From peaceful deities such as the 1,000-armed Avalokiteshvara and Goddess Tara to gods at the wrathful end of the scale – Yama, the god of death often seen enshrouded in flames; war goddess Begtse – to mathematical mandalas and more, Tibetan Buddhism has been visually expressing its core insights for centuries via an intricate style of sacred art known as thangka.

Literally “recorded message” in Tibetan, thangka paintings are the medium and the message for Buddhists across the Himalayas, from Tibet to Nepal. Drawing on Indian, Nepalese, Chinese and Kashmiri artistic influences, thangka grew into its own style in the seventh century. Normally taking the form of a scroll, thangka are painted or embroidered onto fabric made of linen, cotton, or silk for the loftiest subjects. The process of creating a thangka painting is multifaceted and labor intensive, employing the use of animal glue and naturally occurring pigments such as malachite, cinnabar and lapis lazuli.

Following a complex grid system, thangka artists must draw each figure and frill according to precise measurements and proportions stipulated by Buddhist iconography. In this sense, “the role of the artist is somewhat different than the inventor we know him to be in the West. The role of the artist becomes one of a medium or channel, who rises above his own mundane consciousness to bring a higher truth into this world.”

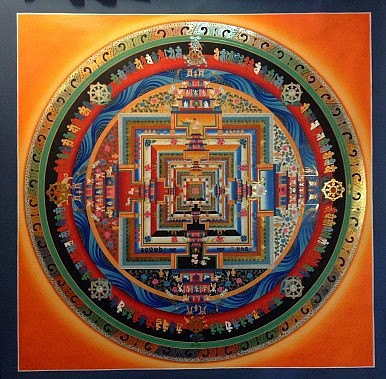

This results in paintings with an almost mathematical level of precision and symmetry, particularly in some of the more complex mandala patterns, which are meant to encapsulate the entire universe in a single frame. Finished works are lavishly mounted and range in size from a few square centimeters to several square meters. Depending on the scale and intricacy, a given painting can keep a team of artists busy for months or even years before it is complete.

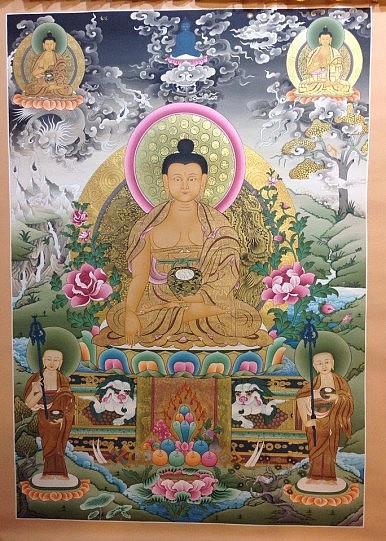

Depicting a swath of deities, visual narratives on the lives of saints and masters, and various manifestations of Buddha, thankas are objects of meditation and teaching tools as much as they are striking works of art. Traditionally, an itinerant teacher or lama would travel to a village, unfurl a thangka scroll and proceed to elucidate the message contained in the painting. In this way, thangka is an art form uniquely suited to the nomadic culture it evolved within.

Despite the depth of its roots, the thanka tradition is struggling today. The challenges facing artists are perhaps most visible in Nepal, where tourism took a major hit following the earthquake that rocked the country in April 2015. This damage was tragically multiplied by two local airline crashes this February. Yet, a community of thangka schools, staffed by master painters and attended by students from across Nepal, is working hard to keep thangka alive.

The Diplomat recently spoke with Ambar Lama, a figure in this movement who helped found the Old Tibetan Thangka Painting Academy, from his shop in Kathmandu about the state of thangka and the effort to preserve this vital part of Himalayan culture.

How did you learn to paint in the Thangka style?

I started studying when I was 7 years old under my father. I learned from my uncle also. I’m 30 now, but I’m still learning. I never had the chance to learn from my grandfather because I was too young when he passed away.

I come from a mixed family of lama lineage. My father is Tibetan and my mother is Nepali. Among my siblings, I have one younger brother who is 22 now. He has 14 years of experience and we could say that he is a master painter. For perspective, my uncle has 35 years of experience. He is a highly advanced master and an amazing teacher.

How is the skill passed down? Is it passed down within a family? Or can anyone go to a school and learn?

In fact, it’s very rare thing to see a thangka school in Nepal. Most people learn from family elders. But there is no rule saying that someone without family ties to the art can’t learn to paint in the thangka style. Anyone can choose to be an artist. They don’t have to come from a lama family.

