Luc Forsyth and Gareth Bright have set out on a journey to follow the Mekong river from sea to source, The Diplomat will be sharing some of the stories they’ve found along the way. For more about the project, check out the whole series here.

Shortly after crossing into Laos, we arrived at the pounding waters of the Khone falls. Beyond being an awe-inspiring natural formation, the falls have both stymied the efforts to turn the Mekong into a trade highway and preserved the health of the local ecosystem.

An elevated section of the Khone Phapheng waterfalls (Khone Falls). The Khone Falls stretch the breadth of the Mekong river and prevent it from acting as a commercially viable transportation route. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

We could feel the water before we could see it. The deep bass rumbling of the expansive Khone falls was experienced not so much as a sound, but rather a pervasive sensation in the stomach that was both subtle and impossible to ignore at the same time.

We had crossed the border from Cambodia into Laos without incident. In fact, the customs checkpoint was so lightly used and understaffed that we probably could have walked into the country without showing our passports. Extravagant Khmer-style administrative buildings stood empty and unused, left to quietly rot in the humidity of the jungle. A pack of friendly stray dogs lazed in the no man’s land between the two nations, significantly outnumbering the immigration personnel.

The Khone Falls in Laos stretch the breadth of the Mekong river and prevent it from acting as a commercially viable transportation route.

Photo by Gareth Bright.

Less than 20 kilometers away was Nakasang, a small riverside town that served as the main jumping off point for travelers visiting the Si Phan Don (4,000 Islands) chain, as well as the main point of access to the Khone falls. We had come to explore the waterfalls and surrounding area partially because of their obvious visual appeal, but more importantly because of what they represented in terms of the Mekong’s past and future.

A man washes his feet along the banks of the Mekong river in the town of Nakasang. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

When the team of French explorers led by Ernest Doudard de Lagrée left Cambodia in 1866 with the mission of surveying the length of the Mekong, which was at that point a mostly blank and unknown space on the map for Europeans, their primary aim was to establish whether or not the river could be used as a trade artery to connect the French colonies in Indochina to the silks and riches of China. The journey was fueled purely by imperial economic ambitions, as evidenced (in comically stereotypical French style) by the fact that the small team carried just six boxes of scientific instruments with them compared to more than 700 liters of wine and several hundred liters of brandy.

Nakasang is directly upriver from the Khone Phapheng waterfalls, and the majority of commercial fish caught in the area ends up in the Nakasang market.Photo b y Gareth Bright.

Though the team would go on to be the first Europeans to navigate the entirety of the Mekong, their goal of establishing a trade route to China was thwarted early on by the Khone falls, a mighty chain of rapids that stretch along nearly 10km of the river. While even today, a century and a half later, the Khone falls hamper the Mekong’s utility as an international trade highway, the area is once again in the crosshairs of economic development.

Plastic bottles and other waste from the upstream tourist destination of Si Phan Don (4000 islands) collects below the Khone Phapheng waterfalls. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Untamed, For Now

Though the Khone falls dominated the landscape immediately south of the 4000 Islands, actually getting to them was somewhat problematic. An official tourist observation platform provided a lovely panoramic view, but was far removed from the fisherman we could see casting his net into the churning water below.

After slipping around a set of heavy wooden guardrails, we were able to scramble down a narrow dirt path and onto the wet rocks that defined the eastern periphery of the Khone Falls. In the wet season, with river levels at their peak, it would not have been possible to stand where we were. I had seen photographs of the area taken by colleagues shortly after the monsoon rains that showed the area as an uninterrupted mass of churning water, but at the tail end of an unusually dry summer, the rapids – while still impressively wild – were more subdued.

A man casts his fishing net into a pool of water above the Khone Phapheng waterfalls. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Though it would have been ideal to see the cascading water in its most dramatic state, the reduced flow allowed us to pick our way along the stony lip of the falls towards the fishermen. Had the falls been moving at full force, the only means of navigating across would have been a pair of rusted steel cables suspended limply between wooden posts that had been driven into the rocky banks at some unknown point in the past. Considering Gareth was nursing severely bruised ribs and I was wearing a pair of extremely cheap rubber sports sandals, walking on solid stone was the far safer option.

A fisherman walks through a rock field above the Khone Phapheng waterfalls. The rocks are exposed only in the dry season and will be under water when the monsoon rains fall and the Mekong rises to its full size. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

The single fisherman working this section of the falls dipped in and out of sight as he descended and reemerged from craggy valleys carved by millennia of fast flowing water. Well built and sure footed on the slippery rocks, he looked like consummate professional river fisherman. For nearly an hour we followed him as he cast, checked, and recast his hand net into the deep pools that pockmarked the area. He seemed completely unconcerned with our presence, and other than a polite smile, barely acknowledged we were there. Once the soft dawn light began to transition into the harsher glare of mid morning we asked our translator, Noy, to join us and facilitate conversation.

