Of the approximately two million Chinese Koreans living in China, about half reside in Jilin Province, one of the country’s three northeastern provinces. Jilin comprises most of China’s border with North Korea and includes the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture — one of 30 administrative districts within the People’s Republic of China that are ruled, to some degree, independently of the central state. Given such a strong Korean influence on the region, it may seem logical that of Jilin’s ethnic Korean population many (if not most) would identify with one or both of the Koreas. Ethnic Koreans are, after all, described in Korean as tongpo; brethren abroad, compatriots borne of one ethnicity but living beyond the borders of their native land.

However, while this characterization generally holds true for older Chinese Koreans, in particular those who fled across the border to North Korea during the famine years of the Great Leap Forward and the mayhem of the Cultural Revolution, it is by no means applicable to the youngest generation. For them, the contemporary connection with South Korea is little more than functional, while that with North Korea barely exists at all.

Having grown up in the era of China’s rise, at a time when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has shown very little practical interest in the preservation of ethnic minority cultures and devoted a great deal of attention to forging some kind of “unified” Chinese identity, today’s youth of Yanbian identify as resolutely Chinese. In this brave new world, the pull of the “Korean Wave” and South Korean-based education and employment opportunities lack the power to shake China’s national foundations.

In its early years, the CCP took up a carbon copy of the Soviet Union model for governing the multitude of ethnic minorities that fell under its control, and in 1952, when ethnic autonomous rule formally arrived in this corner of Jilin Province, relative administrative autonomy and an acceptance of dual national-ethnic identities followed. One could identify as an ethnic “other” (i.e., not Han) whilst remaining nationally Chinese; indeed, an inclusive embrace of diversity was desired.

For China’s 55* officially recognized ethnic minorities (in addition to the Han majority) there was nothing unduly appealing about being Chinese in those days. States that fail — as the People’s Republic repeatedly did — to deliver basic public goods or a stable political and economic environment do not tend to readily generate loyalty and enduring feelings of patriotism and national pride. As a consequence, many Chinese Koreans who came of age in the turbulent years of the 1960s and ’70s are said to hold ambivalent or even anti-CCP attitudes.

But the young tell a different story.

Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening” marked the beginning of the end of China’s era of economic uncertainty. Events at Tiananmen Square in June 1989 were a tremendous shock to the system, but things calmed soon enough as Deng — the kingmaker — moved Jiang Zemin from Shanghai to the top job in Beijing and the nation’s economic course was reaffirmed: upwards.

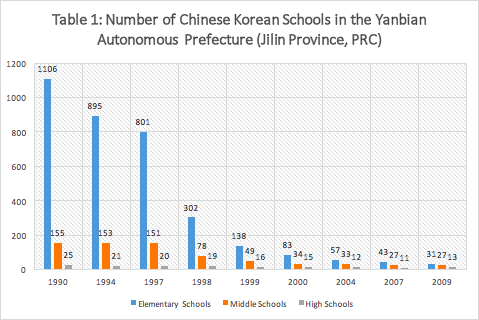

The government was in no mood to let a surfeit of independent spirit get in the way of the country’s trajectory, and this — coupled with the disintegration of the Soviet Union — necessitated a recalibration of national policy toward ethnic minority education. The impact was readily felt. In 1990 there were 1,106 Korean elementary schools in the Yanbian autonomous region, but this was down to just 138 by 1999 and 31 another decade after that. In the same period, 155 middle schools withered to 49 in 1999 and 27 in 2009, and 25 high schools shrank back to 19 in 1999 and then lost a further six in the following ten years (see Table 1 below).

The same pattern has been repeated — and amplified — elsewhere in Jilin. In 1991, 26 Korean middle schools were in Liuhe County, an administrative district of the industrial city of Tonghua in the west of the province, but by 2011 there remained only one. Another of Tonghua’s administrative areas, Ji’an, which borders the North Korean town of Manpo, had 14 schools in 1991, but in 2011 this number was also one. The pattern is repeated across the region.

Where did all the children go? Some certainly now live in South Korea, where immigration authority statistics show that the Chinese Korean diaspora, a mere 7,400 strong in 1995, now numbers more than seven hundred thousand. However, a great many more are enrolled in Chinese schools, where they study in Chinese and receive a Chinese education. Ultimate destination of the students aside, one thing is abundantly clear: the education of developing young Chinese Korean minds in the Korean language is a rapidly declining phenomenon.

Source: Yanbian Autonomous Prefecture Office of Education, cited in “Yanbian’s Chinese Korean Population Decline and Ethnic Education Crisis”

The reasons for the dominance of Chinese-language education among Chinese Korean youth, a local university professor informed us during our recent visit to the region, are twofold: First, sustained economic growth and development has altered perceptions of the Chinese state and what it means to be Chinese today. While political challenges to the CCP’s right to rule exist, economic opportunity for those who more fully assimilate, reinforced by a sense of pride in being Chinese, means more people (parents prominent among them) are willing to buy in. And second, in part a response to the challenges facing the Party today, the CCP has changed its nation-building strategy. Whereas in the past it was possible to be Chinese and ethnically Korean, today one is expected to be thoroughly Chinese.

Taken together, this provides a powerful explanation for not only the decline of Korean-language education and Korean ethnic consciousness, but also the success of Chinese nation-building — at least in Yanbian and the Chinese Korean populated cities of Northeast China.

Conversations with Chinese Korean youth suggest as much. Indeed, when asked to reflect on their Korean identity, a common response is borderline incredulity: “Why? We are Chinese.” Of course, young people are not unaware of their ethnic difference vis-à-vis the majority Han; simply, it is not a defining characteristic of their national identity. Reflecting thoughtfully on their own educational experiences, we were told that students receive a minjok (ethnic) history education that situates the (Korean) ethnic community as a factor in the broader struggle of the Chinese state. Education about other ethnicities is one thing, but education about other states, namely the ROK and DPRK, is treated in the same way as a British youngster might learn the history of France or Germany, or a Canadian might approach the study of his or her giant southern neighbor. They are taught as places abroad — foreign lands.

And while South Korea has all but entirely surpassed North Korea in the minds of younger Chinese Koreans, the connection with South Korea is itself a tenuous one driven by little more than a weak cultural affinity and a functional relationship. South Korean cultural production is sexy and attracts adherents all throughout Asia, but a Korean Wave does not make a Korean national identity. The ROK is also a rich country that speaks a language that some — though by no means all — Chinese Koreans are competent in, and this opens up the road to jobs and education that they can utilize. But primarily this furthers life goals back home in China. Degrees and work experience in South Korea are highly valued, but as functional aspirations – means to an end. The goal is not to return to the native homeland, but rather to settle comfortably in Beijing or Shanghai, the center(s) of the aspiring Chinese world order.

Steven Denney is a doctoral student in the department of political science at the University of Toronto. He is the managing editor of the research site Sino-NK.

Christopher Green is a PhD candidate at Leiden University in the Netherlands. He is currently co-editor of Sino-NK and formerly worked as Manager of International Affairs for Daily NK in Seoul.

*A previous version of this article said there were 56 ethnic minority groups in China.