On October 13, Okinawan Governor Takeshi Onaga made good on a longstanding threat to rescind prefectural approval for the land reclamation efforts necessary to building the Futenma Replacement Facility in Henoko. It was the latest move in the drawn-out battle over Futenma Marine Air Station, called the “most dangerous air station in the world” due to its location in a densely populated urban area.

A deal to return Futenma to Okinawan control was first announced in 1996. But nearly 20 years later, that promise still has not been realized. That’s because the issue of U.S. bases on Okinawa is bigger than the specific question of Futenma. It touches on deeply-held emotions, historical memory, and calculations regarding national security and political machinations.

The Futenma Issue

One of the oddities in the Futenma question is that all parties involved – the U.S. government, the central Japanese government, and the Okinawan prefectural government – agree that the Futenma air station has got to go. The Marine Corps Air Station Futenma (as it is formally known) is surrounded by residential areas, schools, and city buildings. According to former Okinawan Governor Masahide Ota, there are 16 schools, hospitals, and city offices in the immediate area, plus 3,000 people living in what should be the “clear zone” around the base.

The debate is over the actual relocation – that is, should Futenma be relocated at all, or simply shut down? And if it is to be relocated, where will the replacement be built?

The official plan calls for a Futenma Replacement Facility (FRF) to be built in Henoko, close to the Camp Schwab Marine Corps Base. The new air station would have two 1,200 meter runways arranged in a V-shape, mostly built on reclaimed land (the same land reclamation for which Onaga just withdrew prefectural approval).

Okinawan residents, however, are overwhelmingly against the relocation of Futenma to Henoko, with 83 percent of Okinawans opposing the plan, according to one local newspaper poll. Okinawans believe they already bear too much of the burden for the U.S. military presence in Japan. The oft-quoted statistic: the island of Okinawa represents just 0.6 percent of Japan’s territory but hosts 74 percent of U.S. military installations in Japan.

Okinawa’s US Bases: “It’s Really Outrageous”

Okinawans object to the number of bases on their island for many reasons, some obvious and some less so. The obvious reasons are the disruptions U.S. military installations (and particularly airfields) cause to daily life: noise pollution, accidents and environmental damage, and violent incidents including rapes and brawls involving U.S. military personnel.

Kiku Nakayama, a survivor of the Battle of Okinawa who devotes much of her time to anti-base activism, comes prepared for our meeting: she’s carrying a stack of newspapers around an inch thick. Each one contains a story tied to some negative incident involving U.S. military installations: Ospreys flying overheard in the middle of the night and keeping residents awake; universities and schools protesting U.S. military flights during school hours; a brawl involving U.S. soldiers. These reports, she says, are just from the last three weeks.

It’s “really outrageous” how many bases are in Okinawa, Nakayama says.

Another Okinawan, local radio company chairman Takemasa Ishikawa, says that human rights are being infringed upon thanks to the bases. There are so many accidents, incidents and crimes, he says, that the bases truly bring suffering to the Okinawan people.

Okinawans also complain that the vast number of bases has crippled the island’s economic growth. Nearly 20 percent of the total land area of Okinawa Island is taken up by U.S. bases – land that could otherwise be occupied by houses, hotels, restaurants, and businesses. Ishikawa says that the U.S. base factor is one of the main reasons Okinawa has the lowest income level of any prefecture in Japan. Of course, bases provide employment opportunities as well, but critics say they are a net negative for Okinawa’s economy.

But the base issue goes beyond the tangible impact of the bases. More than anything else, it’s the attitude of the Japanese central government toward the issue that irks Okinawans. There are profound feelings of alienation on the island; over and over again I hear that Okinawa is being discriminated against by mainland Japan.

The historical roots of that sentiment run deep. Okinawa was home to the independent Ryukyu kingdom until it was subsumed by Japan in 1879. Then, in 1945, the island was the site of the only land battle in Japan during World War II. The local perception is that Okinawan people and homes were sacrificed in the Battle of Okinawa to buy time for mainland Japan to shore up its defense. Over 94,000 Okinawans civilians died in the taking of Okinawa; the Okinawan Prefectural Peace Museum heavily implies they were needlessly sacrificed as part of Tokyo’s “war of attrition” strategy.

Today, Okinawans believe their island and their lives are still being sacrificed to serve mainland Japan (and, of course, the United States). Many of them readily admit to the security value of the U.S.-Japan alliance and even the installation of U.S. bases in Japan. They just don’t understand why their island bears so much of the burden.

Ota points to these historical issues as a major cause of the tensions today. Without the experience of the Battle of Okinawa perhaps the Okinawan people would be more receptive to hosting military facilities. “Okinawa shouldn’t be a battlefield again, so that’s why Okinawan people reject military bases,” he explains.

