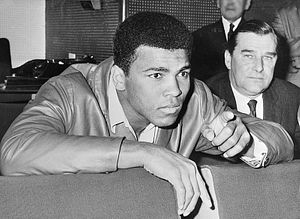

At Muhammad Ali’s funeral last week, one of the most moving tributes was delivered by the comedian and actor Billy Crystal. There were moments of levity, of course. “He was beautiful. He was the most perfect athlete you ever saw,” Crystal regaled the gathered mourners, “and those were his own words.” But there were serious ones, too.

At the peak of his career, Ali declined to trade in his gloves for a gun and join the the U.S. war in Vietnam. Assuming a combat role, Ali declared, would be an affront to his religious and political convictions. “There were millions of young men my age, eligible for the draft for a war we didn’t believe in,” Crystal recalled. “It was Ali who stood up for us by standing up for himself.”

By refusing induction in the army, he found himself pitted against his most formidable opponent yet – the U.S. government. Ali paid a heavy price for his defiance. He was stripped of his heavyweight title, deprived of his passport, and widely vilified. Until the Supreme Court eventually ruled in his favor, he was banished from the ring and faced the prospect of abiding his best years behind narrowly spaced bars.

In 1966, the same year that Ali became eligible for the draft, my organization, Amnesty International, explicitly adopted a policy on ‘conscientious objectors’ – people who are eligible for conscription but refuse to perform military service for reasons of conscience or profound conviction.

It took the position that conscientious objectors imprisoned because of refusing military service were ‘prisoners of conscience’. Five years earlier, Amnesty was founded to fight for the freedom of such prisoners– people who have been imprisoned not for crimes committed, but because of their peacefully held political, religious, or other beliefs based on their conscience.

“It has been said that I have two alternatives,” as Ali told reporters at the height of the controversy, “either go to jail or go to the army. But I would like to say there is another alternative. And that alternative is justice.”

Around the world, there are hundreds who are still denied that third alternative. Since we began fighting for the rights of conscientious objectors, Amnesty International has documented cases including in Argentina, Cyprus, Eritrea, Israel and the Occupied Territories, Turkey, Belarus, Greece, Norway, and, most notably, South Korea – home to most of the world’s currently imprisoned conscientious objectors.

Song In-ho is one of the more than 540 South Korean men currently imprisoned for refusing compulsory military service. As with an overwhelming majority of the cases, he is a Jehovah’s Witness. (The remainder refuse on grounds of other religious beliefs, or because they have moral, ethical and humanitarian reasons for doing so.) According to the tenets of their faith, Jehovah’s Witnesses oppose any form of militarism, including military service.

Since the Korean War, according to the Korean branch of Jehovah’s Witnesses, more than 18,000 adherents have been forced to make the invidious choice between following their deeply held beliefs and obeying the law. The penalty of imprisonment violates their human right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Song is 26 years old and is a recent college graduate. Once conscientious objectors are convicted, their fate is sealed. Appeals are so often unsuccessful that many no longer attempt to challenge their convictions.

Once out of prison, conscientious objectors struggle to secure employment, and are consigned to the margins of society. “I was born a criminal,” Song told Amnesty International’s researchers before he was sent to prison. “All my life I felt like I was imprisoned because I knew that I would be sent to jail.”

Song’s father tried to dissuade him from becoming a conscientious objector. As a member of an older generation, he grew up at a time when Jehovah’s Witnesses were often publicly humiliated, and even beaten and tortured. Now, they are no longer subject to such treatment, but they are still cast as a mutinous minority, tainted by allegations of treason.

Since his death, South Koreans have recalled how Muhammad Ali paid a visit to Seoul forty years ago, after vanquishing Joe Frazier in the “Thrilla in Manila” and recapturing his heavyweight title. There, he encountered a hero’s welcome, touring the streets of the capital, perched on the backseat of a top-down convertible, waving to crowds. “When I go back to America and throughout my tours I will tell people how nice Korea is,” he said.

The best way South Korean authorities can honor the memory of their famous guest is by honoring his hope that “the alternative of justice” should triumph over the alternative of jail for conscientious objectors. This would mean releasing Song and others currently behind bars, scrubbing their criminal records clean, recognizing the legitimacy of their beliefs, and enabling them to play their part as full members of society.

Ashfaq Khalfan is director of the Law and Policy Program at Amnesty International.