In 1909, a chemist-turned-photography pioneer received the blessing of Russian Tsar Nicholas II to document the empire in color. Using a train car equipped with a darkroom (provided by the tsar) and two permits that granted him access to restricted areas, Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, born in 1863, would go on to document Imperial Russia on the eve of great change. Within the decade, the tsar would be dead and Imperial Russia on its way to becoming the Soviet Union.

Left: Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (right, front) and two men in Cossak dress seated on the ground.

Right: Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (far right), an official and four railway workers riding on a railroad handcar.

The details of Prokudin-Gorsky’s life are littered with rumor and buried in the ash of empires. It’s said Prokudin-Gorsky studied with Dmitri Mendeleev during the two years (1886-1888) he attended university in St. Petersburg. In the introduction to a 1980 book, Photographs for the Tsar, historian Robert Allshouse writes that “perhaps he was inspired by the example of his teacher, the brilliant chemist D. I. Mendeleev… In 1922, in his autobiographical notes, he remembered his studies with Mendeleev with pride, recalling how in 1887, at the age of 53, the professor had taken a solo balloon flight to observe the solar eclipse–demonstrating in one action the exploratory nature of science while pointing out the yet uncharted vistas of the scientific frontier.” But Prokudin-Gorsky left university before graduating.

The son of an old noble family, Prokudin-Gorsky married the daughter of a scientist active in the Imperial Russian Technical Society (IRTS). Prokudin-Gorsky joined the IRTS in 1889 as his focus shifted from chemistry more firmly toward the technology and art of photography.

Left: Church of the Resurrection on the Blood, Saint Petersburg.

Right: Winter sunset from Papula hill, Vyborg.

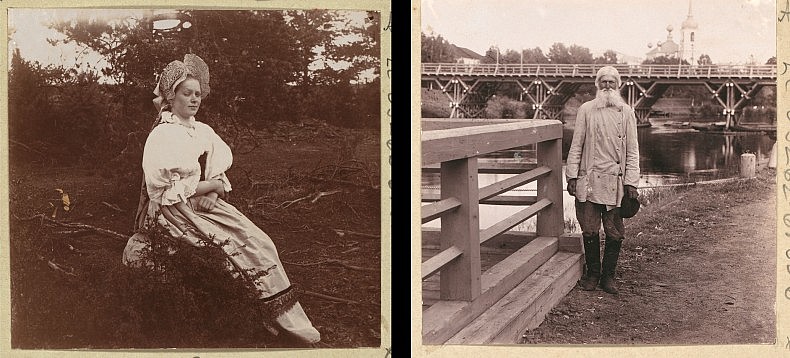

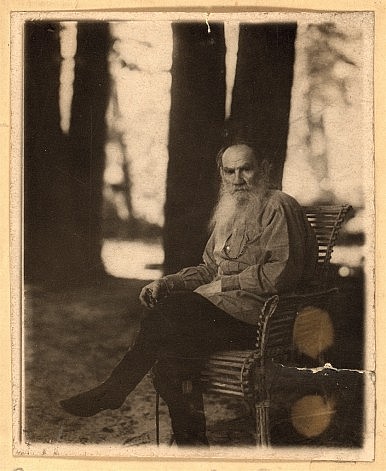

Leo Tolstoy in May 1908.

Prokudin-Gorsky studied with the pioneers of color photography, exhibited his works, and delivered papers from St. Petersburg and Moscow to Berlin and Paris. In 1855, a Scottish physicist named James Maxwell proposed using the “three-color method” to produce permanent color images. In 1861 he proved it was possible to generate color images using red, green, and blue filters–layering the three produce a full-color image.

It would be at least three more decades before other photography pioneers like Germany’s Adolf Miethe–with whom Prokudin-Gorsky studied in Berlin in 1902–would develop commercial cameras to make the taking of color photographs more or less practical.

In time Prokudin-Gorsky caught the eye of high society in Imperial Russia. In 1908 he photographed Leo Tolstoy. The next year Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, the tsar’s youngest brother, made an introduction that resulted in an imperial blessing for Prokudin-Gorsky’s grand idea to photographically survey the Russian Empire.

Between 1909 and 1915, Prokudin-Gorsky made several trips around the empire, documenting infrastructure, architecture and people. In 1910, the Tsar hosted a formal viewing of Prokudin-Gorsky’s survey of the the Mariinsky Canal system (now known as the Volga-Baltic waterway) and the Ural mountains.

Left: Pinkhus Karlinskii. 84-years old, with 66 years of service. Supervisor of Chernigov floodgate.

Right: Epiphany church in the village of Ust-Boiarskoe, Olonets Province.

In March 1910, the Tsar’s court held a formal viewing of Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs of the Mariinsky Canal system and industrial areas in the Ural mountains. Nicholas II wrote in his diary that Prokudin-Gorsky had shown him “beautiful shots of color photography from a trip through Russia to the Urals.”

The next month, Prokudin-Gorsky petitioned for permission to photograph widely in Tver Oblast, the source of the mighty Volga river. Prokudin-Gorsky was particularly interested in churches and monasteries. That summer he received an imperial edict granting him the approval he sought.

Left: Boris-Gleb Monastery, Torzhok.

Right: Cathedral of the Transfigured Savior and the Church of the Entry into Jerusalem in Torzhok.

