This is the third in a three-part presentation of Victoria Kim’s multimedia report, created in memory of her Korean grandfather Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), which details the history and personal narratives of ethnic Koreans in Uzbekistan. It was originally published in November 2015 and is republished here with kind permission. Read part one and part two.

***

Fedor Lee in the Soviet army. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Fedor Lee

There is one memory that is especially painful for Nikolay. It is the memory of a very dark night back at home. He was still a very small child.

As a 3-year old, Nikolay could vividly remember everything around him. That night he was peacefully sleeping in his bed, when adult voices suddenly woke him up. Nikolay walked into the living room and saw a crying Korean stranger. He was telling something to Nikolay’s parents who were also crying while listening to him.

Nikolay still cries himself like a small child, telling me this story 60 years later.

He was positioned in Kraskino town and separated from the rest of his family who lived in Crabs. When Stalin’s order for the deportation of Koreans came, he discovered that his whole family had been shipped to Uzbekistan on a train only very shortly before his own arrest.

As a soldier, Fedor Lee was under an even higher level of suspicion and scrutiny than the rest of the Koreans. According to the official version, he was accused by his neighbors of being a Japanese spy, declared a traitor and an enemy of the Soviet state.

Fedor was condemned to ten years of forced labor in the Siberian gulag in Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. He did not last even through the first half of his imprisonment.

Every day they were sent to cut lumber deep in the Siberian woods, in spite of freezing temperatures, lack of warm clothes and malnutrition. Fedor badly injured his legs while cutting a tree, and in the cold weather developed gangrene. Even though he was unable to walk, Fedor’s comrade would remember, they still had to take him out to their working station, where he would cut branches from fallen trees.

After he got so weak that he could not work any longer, the prison guards shot him. It happened in the early 1940s, and nobody really knew where his body had been buried.

The comrade, whose name we will never know, fulfilled his promise to Fedor. He found Fedor’s family and came all the way to Uzbekistan to tell them everything that had happened.

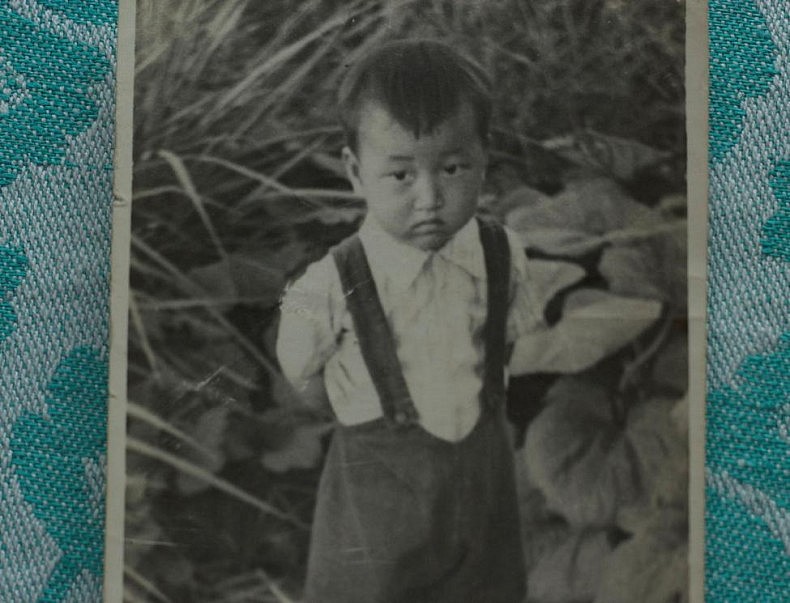

Alexey’s first son Leonid – one of the only photographic memories left of Alexey Ten. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Alexey Ten

It seems that in the lives of some there can never be too much suffering.

The lives of two generations–Nikolay’s grandparents and parents–bear clear signs of two waves of repressions against the ethnic Koreans and political prisoners of the Soviet state between the early 1930s and late 1950s.

There is, however, one more story left to tell. One more wave of repressions left to recount. This is one of – if not the most – secretive part of history in the lives of Soviet Koreans. This is the story not so many people happen to know about.

A secretive wave of repressions against Soviet Koreans in the DPRK (from the materials at the US Library of Congress)

Alexey Ten came to Uzbekistan on the same cattle train, together with his brother and Nikolay’s father Konstantin. Together they worked in the swampland and later rice fields, and then Alexey went to study in the Chirchiq military academy near Tashkent, where in the early 1950s he was approached with an unexpected order by his higher military command.

The special request came from the young Comrade Kim Il-sung, picked by Joseph Stalin in the indirect stand-off between the Soviet Union and United States over the Korean peninsula, to lead the North Korean communists. In the early 1950s, this stand-off led to the Korean War, which became known eventually in the West as the Forgotten War.

Many Uzbek Koreans from the Chirchiq military academy, together with other Central Asian Koreans, went and fought the Korean War shoulder to shoulder with Kim Il-sung, helping him to liberate North Korea and establish the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).

