Luc Forsyth and Gareth Bright have set out on a journey to follow the Mekong river from sea to source. The Diplomat will be sharing some of the stories they’ve found along the way. For more about the project, check out the whole series here.

As we leave the border towns of eastern Cambodia behind for the nation’s capital, we stop to visit old friends and get an intensely personal history lesson we never expected.

* * *

Even after seven months of regular contact, it was hard to know how Yu Sos felt about us. A short, swarthy man with a wiry neck beard, he was not prone to outbursts of cheer; I could count the number of times I had seen him smile using my fingers alone, and I had never seen him laugh. When Gareth and I first met him we initially assumed he didn’t like us, but over the course of our relationship he had repeatedly demonstrated exceptional generosity and patience, furthering our confusion about the paradox between his actions and his outward mood. For more than half a year we looked forward to our visits to his family’s house boat at the confluence of the Mekong and Cambodia’s Tonle Sap river in Phnom Penh, while simultaneously fearing that he secretly hated us. It wasn’t until “A River’s Tail” gave us a budget to employ a dedicated translator that we were able to finally penetrate his mask of stoicism and fully understand the precarious situation of the river-dwelling Cham community that he oversaw.

Mat Salas, 57, sits on his fishing boat as his daughter stands behind. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Chams, as the ethnic group which inhabits parts of Cambodia and southern Vietnam are known, represent the last vestiges of a defeated empire. A major power in what is now south and central Vietnam for more than a thousand years, the Kingdom of Champa was fully annexed by the Vietnamese in the 1800s. At odds with the predominantly Buddhist states of Southeast Asia, Champa was heavily influenced by both Hinduism and Islam, and the modern day Chams remain divided between the two faiths to this day. The majority of Vietnamese Chams practice Hinduism, while those in Cambodia are overwhelmingly Muslim.

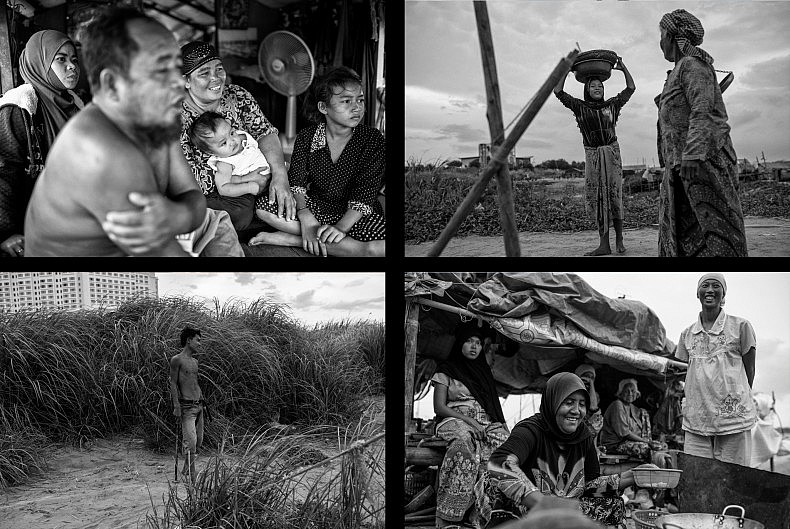

Photos by Gareth Bright.

As we entered the Cham community on the southern tip of Phnom Penh’s Chroy Changvar peninsula and made our way to Yu Sos’ home, we were greeted with assalamu alaikum rather than the normal sues-dei uttered by Khmers — reminding us that while the residents might look no different than the rest of Cambodians, we were entering into a distinctly different culture.

Despite the fact that the vast majority of the community lived on houseboats rather than on land, over the following days that we spent with the Chams we learned that their relationship to water was far from harmonious.

Photos by Luc Forsyth.

Formation By Conflict

When Phnom Penh fell to the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime in 1975, Yu Sos decided to swim for freedom. Jumping into the Tonle Sap river at 3 am, he clutched a banana tree to stay afloat as he drifted with the current. “Some soldiers saw me and tried to shoot me,” Yu told us as we sat cross-legged in his floating home, miming the automatic firing of an AK-47 to illustrate his story, “but I dove under the water and [the bullets] missed.”

A woman in traditional dress prepares for afternoon prayer in the Phnom Penh’s biggest Cham Community. Photo by Gareth Bright.

For nearly two days he floated toward Vietnam until nearly drowning when the banana tree got caught in the net of a fishing trawler. The ship’s crew hauled the exhausted Yu onboard and turned him over to the Vietnamese military. After an intense interrogation session he was conscripted into the Vietnamese army and sent back to his home country to fight the regime he had been so intent on escaping.

A Cham man touches his head to the floor in prayer. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

After four years of gritty guerrilla warfare the Khmer Rouge were defeated and Yu was reunited with the family he had left behind.

“When I found my parents we cried together,” he remembered. In the aftermath of the four year conflict that left millions of Cambodians dead and its society in ruins, Yu and his family began the process of looking for a new home. The Khmer Rouge had stripped most Cambodians of their property titles as they redistributed land in their ruthless mission of creating their idealized vision of a communal agrarian society, and many, including Yu, did not know where they were and were not allowed to settle. After attempting to establish a life in the city of Prey Veng, their post-war poverty forced them to move on yet again.

Chams are ethnic Cambodian Muslims who typically work as fisherman and so often live along Cambodia’s waterways. Photo by Gareth Bright.

“We didn’t have any money to buy a house, so we got a boat and drove it to Phnom Penh,” Yu told us. “When we arrived we found other families [on boats] in the same situation as us, so we got permission to from the authorities to form a community together.”

Though Yu told us this story with a characteristic lack of emotion, both Gareth and I were stunned into silence for several minutes. The wooden fishing boat we had used for the three week trip into Cambodia’s Tonle Sap lake that gave rise to the “A River’s Tail project” was docked in the Cham community and looked after by Yu’s oldest son, and we had visited nearly a dozen times in the last year. Yet despite our numerous interactions (Yu and his son had painstakingly taught us to drive our vessel, never losing their calm despite our ineptitude), we had never learned this aspect of the community’s formation because of the language barrier between us. Had “A River’s Tail” not given us the means to return to the community with a translator we likely would have remained ignorant of the traumatic history.

Roughly 250 families inhabit this Cham village. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

In an hour of conversation our perceptions of Yu and the Chams had been forever altered; suddenly his gruff demeanor didn’t seem so hard to understand.

The Realities of the Voiceless

“No one wants to live on these boats,” Yu said matter-of-factly, shattering the last of our illusions about Phnom Penh’s Chams. Upon entering the village, which sat under the shadow of the newly completed Sokha Hotel, it was clear that the residents were not wealthy. Those who lived on the shore did so in hodgepodge shacks made of wood, thatch, plastic, and bits of tin, while the boats of those living offshore were aged and in varying stages of disrepair. Yet despite the obvious poverty, we hadn’t fully let go of the thought that perhaps the Chams didn’t need money to be happy, or that somehow their floating community derived its self-identity from the river and didn’t require the modern affectation of material possessions. Maybe, we thought, these people lived a quaint and simple life that the rest of the smart-phone obsessed world needed to learn from. Yu’s to-the-point synopsis quickly dispelled our naivety.

Yu Sos in stands in front of the newly erected Sokha Hotel. In Phnom Penh, a community of Chams live floating lives on boats and stilted houses, but the unprecedented pace of land development in Cambodia’s capital puts them under constant threat of eviction. Photo by Gareth Bright.

“I don’t really like the river much, but I have no choice.” Yu stated plainly. “When it storms we worry about our kids drowning, and they can’t go to school because we need them to help us fish. Many of us can’t afford to buy water, and so we drink it from the river, which makes us sick — I have problems with my kidneys because of it. We are trying to get a piece of land from the government so it is easier to manage these problems.”

A Cham girl stands on the shoreline, overlooking the floating community where she lives. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Yu went on to tell us that, if given the option, he would gladly accept an even less pay than he earns as an artisanal fisherman (a meager sum to begin with) for the chance to move his family off the river and onto land. His connection to the river is one of necessity, not choice: “I depend on fish from the river for my living just like a shopkeeper does his shop. But every year the amount of fish I can catch is going down.”

Photo by Gareth Bright.

As if these varied hardships weren’t enough, the community is in peril of losing what little they have — the narrow strip of land onto which they anchor their boats. Corporate developers, particularly the Sokimex Group, which owns the $100 million Sokha Hotel that dominates the skyline above the Cham village, apply constant pressure in their mission to have the community removed from their property.

“We had to move to this place after the hotel asked us to move from where we were before. They work with the authorities and the police came and told us they would sink our boats if we didn’t move,” Yu remembered. And while a tentative agreement was reached, allowing the Chams to stay in their current location, Yu fears that the agreement will be broken. “If that happens,” Yu said, “I don’t know where we can go.”

Photo by Luc Forsyth

After several days in the Cham community, our schedule dictated that we had to continue up the Tonle Sap to the riverside city of Kampong Chhnang and its surrounding villages. As we shook hands and wished Yu luck in securing a future for his village, a rare smile twitched at the corners of his mouth: “Wa-Alaikum-Salaam,” he said in farewell.

And upon you peace.

This piece originally appeared at A River’s Tail.