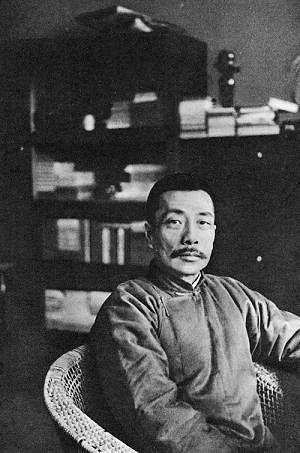

Undoubtedly, in the 20th century Lu Xun (1881-1936) and Hu Shih (1891-1962) were two giants in the field of Chinese culture and public knowledge. These two public intellectuals had the deepest influence upon China’s cultural sphere, and even the political sphere. But over the past few decades, especially recently, there’s been an increasing tendency to set these two giants against each other. These two are constantly set up as opponents. People following them choose different roads, and the two men themselves were estranged during their lifetimes.

Yet my own view is this: ultimately they are two sides of the same coin; not only complementary, but indispensable.

Lu Xun is the shot fired into the darkness, who abhors wickedness and fought it to the end while advocating for “no tolerance.” Meanwhile Hu Shih is Prometheus introducing the light to the world, accepting good advice, and advocating that “tolerance is more important than freedom.” After resigning from the Ministry of Education in disgust, Lu Xun kept his distance from the halls of power and remained a poor writer until his death, while Hu Shih cooperated with the powers-that-be from the beginning, taking positions in the government of the dictator Chiang Kai-shek, whom Hu had criticized. Hu even became China’s ambassador to the U.S.

Undoubtedly, Lu Xun is seen as “left-leaning” in the modern political view and was long praised by Mao Zedong. However, Mao himself also said, “If he [Lu] were still alive today, he would have either shut up or gone to prison.” More importantly, the darkness Lu exposed is still hanging over his country, even though the “leftists” prevailed in the end. The fact that Lu Xun is still an “unbeatable giant” (as Cao Chanqing called him) marks Lu’s great mastery of literature and ideology, but it’s tragedy for the nation and the state. The darkness which Lu tried to remove still remains, and has even grown denser. Lu only created one “Ah Q,” the character famous for both his weakness and his inability to recognize his own sorry state. But now, there are so many “Ah Qs” that we could make an “Ah Q Republic.”

On the other hand, Hu Shih has become more and more successful. His thoughts have been raised to an untouchable status by academics; the development of the state and nation gave him a status he could never have reached on his own. The reason is that the “light” which he tried to introduce during his lifetime has finally illuminated part of China. His thoughts became political practice: Taiwan achieved the gradual transformation of the Kuomintang regime while avoiding extreme social upheaval.

This is the reason for an increasingly fierce rethinking of Lu Xun while coming to a new appreciation of Hu Shih. Most intellectuals judge a hero by his successes and failures, and the darkness disclosed by Lu Xun remains unchanged, while the light introduced by Hu Shih shines on the earth today.

I was deeply influenced by Lu Xun, and have read almost all of his articles more than once. At least half of my articles are influenced by him and stamped with his brand. Many readers see that these articles have a “Lu Xun style,” and these are also the most popular parts among readers. Conversely, I’ve barely read any articles by Hu Shih, but in the end I’ve come to agree more with his words, style, concepts, and way of behavior. This sounds somewhat strange, so I have to explain.

I received a traditional education on mainland China, and grew up together with Lu Xun’s books. Later, I studied international politics, but mostly only read the books of Marx and foreign political scholars. So I hadn’t read any articles by Hu Shih by the time I went abroad in the 1990s. But during the ten years I was abroad, I read almost all of those original works by foreign scholars that influenced Hu Shih (mostly, I confess, because I was bored and had nothing else to read). After Hu became more popular, I found that almost all of his ideas could be found in important works from Western scholars — and these works were more thorough, and indeed classics. Therefore, though I agree with Hu Shih’s thoughts, I haven’t found any surprises or extra benefits from reading his articles.

However, it is different when I read the articles of Lu Xun. Over many years, I’ve read a lot of foreign literature, commentaries, and essays, and seen much criticism that Lu “only knows how to criticize.” But I have to admit that Lu is one of a kind — and he is China’s! Lu Xun’s diagnosis of China’s darkness is unsurpassable, even today, while Hu Shih’s most brilliant thoughts are “copied” from classic Western works. Here, I have to stress that I prefer Hu’s moderate rationality and reformist thoughts. However, if there is no Lu Xun thought, the spark which can ignite the revolution, reforms will have no power.

I hopelessly hover between Lu Xun and Hu Shih. I am influenced by both Lu Xun who argues for “no tolerance” and Hu Shih who sticks to both tolerance and compromise. From my motto of “hating wickedness and accepting good advice,” you can see my irreversible ambivalence. It’s a good slogan, but how many people can really do both those things?

In his later years, Lu tried to get rid of his satirical style. He cut down on his acrimony and “stubbornness,” and even began to write about heroes in order to bring positive energy to society. Too bad few people read those works. Even worse, Lu died early — but maybe dying before 1949 and failing to see today’s China is the reason he had the good luck to become a literary and intellectual giant?

Hu Shih’s situation was just as difficult. As someone who accepted money and help from Chiang Kai-shek, Hu Shih had to try to influence the authorities to make the right policy adjustments while working under strict limitations. He not only had to be very careful when speaking out against wrongdoing, but most of the time was rubbing elbows with the wrongdoers. While Hu Shih held different posts in the Republic of China, the Chiang Kai-shek regime violated human rights, suppressed dissent, and crushed democracy advocates. But this didn’t weaken the respectability of Hu Shih as a cultural and ideological giant.

Both Lu Xun and Hu Shih are needed today. The purpose of piercing the darkness is to introduce the light, and hating wickedness is only way you can accept good advice. It’s too extreme to suppress Hu Shih with Lu Xun or to belittle Lu Xun by praising Hu Shih.

However, the saddest thing is that, thanks to the suppression and control of speech, we have lost those like Lu Xun, people who expose the darkness. And thanks to the shortsightedness of interest groups, we can’t see what positive roles are being played by modern-day Hu Shihs. In a time without either Lu Xun or Hu Shih, we can only look back on our cultural giants and on the difficult fate of the state and the nation.

This piece originally appeared in Chinese on Yang Hengjun’s blog. The original post can be found here.