Luc Forsyth and Gareth Bright have set out on a journey to follow the Mekong river from sea to source, The Diplomat will be sharing some of the stories they’ve found along the way. For more about the project, check out the whole series here.

For one of the first times since our journey began, we find ourselves in the unique position of not having a Mekong-related issue to report on. For several days we comb the area around Pakse, but ultimately we find a region of quiet calm.

A statue of Buddha sits overlooking the Mekong river in the city of Pakse. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

As soon as the heavy cargo truck pulled onto the shoulder of the highway we were immediately swarmed by vendors. They shoved bananas, plastic bags of sticky rice, and barbecued skewers of chicken gizzard through the wooden slats of the truck walls, sometimes receiving a few thousand kip (the name of the Laos currency) in exchange from the hungry commuters. Five minutes later the truck’s ancient engine roared back to life and we were off again, blasting the vendors with exhaust fumes and gravel dust as they turned to meet the next arriving vehicle.

Clouds hang low on the way to Pakse. Photo by Gareth Bright.

We were on our way to the riverside city of Pakse, the third largest in the country and the capital of the former Kingdom of Champasak. Straddling the confluence of the Mekong and Xe Don rivers, it seemed like a logical destination after leaving the untameable rapids of the Khone waterfalls, but as had so often been the case during the making of this journey, we had no real idea of what we would find when we got there.

With a population of nearly 100 000, it was a big city by Laotian standards and drew nearly half a million tourists each year; we figured there had to be something there. Yet every time we asked a local what we should see or do in Pakse, they would think for a moment and then shrug: “It’s pretty, but a little bit boring.”

Boring, we figured, was an opinion based on circumstance; what might be boring for a local could be fascinating for us.

Coffee beans on a tree on the Bolaven plateau outside Pakse. Photo by Luc Forsyth,

Caffeine Plateau

Eager to see what Pakse had to offer we arranged for a small truck to meet us at the unfortunate time of 4:30 a.m. to drive us the 100 km from the city to the Bolaven plateau. A 1300 metre tall edifice of rock that dominated the surrounding landscape, the plateau was once a place of immense suffering as one of the most heavily bombed theaters of the Vietnam War, but now it was better known for coffee than explosives. Being seriously dedicated coffee drinkers, both Gareth and I were looking forward to pursuing anything that gave us an excuse to drink more of it.

A River’s Tail moves away from the river to explore the coffee hills of Laos. Photo by Gareth Bright.

As our vehicle ascended the long, gently graded road that lead to the plateau, our ears popped periodically and we rose further and further into the misty cloud layer that hung over the summit. For the first time that either of us could remember since starting this journey we were not within walking distance of the Mekong or one of its tributaries, and the distance felt strangely unsettling after so many days by the water.

Originally cultivated by French farmers during the colonial period late in the 19th century and running into the middle of the 20th, coffee plantations began to appear on both sides of the road once we reached the plateau’s flat top. More or less at random we stopped at one, passing under tall gates made of an expensive looking hardwood before parking in the visitors area. Polished wood surfaces and metal appliances gleamed in the various reception facilities and it was clear that these plantations were not casual subsistence operations.

A young girl sits in a coffee tree on the Bolaven plateau. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

As we walked slowly through the plantation grounds, surrounded by coffee trees and squat tea bushes, it seemed odd to find very few people physically working save for a scattering of laborers cleaning debris from between the crop rows. A little confused by the lack of activity, we continued further into the compound until we eventually arrived at a rest area, much smaller and more rustic looking than the modern structures we had seen earlier. A distinguished looking man was the sole patron, sitting alone at a wooden table sipping green tea and smoking a long black cigarette.

Scene from a tea plantation in the Bolaven plateau. The plateau possesses a microclimate that makes it ideal for growing tea and coffee, which have become the biggest industries in the area. Photo by Gareth Bright.

“Bonjour,” he said as we approached and I scrambled to switch into French, which I hadn’t meaningfully used since leaving university. Pablo, a native French speaker, had returned to Phnom Penh before reaching the Cambodia-Laos border to sort through dozens of hours of video he’d recorded and Gareth, though fluent in multiple languages, spoke barely a word of French. My rusty language skills would have to suffice.

“Welcome to my plantation, please join me.” His French was smooth and his accent non-existent. “Would you like a coffee?” He waved to a waiter when we accepted, and he gestured for us to sit down.

Inpong Sananikone stands in front of a one hundred year old coffee tree on his organic plantation on the Bolaven plateau. A Laos-born French citizen, his plantation produces high quality tea and coffee for export around the world. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

His name was Inpong Sananikone, a Laos native who emigrated to France as a young man before returning to Laos in retirement to buy an existing plantation and reform it according to his own principles. “When I started this business I decided on three rules: It has to be welcoming, clean, and organic,” he said, using simple French vocabulary thankfully within my ability to understand.

