Japanese policymakers expressed diplomatic interest in the Arctic – a region rapidly being transformed by climate change –as early as 2009, when the country officially submitted an application to become a Permanent Observer in the Arctic Council.

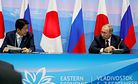

Japan’s bid (supported by, surprise, Russia), was approved in May 2013, along with China and South Korea’s. This instance of Russo-Japanese cooperation, particularly notable because Russia did not show such support for China, foreshadows the ways in which Japan will continue to try to leverage its ties with Russia in the Arctic. Japan benefits from cooperating with Russia because doing so will increase resource-poor Japan’s access to energy resources in and sea routes through the region.

Japan did not really have a comprehensive strategy with regard to the Arctic until October 2015. Even then, the “strategy” reads more like a laundry list of issues Japan had an interest in – global environment issues, indigenous peoples of the Arctic, science and technology, ensuring rule of law and international cooperation, the Arctic Sea Route, natural resources development, and national security – rather than a grand vision that outlines what Japan’s priorities are.

However, Japan’s Arctic strategy gained sharper focus with Kazuko Shiraishi‘s press conference in Moscow on February 29. Shiraishi is Japan’s special ambassador in charge of Arctic affairs. According to Shiraishi, the three main areas of Russo-Japanese cooperation in the Arctic include: research, the Northern Sea Route, and the Yamal liquefied natural gas (LNG) project.

The Northern Sea Route (also known as the Northeast Passage) is important to Japan’s strategic thinking because it is the shortest route from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The Northern Sea Route, traversing along the northern coast of Siberia, cuts travel time from China to Europe by at least 12 days compared to the Suez route. It can be an alternative way for Japan to transport energy resources from the Middle East, reducing reliance on crowded and narrow routes such as the Strait of Hormuz and the Strait of Malacca.

Last June, Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed an order to increase the Northern Sea Route’s capacity from the current 4 million tons to 80 million tons in the next 15 years. Japan would definitely benefit from such a development.

Japan is also trying to get involved with Russia’s $27 billion Yamal LNG project, one of the largest industrial projects in the Russian Arctic. Novatek, Russia’s largest independent natural gas producer, owns 60 percent share in the project, France’s Total 20 percent, and China’s China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) 20 percent. Novatek chief executive Leonid Mikhelson told TASS, “We would welcome Japanese companies participating in this project as investors and as engineering companies and as suppliers.” Scheduled to start operations in 2017, the project is expected to have an annual capacity of 16.5 million metric tons of gas. The Yamal LNG project will extract gas from Yuzhno-Tambeysk natural gas field, which has estimated reserves of 907 billion cubic meters.

At the Russia-Japan Trade and Industry Dialogue in Tokyo, Denis Khramov, deputy chairman of the management committee of Novatek, hinted at Japanese involvement in the Arctic LNG project as well. He said, “Unlike Yamal LNG, the partnership on Arctic LNG has not been configured yet, and we consider it as a significant and serious option for Russian-Japanese cooperation. Now that the project is being prepared the possibility to join the project for Japanese companies is rather convincing, and maybe even unique.”

Climate change makes Arctic energy resources more available, a significant development because, as the U.S. Geological Survey estimated, more than 20 percent of the world’s undiscovered hydrocarbon reserves are located in the Arctic.

On the surface, neither Japanese nor Russian officials are willing to characterize their relationship with China in the Arctic in contentious terms. Shiraishi also stated at the press conference, “We don’t see any competition in China’s presence in the Arctic region,” and Russian Deputy Prime Minster Dmitry Rogozin expressed Russian encouragement for China to increase the use of the Northern Sea Route for cargo shipping.

However, it is undeniable that China is a key factor pushing Japan and Russia closer together – despite the continued impasse over Ukraine. Japan naturally would want to balance China with any willing partner, but Russia also has an incentive to cooperate with Japan. It’s partly economic, as Russia wants to expand the number of clients it exports energy to so it does not have to be dependent solely on Chinese demand (as unlikely as that is to be satiated anytime soon). However, Russia’s motivations are partly military as well. Some observers hypothesized a connection between large-scale snap military inspections in Russia’s Far East and five Chinese naval vessels passing into the Sea of Okhotsk in July 2013. Last September, around the same time U.S. President Barack Obama visited Alaska, five Chinese naval vessels were spotted in the Bering Sea between Russia and Alaska for the first time.

Russo-Japanese cooperation in the Arctic is a region to keep an eye on, as there seems to be abundant possibility for international cooperation here – even as Russia’s diplomatic isolation continues.