Luc Forsyth and Gareth Bright have set out on a journey to follow the Mekong river from sea to source. The Diplomat will be sharing some of the stories they’ve found along the way. For more about the project, check out the whole series here.

Outside the northern city of Luang Prabang, we explore the relationships between humans and domesticated elephants. Over four days we learn about the bond formed between the animals and their handlers and the realities of the ecotourism and logging industries’ use of elephants.

Mahout, or elephant riders, direct their elephants through the river. Photo by Gareth Bright.

“When I came here, I didn’t know anything about elephants. I was a little afraid of them,” Son Phet admitted. A 24-year-old mahout, or elephant rider, Son Phet did not look afraid of the giant animal anymore as he stood fully upright on its head. Khoun, the 47-year-old female he was partnered with, hardly seemed to notice his weight.

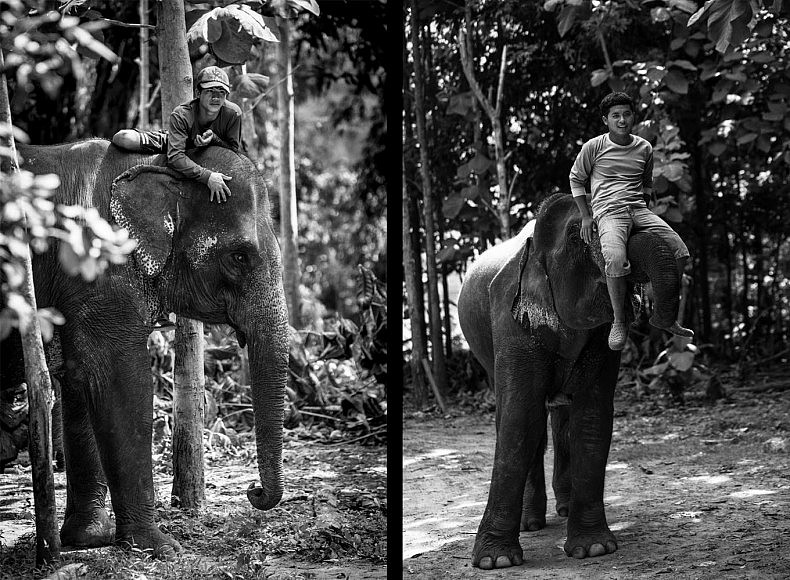

Son Phet, 24, has been working as a mahout for nearly two years. His current elephant, Khoun, is 47 years old. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

After the last week of investigating the impacts of Laos’ hydropower dams on the local populations, we had come to an elephant camp outside Luang Prabang to try and learn more about the relationships between people and animals along the Mekong. We had seen shockingly little wildlife during the the last months of travel. Apart from a brief visit to a national park and bird conservancy in Vietnam, most of the animal populations and habitats we’d encountered had been in bad shape. We needed to be reminded that the Mekong was a river that was not solely the domain of humanity.

Laos has an estimated population of just 400-600 wild elephants remaining. Photo by Garth Bright.

Admittedly, visiting a man-made camp where elephants were closely tied to their human partners was not the purest means of learning about the lives of the animals. But as Laos has an estimated population of just 400-600 wild elephants remaining, with our limited resources we stood little chance of interacting with them in their natural environment. Even with this compromise in mind, we felt it was important to try and gain some understanding of the enormous mammals’ situation in 21st century Laos.

After all, the country’s historic nickname was Lane Xang — the Land of a Million Elephants.

Mahouts wash their elephants in the Mekong river. The elephants visit the river at least twice a day to keep them cool and hydrated. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Courting an Elephant

“I heard that one of the older mahouts had a motorbike accident,” Son Phet explained when we asked what prompted him to become a professional elephant handler. “I knew about this place because my village is quite nearby and I had played with elephants a little before, and so I decided to apply.”

Mahouts say their bond with their elephants is based on trust; little else could get the 3 tonne mammal to move save trust or violence. Photo by Gareth Bright.

For mahouts like Son Phet, whose job security depended on being able to control his elephant while keeping it in good health, abusing the extremely valuable animal (buying an adult female can cost far more than a luxury SUV) would be a sure way to get fired. On top of this, beating an elephant into submission could create short term acquiescence, but in the long run made sure the mahout would live in perpetual danger.

Left: Son Phet, 24, with his elephant Khoun, 47.

Right: Boun Phan, 22, with his elephant Kham, also 22. Photos by Luc Forsyth.

“Elephants hide their emotions,” Son Phet told us when we asked him about the risks involved with his job. “It can be very difficult to tell if they are happy, sad, or angry. If you treat them badly they will hide their feelings, but they will never forget. They will wait and let you think everything is ok, but they might wait until you are alone with them in the jungle and then kill you. They don’t forget.”