As the drinks arrived, we asked about the absence of workers in the fields. “It’s not the season,” he said, “Come back in a few months and you can see the work.” Sliding the small cups of steaming coffee towards and after taking an appreciative sip of his own, he stared thoughtfully at his glass before musing “I had coffee with the French Prime Minister last year. It cost 15 euros and it was not as good as this.”

Life is just a bit slower in Pakse. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Uncertain of how to respond to such an unusual statement, we said nothing and instead sat quietly sipping our drinks. Obviously he had accomplished a great deal during his decades in France if he was meeting with the Prime Minister, but my language skills had already been stretched to the breaking point and I didn’t have the words to question him much further.

It wasn’t until the glasses were nearly empty that we noticed something was off. First my hands began to shake, first only a little, but shortly afterwards degenerating into an uncontrollable vibration. Sweat formed on my forehead and I could feel my heart pumping at close to twice its normal speed. Fearing that I could be on the verge of a heart attack, I looked over at Gareth for reassurance. His face was drained of color.

An independent organic tea and coffee grower stands in front of drying tea leaves on the Bolaven plateau outside Pakse. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

“Strong coffee is the secret to staying young,” Inpong said, possibly noticing our jitters. “I put 7 grams of coffee into every cup of water.” Even as habitually heavy coffee drinkers, we were both shocked by the power of the drink. As we stared at him in disbelief, he asked rhetorically “Well, did you want to drink water, or did you want to drink coffee?”

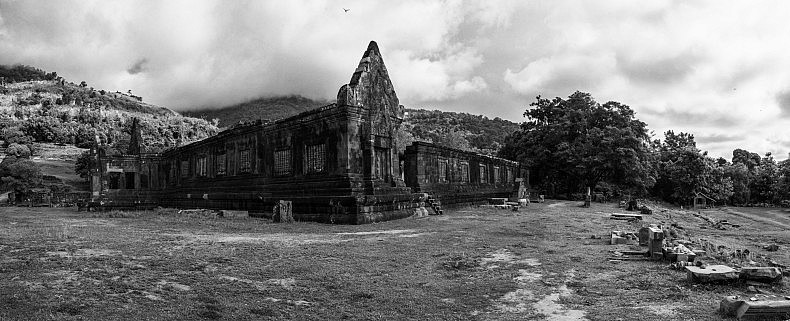

The ancient temples of Wat Phu. Photo by Gareth Bright.

The Ghosts of Empire

After the extremely unpleasant caffeine high of the Bolaven plateau, we resolved to stay closer to the water for our remaining time in Pakse. After several days we saw what the locals had been talking about when they said that the city was “pretty, but a little bit boring;” although for us boring was the wrong choice of word. There was nothing boring about the area; it was both beautiful and welcoming, but things around Pakse just moved at a slower pace.

Rather than fight against the area’s nature, trying to force interesting river-related stories to present themselves to us, we surrendered to the casual rhythm of life in southern Laos and spent several days taking in the area.

Hundreds of privately donated statues sit in front of the Phon Salao pagoda in Pakse. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

We visited the ancient temples of Wat Phu, constructed by the same Khmer Empire that built the world-famous Angkor Wat complex in the jungles outside Siem Reap, Cambodia. The aesthetic similarities were striking, and compared to the constant crowds and inflated prices of the far more heavily touristed temples in Cambodia, we had Wat Phu entirely to ourselves for several hours.

Stone carvings at Wat Phu. Photo by Gareth Bright.

Later we chartered a boat to the silk producing island of Don Kho, getting back on the the Mekong for the first time in several days. Again, rather than aggressively hunt for river-related social stories to tell we simply walked across the island, talking to people we met from small families digging for edible grubs to young men and women working silk looms under the shade of stilted houses.

Monks make their morning round to collect alms from the villagers on the island of Don Kho. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

In many ways our time in Pakse was like a holiday within the larger journey. Initially we felt frustrated by the lack of activity, having placed a huge amount of pressure on ourselves thought the trip to find and visually document the Mekong’s stories. Yet once we accepted Pakse for what it was, we were able to step back and enjoy the beauty and history of Laos’ sparsely populated south.

Woman spinning on the island of Don Kho. Photo by Gareth Bright.

But all vacations must come to an end, and both Gareth and I were eager to get back to work. Most people we’d talked to in Pakse said that the rest of southern Laos would be much the same as what we’d seen in the last days, so we boarded a torturous 18-hour overnight bus and headed north to start investigating what is arguably the most controversial form development on the Mekong – Laos’ hydropower dams.

People pray to a large statue of Buddha overlooking the Mekong river in the city of Pakse. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

This piece originally appeared at A River’s Tail.