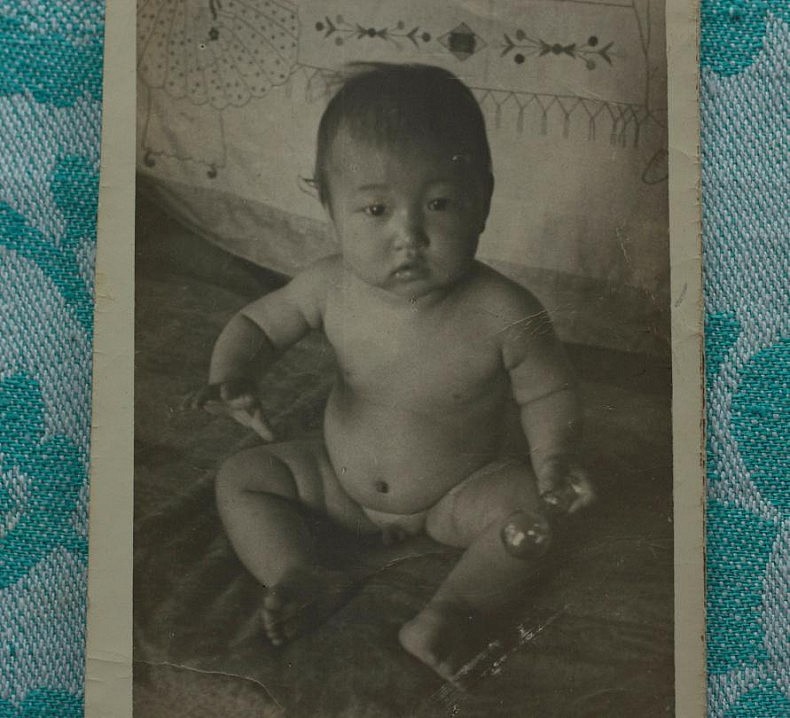

Alexey’s son Leonid or little Lenya. Courtesy of Victoria Ki.

Recognition at Last

Konstantin, Nikolay’s father, must have finally felt very happy for his brother – at last, he was in a very high and powerful position in a country that seemed to highly appreciate him. Earlier and while still living in Uzbekistan, Alexey Ten got married and had his first son Leonid, whom all of his brother’s family felt especially close to.

Later, after Alexey had fought together with Kim Il-sung in the Korean War , his family lived in North Korea. Alexey’s wife got badly ill with appendicitis and was operated on across the border from North Korea in the Chinese city of Harbin, but didn’t survive. Alexey eventually remarried a North Korean woman and had several more children with her; meanwhile his first son Leonid kept living with them in North Korea.

After the direct request from the Comrade Kim Il-sung, he and many other Uzbek Korean war heroes surrendered their Soviet citizenship in exchange for DPRK citizenship. The DPRK seemed to euphorically claim them back.

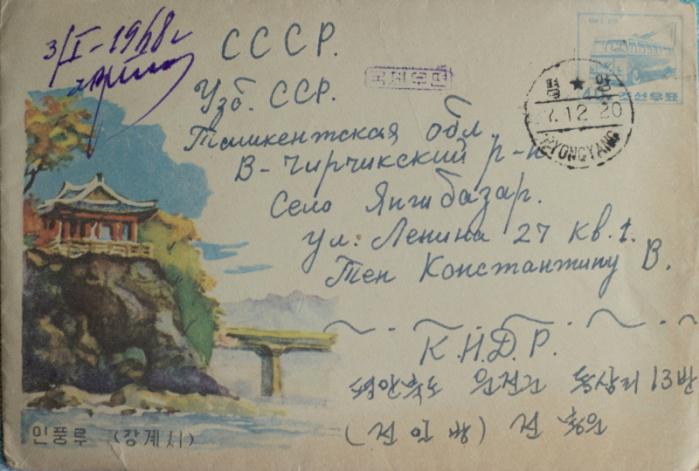

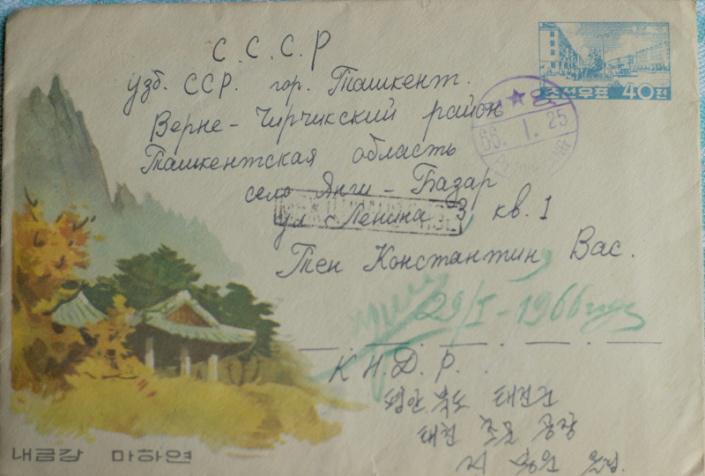

Konstantin, Nikolay’s father, would write to his brother Alexey or his nephew Leonid, always in Korean, and send his letters to the DPRK’s Moscow embassy, which would then pass them directly to General Chon Il Bang (the name Alexey Ten took) in Pyongyang, and vice versa.

