Luc Forsyth and Gareth Bright have set out on a journey to follow the Mekong river from sea to source. The Diplomat will be sharing some of the stories they’ve found along the way. For more about the project, check out the whole series here.

In the town of Nakasang, the main trading hub for those living near the Khone Falls, we explore the morning markets where we discover both the good and the bad of the local Mekong-driven economy.

One way to travel is by motorbike taxi. Photo by Gareth Bright.

It was around 4.30 a.m. and still pitch black when Batman came for us. We had given the motorcycle taxi driver his nickname after spotting the small superhero insignia that was welded to the front of his vehicle. Short and solidly built with a prominent belly that poked through the front of the loosely buttoned military jacket that he wore in lieu of a shirt, he hawked noisily in the gloom as he waited for us to pile into the rickety sidecar welded to the chassis of his Chinese motorbike.

A young boy runs along the bank of the Mekong river near the town of Nakasang. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

We had hired him on the spot the previous day because of his unusual voice, which never spoke normally but rather shouted in a deep throaty rasp. Every query was met with an intense barrage of hoarse yelling, and we immediately loved him for it.

We were heading to the early morning fish market on the banks of the town of Nakasang, and after a few failed attempts Batman was able to kickstart the bike into action. As it was the low-season for fishing, we’d had limited success in finding fishermen to talk with around the Khone Falls, and so had decided that the market was the one place where they would all congregate, regardless of the season.

People gather in the market in Nakasang. Photo by Gareth Bright.

The Judas Duck

Even though the sun was barely above the horizon, the market was already starting to hum with activity. Families gathered on the river banks to sell everything from charcoal briquettes to deep fried bananas, and fishmongers prepared their stalls for the arrival of the fishermen coming with their morning’s catch from the Mekong.

Fresh fish are brought to the Nakasang market every morning. Nakasang is directly upriver from the Khone Phapheng waterfalls, and the majority of commercial fish caught in the area ends up in the Nakasang market. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Because the Si Phan Don (4,000 islands) region was a popular destination for tourists and well established as a stop on the “banana pancake” backpacker trail, we were not an especially rare or exciting sight for the locals as we had been in the far north of Cambodia, and so for the most part they ignored us. In fact the majority of marketeers seemed so reluctant to talk to us that we initially thought they didn’t like tourists, but we quickly realized that their suspicions were caused by the dubious legality of some of their wares rather than because of any negative attitudes toward foreigners.

People gather in the market in Nakasang. Photo by Gareth Bright.

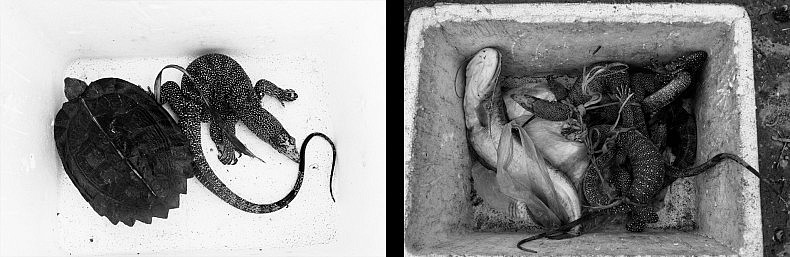

At many of the stalls, between the piles of fish bedded in crushed ice, were barely moving mounds of huge monitor lizards, bound at the legs and mouths. Some looked so near death that the only signs of life they exhibited were their blinking eyes, which fought against the encircling flies. In lesser numbers were turtles of varying sizes, stacked on top of each other inside styrofoam boxes. As the day progressed and more fishermen arrived to sell their catches, the piles grew steadily until the animals at the bottom were struggling to breathe under the weight.

A fish vendor shovels ice into a sack of fish to keep them fresh in the heat of the daily market in the town of Nakasang. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

This was a major legal grey area in Laos, our translator explained to us. On paper, trading these animals was explicitly illegal and carried harsh penalties, but in reality police turned a blind eye in exchange for small cash payoffs. This was hardly a surprising fact for either Gareth or me, as we well knew that animal welfare always came second to feeding one’s family in poverty stricken areas, but it was nevertheless difficult to witness animals being crushed to death by members of their own species as they all waited for an end that I’m certain they could all sense was coming.

Turtles, lizards and fish awaited their fate in the market. Photos by Gareth Bright.