Plus, if the bases are so important to Japan’s national security, why is it that no other prefecture will accept them – and that Okinawa is stuck with them instead? The answer is that the “Japanese government does not pay any attention to the sufferings of Okinawan people,” Ota argues.

Nakayama, along with many of my other interviewees, agrees that Okinawans are being discriminated against. It doesn’t matter if the bases are located in Okinawa or elsewhere, she says, and it’s “not right” that the central government is ignoring the wishes of the Okinawan people when it comes to the Futenma relocation. Japan and the United States are both democracies, she says, but their approach to Okinawa “is not democratic at all.”

Kurayoshi Takara, who served as vice governor of Okinawa under Hirokazu Nakaima, Onaga’s predecessor, says that the Okinawa people “are always victims.” Japan “sacrificed Okinawa to the U.S.” when Tokyo lost the war, he says, and since then nothing has substantially changed: Okinawa is still largely alone in bearing the burden of the U.S.-Japan security alliance.

Okinawa: The “Keystone of the Pacific”

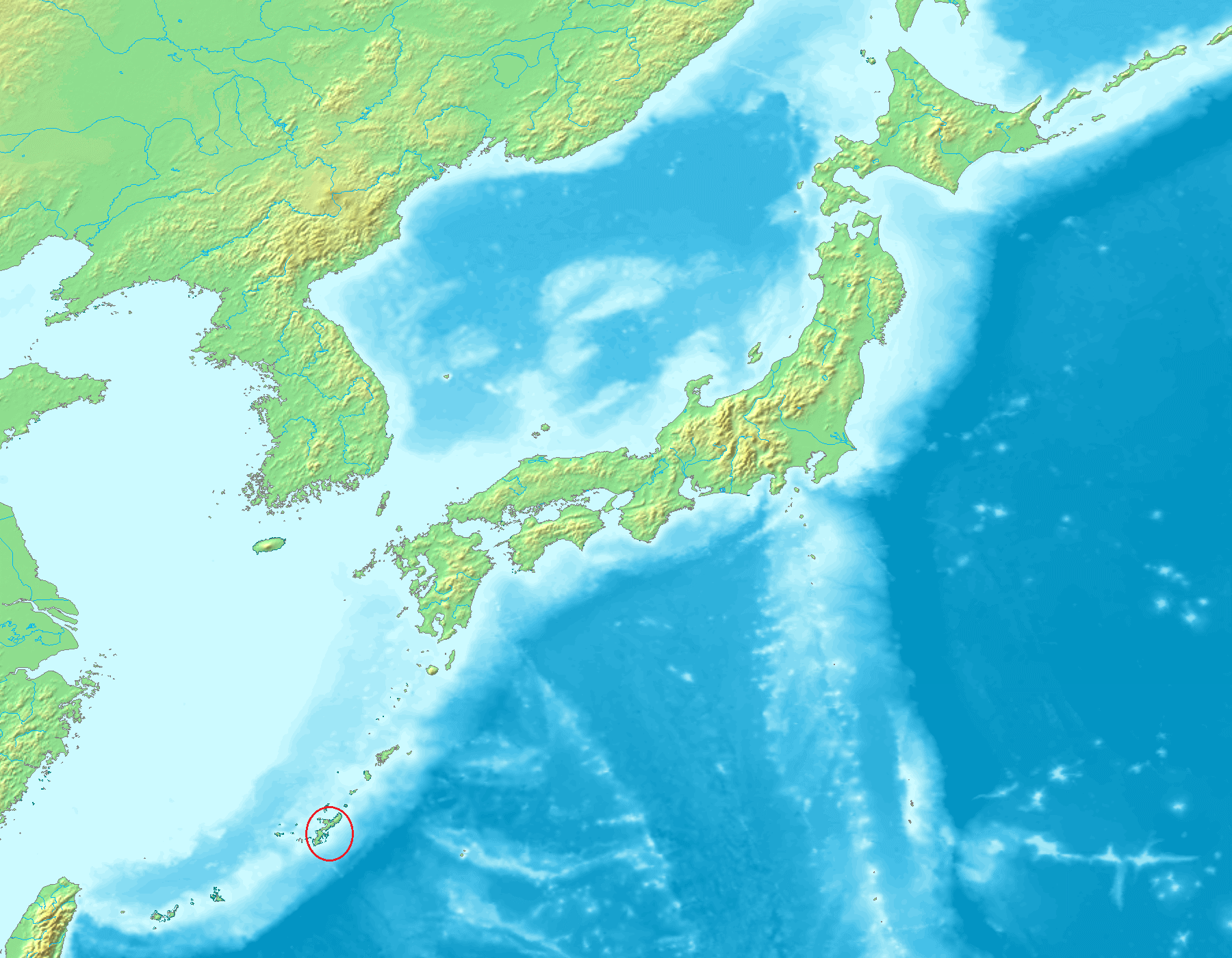

In Tokyo, ask a security specialist why Okinawa is home to so many U.S. military bases, and you get a clear answer that has nothing to do with complex historical issues. In fact, former defense minister Satoshi Morimoto simply pulls out a map to demonstrate:

It is 1,100 kilometers from Kyushu (the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands) to the southern islands, Morimoto explains. This is China’s only good route to the open ocean beyond the first island chain. Japan is intensifying its own SDF presence around these islands, he says, and it’s also “very crucial” to keep U.S. forces stationed on Okinawa.

As for the relocation of Futenma to Henoko, the central government has a “very strong determination to implement this construction project at any cost,” Morimoto says. His message to America on this question: “Don’t worry.”

Tomohiko Taniguchi, a professor at Keio University Graduate School and a special adviser to Shinzo Abe’s Cabinet, describes Okinawa along similar lines. “Given the expansionist policy Beijing is after over the maritime domain, Okinawa and the strategic value the island chain holds have never been as high as they are now,” Taniguchi says. Japan’s location – and particularly Okinawa’s geographic position – is precisely why the United States considers Japan such an important ally.

There’s a reason the United States has long referred to Okinawa as the “Keystone of the Pacific.” Given Okinawa’s strategic location and growing security concerns vis-à-vis China, officials in Tokyo are not willing to simply shutter Futenma, thereby reducing the U.S. military presence on the island. Koji Kano, the director of defense policy in Japan’s Ministry of Defense, says that Japan “cannot afford to decrease the deterrent or response capability of the [U.S.-Japan] alliance.” The security environment is “dire” – particularly when it comes to Japan’s southwestern islands. “Just throwing away that air station is not a good idea, and [is] something we cannot afford,” he argues.

The relocation of the base is vital, Kano explains, as keeping the base where it is now is too dangerous. The relocation to Henoko is important for the U.S.-Japan alliance, Japan’s security policy, and for reducing the risks associated with the Futenma base. Completing the relocation is the “only viable way,” Kano says. “There is no Plan B.”

“Making an Excuse”

Back in Okinawa, explanations of deterrence and geostrategic locations fall flat. Asked about Tokyo’s explanation for why Okinawa hosts the vast majority of U.S. bases in Japan, Ota says flatly that “the Japanese government is making an excuse.” He explains that during his administration, he had many meetings with U.S. officials about the possibility of relocating bases to Guam or elsewhere in Japan. People in Washington seemed sympathetic, but Tokyo was not, according to Ota.

For Okinawans, the everyday reality of living with U.S. bases resonates more with the general public than abstract security concerns. Japanese analysts describe the security situation as getting worse nearly by the day, but Takara explains that people in Okinawa don’t see that in their daily lives: “They do not really feel that the dangers are increasing.” And while the majority of Okinawans would agree that the U.S.-Japan alliance is important, he says, that doesn’t equate to a willingness to give up their land for U.S. bases. That’s why many Okinawans don’t like being asked such questions, he explains – it’s hard to convey an understanding of the importance of the alliance while also being clear about not wanting U.S. bases on Okinawan soil.

Former LDP secretary-general Shigeru Ishiba (who currently serves as minister for regional revitalization) acknowledges that there need to be more efforts from Tokyo to take into account the feelings in Okinawa. Mainland Japan “must never forget” that Okinawa was the only site of a ground battle on Japanese soil during World War II, with all the attending emotions that stirred up, Ishiba says.

Kano, meanwhile, is fully aware of the feelings on Okinawa. There are “lots of concerns” about the Futenma relocation plan, but the Ministry of Defense believes moving the air station to Henoko “is the most important and right thing,” as does Kano personally. He hopes those who are against the relocation will eventually realize that it’s the only way Japan can provide for the security of all its citizens. It is “demanding and daunting” to get the local community to agree, but “we have to do it” for the sake of Okinawan people and for the sake of deterrence, he says.

“I’m not ashamed of myself if we assert [ourselves] on this,” Kano finishes. “I can tell it to the Okinawan people directly, even though they yell at me.”

But what the Okinawan people want most of all is not to be told but to be asked what will happen on their island. If national security concerns mean that Henoko is truly the only place where Japan and the United States can put the new base, “I want to hear them say so,” says local radio chairman Ishikawa. And, more importantly, he wants to hear Tokyo and Washington ask Okinawans if they are willing to make the sacrifices required to continue hosting U.S. bases. That sort of equality, he says, is all Okinawans have ever wanted: “Treat us as the same human beings as you.”