Nikolay managed to keep some of the remaining letters, together with the photos of his cousin little Lenya.

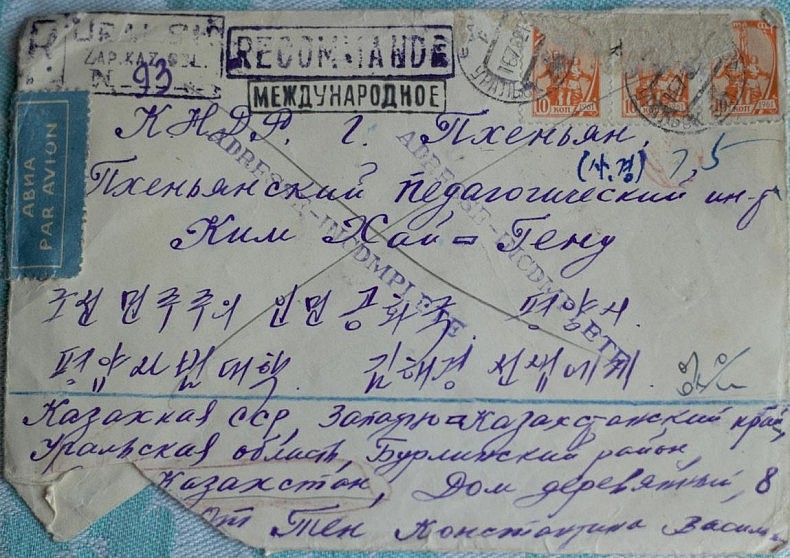

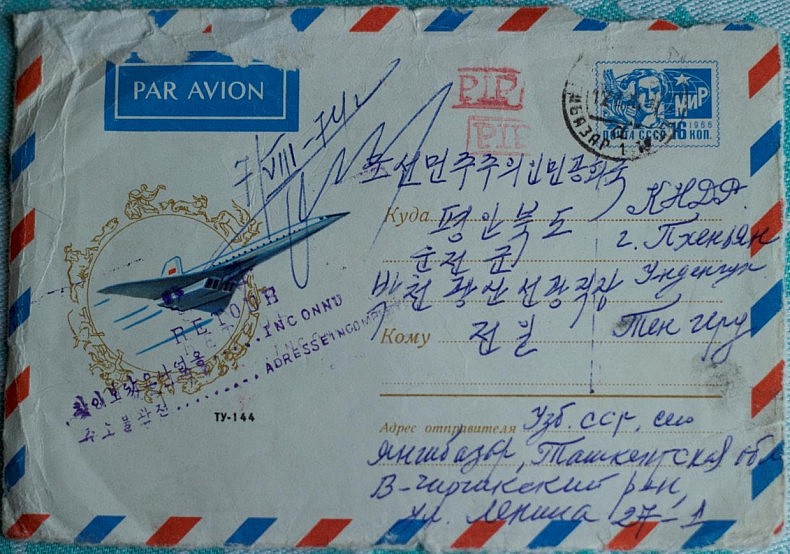

Little Lenya’s postcard from North Korea to his uncle Konstantin. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

A colorful and happy postcard from Pyongyang signed with a trembling hand of the little child in broken Russian, wishing his cousins the best of luck and plenty of health. The lines in Korean from both brothers and little Lenya, who would always write all first names and some particular words in Russian, as if trying not to forget his mother language.

Konstantin’s letter to his brother Alexey in North Korea. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

The signature of the North Korean ambassador in Moscow, stating that he had indeed passed the letters between the recipients.

Those invisible ties that linked the Uzbek Koreans back to North Korea weren’t to last long. Nor was their euphoric success in the DPRK, a historical motherland they were so happy and proud to help rebuild, to be anything but brief.

Konstantin’s letter to Pyongyang, returned with a stamp “Incomplete address.” Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Recipient Unknown

In 1953, upon the death of Joseph Stalin and the demolition of his personality cult as contradicting to the true principles of Leninism, the relationship between North Korea and the Soviet Union started to deteriorate.

Kim Il-sung, who adopted the system of adoration and political reprisals from his own beloved Great Leader, felt vulnerable after Stalin’s defamation in the USSR and started suspecting the new Soviet command of plotting to destroy him in a direct coup d’etat.

Among the first to blame for the same old sins – political and military treason, espionage, and animosity to the DPRK – were the same Soviet Koreans who again and again found themselves between the wheels of ruthless state machinery bound to destroy them.

It looked like Kim Il-sung was trying to change the past and make it seem as if the years between the 1940s and 1960s had never existed. He did everything possible to wipe out the entire memory of the traitors who had given him and their historical motherland everything, up to their own lives.

Suddenly, