What has been largely overlooked in the conversation to date around China’s campaign of dredging and construction in the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea is the necessary synthesis between the geopolitical and environmental aspects of the issue.

In recent months, U.S. Navy patrols in the South China Sea and denouncements from high-ranking U.S. officials have brought international attention to the troubling security implications of China’s actions.

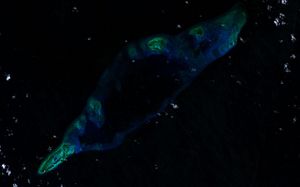

A secondary line of reporting across the English-speaking world has also emphasized the ecological damage this artificial island-building is causing to a large system of coral reefs, with high-resolution satellite data illustrating the extent and pace of the damage.

With regard to these two lines of analysis–security and ecology–the conversation to date about the Spratly Islands has been notably and regrettably stove-piped.

To be clear, China’s actions constitute a violation of international law, a potential precursor to interference in one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, and a catalyst for military confrontation in the region.

The worst case scenario—wherein the People’s Liberation Army Navy is able to “lock down” the South China Sea and prevent freedom of navigation by, say, a U.S. Navy carrier strike group or liquefied natural gas tankers headed for Japan—is worrisome on multiple levels.

But geopolitical concerns actually go hand-in-hand with ecological concerns.

A Link in the Food Chain

The Spratly Islands’ coral reefs serve as spawning grounds and nurseries for nearly 400 fish species, including various commercially important stocks.

By smothering and destroying these reefs, China’s actions will be detrimental to coastal populations as far away as the Philippines, Malaysia, and Vietnam that depend on these living marine resources as a major source of daily protein and household income.

The government of the Philippines estimates that the Spratly Islands reefs support roughly “$100 million in high value fisheries.” Across the region as a whole, the figure is likely a multiple of that.

Destroying ecosystems and eroding food security is problematic in and of itself. But, as witnessed in conflict zones around the world, depleting natural resources also multiplies the threat of violent extremism, organized crime, and infectious disease—threats that should matter even to policymakers with little sympathy for the environmental agenda.

The Security Nexus

Environmental degradation deprives communities in developing countries of their traditional livelihoods. In turn, this can produce a generation of disaffected young men primed for recruitment by armed, non-state groups.

Many of the humanitarian crises and outbreaks of violent extremism which have consumed the attention of Western governments in recent years have, in hindsight, had a distinctly environmental dimension. Somalia and Syria are two examples of note.

In Somalia, the link between overfishing by unscrupulous foreign fleets and the rise of piracy targeting international shipping has been well-documented (PDF). And the problem could rear its head again, as the naval task force which so effectively tamped down the pirates did nothing to address the root cause of their criminality.

Likewise, while it is impossible to attribute the civil war in Syria to a single factor, researchers now suggest that natural resource conflicts played a key role. Specifically, severe drought and poor management of water resources increased tensions, drove farmers and their families into overcrowded urban centers, and heightened existing grievances with the Assad regime.

In both these cases, natural resource scarcities brought about by ill-considered development and lack of governance directly fueled the rise of violent extremism.

Even in the absence of armed militias, environmental degradation can have disturbing implications for human security. Multiple studies indicate that rapid deforestation combined with urbanization in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone may have sparked last year’s deadly Ebola outbreak by bringing ever larger numbers of people into contact with disease vectors, namely infected bats.

Changing Sea State

To what degree the militarization of the South China Sea islands could destabilize the larger region remains a topic for speculation.

But examples (PDF) from across Asia illustrate that degraded ecosystems and depleted fish stocks drive some actors to disregard legal or customary frameworks of fisheries management and engage in illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Regional analysts note that the IUU business model often goes hand-in-hand with piracy, human trafficking, and smuggling of arms and drugs (paywall).

Unfortunately, last year the U.S. Navy disbanded its nascent Maritime Civil Affairs and Security Training Command, one of the more promising American initiatives to combat organized crime in developing coastal states, citing budget concerns. While the Navy pledged to redistribute the command’s responsibilities to other forces, the lack of a dedicated unit sends a clear signal that the U.S. does not consider the use of soft-power and capacity-building around these issues a priority.

Western governments and intergovernmental organizations are likely to recycle reactive responses to these complex and multifaceted challenges unless they work to fuse intelligence across knowledge communities and address root causes.

Assessing environmental and security threats as unrelated issues reflects an outdated worldview and leaves the U.S. and its allies vulnerable to unforeseen outcomes.

In today’s world, ecological crises are security threats. This is doubly true in the South China Sea.

Matthew Nichols holds an M.A. in International Environmental Policy from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and has worked as a researcher and consultant with clients including Maersk Group, the U.S. Navy, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The views expressed in this paper are entirely the author’s own.