The thought of such a powerful creature biding its time behind a mask of calm until it could exact the ultimate revenge on an abusive human was both fascinating and terrifying in equal measure. Of course, Son Phet was taught this when he accepted the job, and so knew that the only way to gain real control required time and patience.

“Elephants hide their emotions,” Son Phet said. Photo by Gareth Bright.

The basic formula was simple: stay in nearly constant contact with them for roughly a month until sufficient trust was earned. That contact involved everything from feeding the elephants, playing with them, and bathing them in the Mekong to keep them cool and clean. Except for when the elephants were taken into the jungle where they slept for the night, the mahouts were seldom out of sight of their animals, even long after a trusting relationship was established. Yet like any relationship, complete control was always out of reach. “You can never really have 100 percent control,” Son Phet explained. “The best you can do is maybe 95 percent. They can always choose not to listen.”

When we asked Son Phet to describe how he felt about Khoun after spending more than a year together, his response was unashamedly tender: “She is everything. My friend, my family, my wife.”

A mahout fits his elephant with a bench to carry tourists. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Beasts of Burden

As much as we were moved by the close relationships between man and elephant we had witnessed over the last few days, we knew that Khoun and the other animals at the Luang Prabang camp were not free in the true sense of the word. They were treated with absolute compassion and kindness, but still they remained indentured to their owners and spent nearly every day carrying tourists on their backs. Yet from our research and pre-trip conversations with elephant experts, we knew that employment in the ecotourism industry was far preferable to the other jobs elephants were often forced into.

Not all elephants are employed in ecotourism–such as taking these children for a ride. Photo by Gareth Bright.

According to the Elephant Conservation Center, there are currently more elephants employed by the logging industry in Laos than there are in the wild. Laos is rich in valuable hardwoods such as teak, and its mountainous terrain and the low budgets of many logging operations mean hiring industrial machinery is not always the most effective option for harvesting lumber. Elephants, with their enormous strength and ability to navigate both on land and in water, are often recruited into the labor force.

Chinese tourists gather around elephants to take photos outside Luang Prabang. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

The owner of the camp where we’d been staying agreed to show us where we could see the use of elephants in the logging industry for ourselves, and so early on our final morning in Luang Prabang we were dropped off at a small crossing on a minor tributary of the Mekong. As we sat in a leaky fishing boat that served as the only means of crossing we could hear the distant sound of something crashing through the water well before we saw it.

An elephant hauls teak logs from the Nam Ou river to shore so they can be transported to lumber mills. Photo by Gareth Bright.

When the elephant, a 35-year-old female named Seub, round the bend in the river, it was a truly awesome sight. Outfitted with a thick harness, it dragged a massive section of a freshly felled tree at the end of lengths of heavy-looking chains. It was the first time we had actually experienced the full extent of the animal’s power; with each determined heave forward it was apparent just how strong it was as it heaved the log over a sandbar and into the flowing river beyond.

An elephant drags a log out of the Nam Ou river as her mahout watches on. Photo by Luc Forsyth.

Its mahout sat cross-legged on Seub’s head just above the river’s current as the elephant swam steadily across to the opposite bank, the weight clearly much easier for her to manage with the aid of the water’s buoyancy. Once ashore, the mahout barked commands to Seub, provoking the final burst of power needed to beach the log. Seub was then unhooked from her chains and let to a thicket of dense grass to graze for a while before heading back across the river to haul another section of teak.

A mahout climbs back up his elephant, ready to pull more lumber up the bank. Photo by Gareth Bright.

In all, Seub would be able to make roughly 10 of these trips in a day, earning around $150 for the loggers for every cubic meter of lumber she delivered. If she wasn’t sick or tired and worked at maximum speed, her mahout told us, Seub could pull more than $10 000 worth of wood across the river in an 8 hour work day. It was difficult and dangerous work for both the elephant and her mahout, and since many small scale logging operations were illegal the risks were substantial.

A logging elephant hauls a teak log across the Nam Ou river. Photo by Luc Forsyth,

Back at the Luang Prabang camp, we talked with Son Phet about what we had seen. “I’m a bit worried,” he said about the future of elephants in Laos. “We used to be ‘the land of a million elephants,’ but now we’re just a few thousand. They can be valuable, and people sometimes hurt them [while trying to earn money with them]. When I see this I want to tell people to stop so that we can keep elephants in Laos for future generations.”

A mahout leads his elephant back from bathing in the Mekong river. Photo by Gareth Bright.

This piece originally appeared at A River’s Tail.