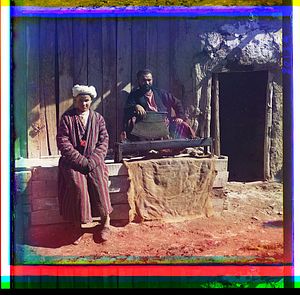

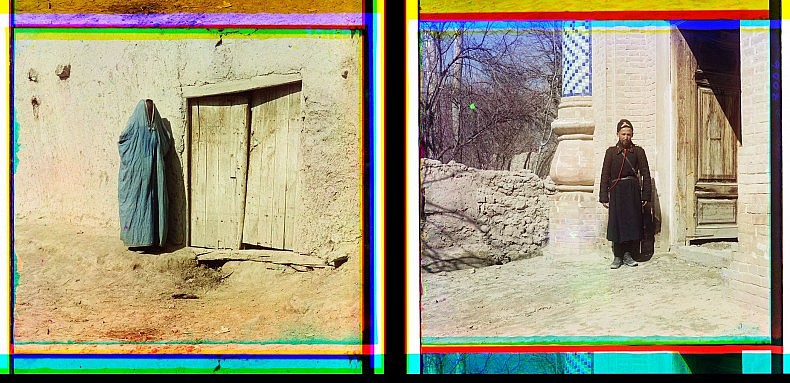

In 1911, Prokudin-Gorsky traveled through Turkestan, visiting the iconic heartland of Central Asia: the cities of Bukhara and Samarqand. He’d visited the region before, but photographs from his 1911 trip are some of the only surviving images of that place and time.

Left: Sart woman, Samarkand.

Right: Policeman in Samarkand.

He photographed the last Emir of Bukhara, Mohammed Alim Khan, stern and stately in a blue coat as well as his minister of the interior, festooned with a red sash and Russian medals. Bukhara had become a Russian protectorate in 1873, but the emir ruled over internal affairs. Alim Khan became emir in 1910 after his father’s death. He managed to initially hang onto power as the Russian Revolution raged through the region only a handful of years after Prokudin-Gorsky immortalized him in color.

The Bolsheviks established a hold in Tashkent and tried, unsuccessfully, to take Bukhara in the spring of 1918. Although Alim Khan tightened control and expelled those sympathetic to the Bolsheviks, in 1920 the Red Army returned with Mikhail Frunze at its head. The emir fled first to Dushanbe and then on to Kabul, Afghanistan, where he died in 1944.

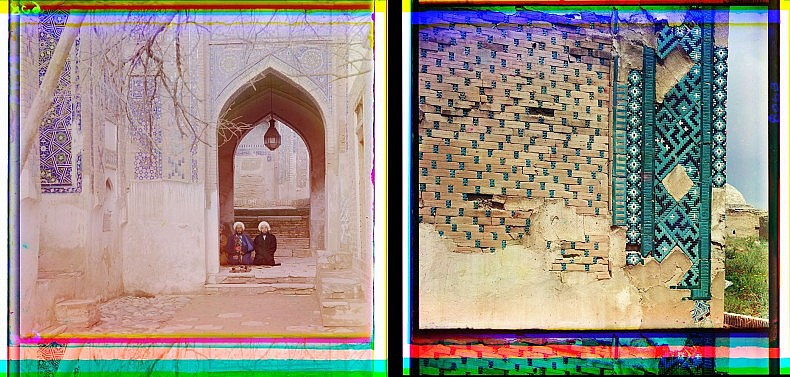

Left: At entrance to the Passage of the Dead. Samarkand.

Right: Outside view of the Passage of the Dead, from the left. Samarkand.

Prokudin-Gorsky would also die in 1944, far from the country he’d chronicled.

After his travels in Central Asia, Prokudin-Gorsky worked on several other expeditions, including one commemorating the Napoleonic campaigns 100 years before. But as the clouds of war–what would become World War I–darkened on the empire’s horizon, Prokudin-Gorsky’s official sanction and funding ended, save for a brief project in 1915 to photograph the Murmansk railroad.

In August 1918, Prokudin-Gorsky left Russia for Norway on an official trip but he did not return. The tsar and his family had been killed the month before as the Russian Revolutions unfolded. In his notes, Prokudin-Gorsky wrote:

With the arrival of the Revolution in Russia, the collection was fully in danger of being lost, and it remained under this threat for several years. However, thanks to a successful sequence of events, I was able to receive permission to export its most interesting portion. Excluded generally were photographs which had a strategic significance, which were of little interest to the broad public, and pictures taken throughout Russia in various locations, but not bound together by a common idea or system.

Prokudin-Gorsky found his way to Paris by 1920 and spent most of the rest of his life in France. A month after the August 1944 liberation of Paris, he died.

In 1948, four years after Prokudin-Gorsky’s death, his heirs sold what remained of his collection to the Library of Congress for $3,500–though family legend, recounted in this account of how the Library of Congress acquired the collection, says $5,000. The collection contained 14 catalogue-albums and 1,902 triple-glass negatives.

Victor Minachin of the Russian Academy of Sciences wrote, “Suffice it to say that not one glass negative from Prokudin-Gorsky’s Russian period has yet to be found outside the Library of Congress, even though it is known from sources that the total number of such negatives exceeded three thousand.”

In 2001, the Library of Congress held an exhibition of Prokudin-Gorsky’s images titled The Empire That Was Russia: The Prokudin-Gorskii Photographic Record Recreated and a few years later partnered with a computer scientist to create color composites from digital images of the negatives. The collection is available to peruse, though you may want to clear an afternoon to get lost in the empire that was.