Chinese military assets in the South China Sea have been widely publicized of late, with reports focusing in particular on the deployment of HQ-9 missile batteries and J-11 fighter jets to Woody Island in the Paracels. That, in turn, has sparked a fresh round of criticism of Chinese “militarization” of the South China Sea, particularly from U.S. officials.

“When President Xi was here in Washington, he stood in the Rose Garden with President Obama and said China will not militarize in the South China Sea,” Secretary of State John Kerry said on February 17. “But there is every evidence every day that there has been an increase of militarization of one kind or another.”

Admiral Harry B. Harris, Jr, the commander of U.S. Pacific Command, was even blunter in a Senate hearing on February 23: “In my opinion China is clearly militarizing the South China Sea. You’d have to believe in a flat earth to believe otherwise.”

Yet the recent military deployments to Woody Island are a problematic example to use if the goal is to provide evidence that China is militarizing the South China Sea. In the sense that militarization requires an alteration the status quo, there’s a huge difference between placing military assets on Woody Island – a naturally occurring feature that has hosted Chinese troops for six decades – and, say, on Fiery Cross Reef, which China has expanded by over 2 square kilometers over the past two years in order to construct an airstrip and harbor.

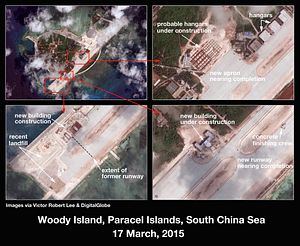

First, some basics: Woody Island , unlike recently expanded features like Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratlys, is a naturally-occurring feature — over 2 square kilometers in area, it’s the largest of the Paracels. Woody, known as Yongxing in Chinese, has been occupied by Chinese troops since 1956 – more than 30 years before Beijing belatedly sent troops to occupy any of the Spratlys. Currently, Woody Island is the seat of government for Sansha, a prefecture-level city established by China in 2012. According to China, Sansha technically administers both the Paracels and the Spratlys, as well as Macclesfield Bank and the Scarborough Shoal (“Sansha” means “three islands” in Chinese, referring to the Xisha/Paracels, Nansha/Spratlys, and Zhongsha groups).

Unlike most of the features in the South China Sea, Woody Island also touts a sizeable civilian population — “613 local residents,” mostly fishermen, when Sansha City was established in 2012, according to Xinhua. All told, including soldiers, Woody is believed to have over 1,000 residents. To accommodate that population – both military and civilian – the island is home to a government administration building, hospital, school, museums, bank, supermarket. Meanwhile, the island’s existing airport, in addition to its military role, hosts civilian flights to and from Hainan’s Meilan Airport. It can now accommodate Boeing 737s, thanks to the recent expansion of the airport.

Woody Island is also home to military facilities, and has been for decades. Even the two recent deployments – of HQ-9 missile batteries and J-11 fighter jets – aren’t unprecedented. As Admiral Scott Swift, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, told reporters, China has deployed HQ-9 batteries on Woody at least twice before (although both times were for military drills, which does not appear to be the case this time). Likewise, J-11s have been deployed on Woody Island before – including only a few months ago, in November 2015.

As Swift explained, that context matters: “This isn’t exactly something that’s new… So the real question is, ‘What’s the intent? How long is it going to be there? Is this a permanent forward deployment of this weapons system or not?’”

As experts at the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative noted in their analysis, the pre-existing facilities mean Woody Island housed anti-aircraft capabilities long before the deployment of HQ-9 missiles. “Woody Island has long been prepared for air defenses using its 8,900 foot (2,700 meter) airstrip, radars, and aircraft shelters,” AMTI pointed out.

That’s not to say that the recent moves on Woody Island are meaningless. They have implications for PLA capabilities in the South China Sea, including extending China’s anti-access capabilities – assuming that the deployments are permanent.

But the more important effect of the recent moves at Woody Island may be signaling of what’s ahead, presenting a possible model for future moves on China’s new facilities in the Spratlys. After all, as AMTI points out, “Woody Island has served as a model for Chinese development in the Spratly Islands, particularly at Fiery Cross, Mischief, and Subi reefs.”

The differences between militarization of the Paracels and the Spratlys should not be overlooked. As Bonnie Glaser, a senior adviser for Asia and the director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told The Diplomat, China militarized many of the Paracels “long ago. They are now deploying more advanced military equipment.”

It’s the Spratlys where China is currently “building lots of dual use capabilities, and trying convince others they will provide public goods and just defend their positions,” Glaser said.

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s famous statement that “China does not intend to pursue militarization” was also specifically made in reference to the Spratly Island. It’s the Spratlys, then, that will pose the real test of China’s intentions for the South China Sea.

There’s another key distinction between the Spratlys and Paracels: China doesn’t recognize any dispute to its claims in the Paracel group. Unlike the Spratlys, all of the Paracel Islands are both claimed by and occupied by China (thanks to China’s victory over the Republic of Vietnam in a brief battle for control of the features in 1974). Though Vietnam still claims the Paracels, China does not recognize that claim – and thus does not recognize the existence of a dispute (similar to Japan’s refusal to officially recognize a dispute over the Senkaku Islands). China argues that Vietnam renounced its claim in a communique from the North Vietnamese government in the 1950s.

Thus, when asked about China’s military deployments on Woody Island, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying told reporters, “The Xisha Islands are part of China’s inherent territory with no dispute at all.” She added that, because there is no dispute, the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, signed by China and ASEAN, “has nothing to do with” the Paracels. The DoC saw China and ASEAN agree, among other points, “to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability.”

That doesn’t necessarily mean that Beijing wouldn’t deploy military assets to the Spratlys, DoC or no. After all, China considers the Spratly Islands its sovereign territory as well. When asked last week if China would deploy missiles or similar equipment in the Spratlys at some point in the future, Chinese Defense Ministry spokesperson Wu Qian replied, “China has the legitimate rights to deploy weaponry on its own territory in the past or at present, temporarily or permanently, and to decide the kind of weaponry and equipment to be deployed.”

The potential for China to deploy similar capabilities on the Spratlys may be precisely why the current developments on Woody Island have raised so much concern. According to Glaser, “It increasingly looks like the Chinese want to hamper access and increase their control over air and sea space” in the South China Sea.

Yet, at the same time, the deployments on Woody Island, for the reasons discussed above, aren’t a great example of the sort of militarization U.S. officials and security analysts alike are watching for. And a focus on Woody Island’s missiles and jets might actually be counter-productive.

“I worry a bit about this knee jerk tendency toward hyperbole about Chinese militarization,” Gregory Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, told The Diplomat. “There is a real strategic challenge here for the U.S. and regional states—one that requires careful monitoring and calibrated policy responses, but is only undermined if the U.S. is seen as crying wolf.”

AMTI instead has emphasized the deployment of radar facilities to artificial islands in the Spratlys as a more concerning move in the long term. “This month’s deployment of HQ-9 surface-to-air missiles on Woody Island in the Paracels, while notable, does not alter the military balance in the South China Sea,” the report notes. “New radar facilities being developed in the Spratlys, on the other hand, could significantly change the operational landscape in the South China Sea.”