Though it was not particularly objective from a journalistic standpoint, we even went so far as to enquire about buying the turtles so we could throw them back into the river downriver from the market, but they were surprisingly expensive at $30 each and somehow choosing one to free while leaving the rest to their fates seemed morbid. It’s not fair to fault people living so near to, or often below, the poverty line for doing whatever they can to earn the money they need to send their children to school or buy medicine for their elderly parents (particularly when we were carrying thousands of dollars worth of camera gear) but watching such overt suffering for hours on end was nevertheless difficult.

A single duck is permitted to scavenge among the stalls of the Nakasang market. Locals say the duck comes to the market everyday and it has become a mascot of sorts. Meanwhile, other ducks are less fortunate. Photos by Luc Forsyth.

Navigating through the throng of the market, without apparent concern for its own safety, was a lone white duck. For some inexplicable reason the market had reached an unspoken and unanimous decision that this particular duck would be allowed freedom of movement, and its more or less constant attempts to steal small fish would be tolerated. Considering that there were hundreds of live ducks hanging by their feet, too delirious to move from the blood rushing to their heads, one would think the duck would have gotten as far from this place of death as possible, but it seemed quite unconcerned with the danger of its surroundings.

Merchants in the market estimate that they are getting half the fish out of the Mekong that they got a decade ago. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Though it was possible that they all just had a soft spot for this particular duck, a more rational conclusion might have been that it served as a Judas, creating an artificial sense of calm among the other animals, which should have been collectively in a state of panic.

As midday approached and the market activity slowed and vendors prepared to pack up for the day, we managed to get a few words out of some of them before we too left. They estimated that they are getting half the fish out of the Mekong that they got a decade ago — a familiar story for us since starting this journey. One fisherman told us that his boat would have once been heaping with fish, where now there was only a small pile flopping around in the gunnels.

The morning fish market in Nakasang attracts large crowds, and is the commercial hub of the surrounding area. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Starting in the South China Sea, and continuing through Vietnam, Cambodia, and now into Laos, we had heard the same thing in different ways. Perhaps this was responsible for the increasing reliance on illegal wildlife trading, but it was impossible to know if this practice would have been stopped had the fish been more abundant.

Spiritual Connections

After waiting for the hottest part of the day to pass, we reconnected with Batman and drove into the countryside outside Nakasang to get a sense of rural life along this part of the river. As we passed through outlying villages we stopped to talk with several families, most of whom confirmed what we’d heard earlier that morning — there were not enough fish.

Batman drove us into the countryside outside Nakasang to get a sense of rural life along this part of the river. Photo by Garth Bright.

Each family had developed its own coping mechanisms; one man, 50-year-old Kham Bone, had turned to planting fruit trees which he could sell to Chinese biodiesel firms. His three children worked together to pot and plant the seedlings when not in school. Other villagers had taken a different approach and constructed giant bamboo fishing traps across the breadth of some of the Mekong’s tributaries. These were technically illegal, but as with the trading of turtles and lizards, seemed to be ignored by the authorities.

The most engaging and revealing conversation of the day came from Boun Yaang, a 67-year-old farmer and fisherman-turned-Buddhist monk who’d had 12 children and two wives before shaving his head and beginning his monastic life.

Boun Yaang, 67, is a Buddhist monk in a small pagoda in the village of Ban Thakao. Before he became a monk he was a fisherman and he still lives along the banks of the Mekong near the Khone Falls. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

“The Mekong is very important for this community,” Yaang told us. “It is for fishing, for farming rice, for gardening, for washing, and in the past it was for drinking as well.” He confirmed that the biggest and most impactful change was in the declining fish population, something that as a former fisherman he was certainly qualified to speak about.

“Before I could put a pot of water on the fire, walk down to the river and get a fish, and walk back before it was boiling. Now you need to have a boat and to go further away,” Yaang reminisced. “As a Buddhist, I am also connected to the river because we worship the Nagas (river spirits), and the rivers, and the trees,” he continued.

Monks in a village along the Mekong. Photo by Gareth Bright.

For all of this however, Yaang was no eco-warrior. He blamed Cambodians for the Mekong’s poor productivity though he had no facts to back up this position, and had little to no awareness of any of the proposed hydropower dams in his own nation. When asked what would happen in his community if there were no more fish in the river, he responded stoically: “We would build fish farms.”

As we left Nakasang the next morning, we had to wonder if Yaang’s attitude of ambivalence towards the Mekong would continue as we headed further north, toward the city of Pakse.

Buddhist monks collect alms from the residents of Nakasang in the early morning. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

This piece originally appeared at A River’s Tail.