Can you tell me about the school you’re running, the Old Tibetan Thangka Painting Academy?

I used to live in a very remote village. I grew up in a very rural part of Nepal, but came to Kathmandu 10 years ago. People are so poor in the villages. They have no skills, no education. After finishing school, many village children cannot go to university due to a lack of resources.

What we try to do at our school is help these children make it into university, alongside studying the art of painting thangka. We don’t charge students any fees to attend thangka courses. All of the money we are making comes from selling paintings.

I don’t personally have any formal education, so I couldn’t go to university. I feel that I’m doing my part to help others get formal education by helping to start this school. Right now we have 27 students, 10 master painters who serve as teachers. These teachers have a similar skill level to my father, although he is perhaps even more advanced than most of them.

What is unique about thangka?

Thanka is extremely difficult from a technical point of view. On top of this, there are many levels of meaning in one painting, which is meant to have a strong balance of artistic vision and feeling, but also deep spiritual meaning.

Many people today have lost their sense of connection to the spirit of life. Yet, if someone learns more about the real meaning of a mandala or becomes interested in some Buddhist deity, one painting can change their life. Of course, I’m not talking about money or something material. But coming into contact and understanding the real meaning of the art can change peoples’ feelings and ways of thinking.

Which subjects depicted in paintings are the most popular among buyers?

Tourists are the main collectors of thangka today. In particular, for visitors from the United States, Canada, Australia and Europe, mandalas are very popular.

Even if they are not Buddhist, I think that most people who are attracted to thangka are very open minded and still do connect with the art in a meaningful way. They tend to have a strong sense of appreciation for the skill involved and the beauty of the work.

How are Thangka paintings used within Buddhism?

The mandala, for example, is a representation of the universe, as well as samsara (the cycle of birth, life and death as conceived by Buddhism). All beings are in it together in a mandala. We are all living, suffering, being reborn. Through meditating on a mandala, and by visualization as well, we can achieve specific results. It’s a high spiritual practice.

Other thangka paintings, such as those showing the life of Buddha or the Goddess Tara, inspire believers. But these types of paintings are not used directly for meditation practice in the same way as mandalas.

People have different intentions and desires, which is why there are various deities in Tibetan Buddhism. For example, the Goddess Tara is a female manifestation of Buddha nature. But she is not higher or lower than any other deity. Each one just serves a different purpose. So it is with the various types of thangka too.

What is the state of the Thangka painting world today?

As a whole, artists are really struggling today. It’s due to a combination of things. For one, the massive earthquake that hit Nepal last year has really hurt tourism. Beyond this, there are political issues on the Indian border, making it more difficult to cross over. Not to mention infrastructure shortages and the recent plane crashes.

Due to these things, we are experiencing a weak tourist season right now in Nepal, which is making the economic situation very tough.

Is the culture surrounding thangka a politically sensitive subject in Nepal, or more crucially, in Tibet?

Of course, the political situation in Nepal is not quite as sensitive as it is in Tibet. But the culture surrounding Tibetan Buddhism is of course politically charged in both places.

Many people who moved to Nepal from Tibet do feel some pain from being unable to return to their homeland. So these people do sometimes voice their feelings about the Chinese government. For people such as these, political activism can still cause issues even in Nepal.

But even for those who are not involved in political activism, various ceremonies like celebrating the Dalai Lama’s birthday cause problems in Nepal too. There are restrictions on where you can gather with monks even in Nepal.

What are your thoughts on the future of thangka?

I think if things remain as they are now, artists will continue to struggle. The reality is that when an artist finishes one painting, if they cannot sell it in a local market, they may have to think about how they will eat for a time. Most artists are from poor backgrounds. So they either go back to working on a farm or manage to sell some paintings. I understand this situation very well, as I worked on my family’s farm as a child.

Many families work roughly six months of the year on a farm. That provides food for about half the year. For the other half, people have to either go work in a city or go work abroad.

But for those who do sell paintings, I’ll give an example. Say one painting takes 25 days to finish. It would likely sell for around $80-100. For a really big painting, the most expensive could sell for as much as $15,000. I have only one painting like that. As much as I’d like to have more, I can’t have them made because of the huge investment that it takes. (Laughs)

I think the key to thangka’s survival will be financial support. Nepali people cannot afford to hold exhibitions overseas. I’m still unable to do that kind of work. But in the future, I hope to make the kinds of connections that will allow me to do that. That would also allow me to explain the work that our school is doing and potentially get even more support.