A man fishes in the pools above the Khone Phapheng waterfalls. Photo by Gareth Bright.

As Noy made his way towards I began to mentally formulate a list of questions I wanted to ask about the current state of fish stocks in the area, how concerned he was about the multitude of hydropower dams slated for construction along the Mekong in Laos, and what he thought about his children’s futures as Khone fishermen. But these ideas of a deep conversation on the ecological state of the river were brushed aside almost at once by the realities of the modern world.

A man casts his fishing net into a pool of water above the Khone Phapheng waterfalls. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

“He isn’t actually a fisherman,” Noy translated for us, “he only does this to get some extra food when he has a break from work.”

When asked what his real job was, Noy and the bemused young man went back and forth for a few minutes before Noy turned to us with an embarrassed grin.

“He is a photographer. He takes pictures of the tourists who visit the waterfalls.”

The Khone Falls in Laos stretch the breadth of the Mekong river and prevent it from acting as a commercially viable transportation route.

Photo by Gareth Bright.

Low Season, High Effort

After laughing off our own naivety, we left the tourist viewpoint and headed back towards Nakasang where we chartered a small boat to take us to the opposite bank of the Mekong, hoping to find a more authentic glimpse at life next to the Khone falls. Several locals warned us that it was low season for fishermen and it would be nearly impossible to reach the area where they worked at this time of the year laden with camera gear as we were, but we decided to try anyways.

A fisherman casts his net into the turbulent water below the Khone Phapheng waterfalls. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

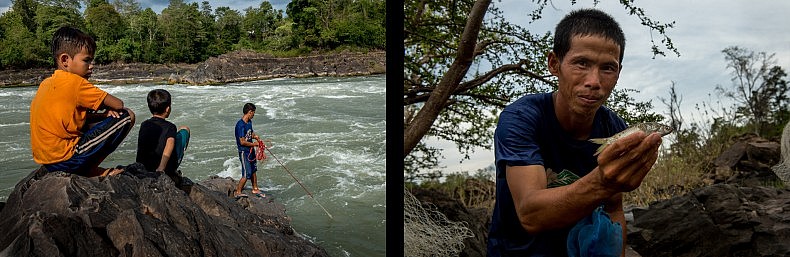

Predictably, the locals were right. It took several hours of fording chest-deep streams and bushwhacking along overgrown jungle paths before we found a single fisherman. Thin yet incredibly strong looking, Vong was in his 40’s and was followed by two young sons who watched him cast his net with keen interest.

Vong confirmed what we had been told earlier – this was low season, and his catches were small. For a few minutes we tried to press him on big-picture issues such as dam projects, but he seemed either unwilling or simply unable to comment, and so we let him be and joined his sons on a large boulder to watch their father expertly working in the churning water.

A fisherman and his sons in the Mekong in Laos. Photo by Gareth Bright.

After coming up empty on a few casts of his hand net from the river bank, Vong lowered himself into the swift currents and began hauling himself hand over hand along a lone wire that stretched from the Mekong’s western bank to a rocky island that stood in the middle of the river. It would have been impossible for Gareth or I to follow him while keeping our cameras dry, and truth be told I’m not sure if we possessed the brute strength, despite each being at least 20kg heavier and a foot taller than the wiry fisherman.

The young sons of a fisherman sit on the banks of the Mekong below the Khone Phapheng waterfalls, waiting for their father to return from his afternoon fishing. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

His sons quickly lost interest in us and so for most of the next hour our motley group sat in silence, watching Vong’s distant form cast and recast his net. When he returned with the last of the day’s light, he had a caught just three small fish, the biggest of which was smaller than the average sized computer mouse. Considering how much physical effort it had taken for him to get this tiny catch, it seemed impossible that they would provide a surplus of calories. But Vong seemed satisfied with the day’s work and led his sons away over the rocks before melting into the dense jungle beyond.

A Laotian fisherman on the Mekong works diligently in the low season. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Though we had learned virtually nothing about the state of the Mekong in Laos in terms of literal facts or eyewitness accounts, we had nevertheless gained a fleeting impression of a country far less developed than what we had seen in Vietnam and even Cambodia – though as we would find out over the coming weeks, the health of the Mekong and the greater natural environment was far from perfect in this landlocked nation.

A fisherman works on the Mekong in Laos, watched by his sons. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

This piece originally appeared at A River’s Tail.