’s great powers, the growing vulnerability of, and at the same time increased dependency on, undersea cables should be used as an opportunity for “undersea cable diplomacy” to bring potential adversaries together.

It is in the interest of the United States and Russia that cable repair times across the world are sped up, and while tapping undersea cables for intelligence purposes will remain standard practice among most countries with the capability of doing so, the real threat to global connectivity is not so much another nation’s navy but more often the bureaucratic red tape in one’s own country.