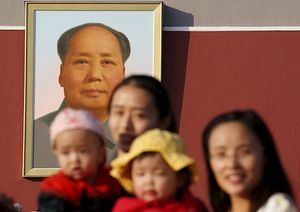

When the two-child policy, under which married Chinese couples can have two children was passed this past October, reactions were mixed. Some couples reacted with joy at the prospect of being able to have two children. Others criticized the two-child policy for not going far enough. Most were still confused by how exactly the sweeping policy change would be implemented. More than four months after the two-child policy was instituted, everyone is still wondering: Just how far reaching policy-wise will the effects of this new family planning policy be?

Besides having long-lasting effects on the very social fabric of Chinese society (China has one of the worst gender imbalances in the world, and children without siblings struggle to support their many aging relatives), the one-child policy will also be remembered for its economic legacy. Fewer and fewer younger workers have replaced rapidly aging ones, and the strain on China’s once-cheap labor pool is now showing.

Much of the ambiguity surrounding the two-child policy has to do with the way it is being implemented. While the policy itself was passed by a national body – the National People’s Congress’ Standing Committee, delegated with administering to the nation’s laws – the creation and implementation of actionable guidelines has been left to the provinces. The diffusion of responsibility has led to a marked lack of action around creating new programs to encourage more births in China.

Moreover, few people have openly discussed what social scientists and policy analysts have been writing about for decades: No one quite knows how to reliably boost birthrates. Countries like Japan and Russia, which have experienced steadily declining populations for years, have only seen marginal birth rate increases despite having much more robust material incentives in place to encourage multiple births per family. Evidence suggests that countries that experience low fertility rates develop self-reinforcing mechanisms for maintaining low birth rates. The “stickiness” of low birth rates may be much resilient than China anticipated.

Twelve Chinese provinces have taken steps towards changing maternal and marital leave regulations to encourage more births. Once encouraged, late marriage (defined as marriage after the age of 25 for women and after 27 for men) will no longer be rewarded with an extra holiday, as it was previously. The rule changes came into effect January 1, 2016, and many couples in mainland China rushed to take advantage of the late marriage leave before the new year. Shanxi province even increased its marriage leave to thirty days, ostensibly to encourage couples to marry early. Most other provinces offer marriage leaves of three days. Provinces also extended maternity and nursing leave policies. Tianjin has the shortest maternal leave at 128 days while Fujian province gives its female residents up to 180 days of maternity leave.

Whether such changes will have lasting effects remains to be seen. Maternity leave extensions and other policies aimed at making it easier for working women to re-enter the workforce after having children have produced mixed results in countries like Japan and Sweden,

Policies to promote gender equality and support non-marital births have had better luck achieving tangible results in the Scandinavian and European countries, but these policies are unlikely to be adopted by China. “I suspect there will be a bit of a backlash against the gains made by women, similar to the backlash in U.S. post world war when men returned from war and there was pushback for women to resume maternal, homemaker roles,” says Mei Fong, a journalist whose forthcoming book One Child draws from her extensive reporting on the policy. In China, couples who give birth out of wedlock are still fined and their children denied hukou, making them ineligible to access basic social services such as public education.

However, the greatest obstacle to creating programs and provincial laws to implement the two-child policy is economic inequality. The brunt of the demographic imbalance has been dealt unequally among China’s provinces. Cities like Shanghai and Beijing attract millions of transplants and migrant workers each year and have been cushioned from the effects of the labor shortage. Higher living costs and better social welfare systems (for those who have urban hukou, at least) have caused many of China’s urban middle class to voluntarily forgo having more than one child. Meanwhile, couples in areas like Anhui or Shandong who supply much of the labor that powers China’s labor-intensive industries are more likely to have more than one child – but gauging exactly how much material support and through what channels that support should be offered is unclear. The cost of having a second child can be so prohibitive that some couples who would otherwise want to raise two children may not be able to afford to.

As a result, the provinces have tiptoed around how to implement the two-child policy. “No one wants to make the first move in case they cause unintended consequences in the future,” says Kuangshi Huang, an associate professor at the China Population and Development Research Center. Sichuan and Zhejiang have kicked off general county-level training for healthcare and government workers on the two-child policy to ensure that the new guidelines are widely circulated and to encourage hospitals to prepare themselves to handle more births. However, more detailed programs have yet to emerge.

The lack of accurate population statistics will likely prolong the ambiguity surrounding the two-child policy. Unable to pay the fines or unwilling to undergo a forced abortion, many parents in the one-child days gave birth in secret. These “black children” remained undocumented – and thus are not reflected in current population statistics. A large portion of these undocumented children are also females, the result of families who were unwilling to fill their one child quota before they had a boy. China’s “floating population” of nearly 170 million migrant workers make tallying exact population numbers even more difficult within provinces. Designing policy without an accurate picture of the demographic conditions will likely prove a tricky proposition.

What is missing are targets for birth quotas that each province should be aiming for, says Huang of the Population and Development Research Center. “There is no truly scientific understanding yet of exactly to what level the population is decreasing and thus no exact numbers for how many births we need to add,” said Huang. China has set its annual birthrate target at 20 million live births, and the National Health and Family Planning Commission announced it expected the two-child policy to boost birth rates by three million additional births a year. However, these numbers are not based on specific calculations but are rough estimates, says Huang.

In the absence of any concrete information about how to pursue the targets laid out in the two-child policy, what we can be sure about is that the results of social engineering of any sort – especially on the scale China is attempting – is unpredictable at best.

Emily Feng is a reporting intern at the Beijing bureau of The New York Times where she covers politics and society. Previously, she researched urbanization in East and Southeast Asia with a focus on migrant education and migration in China.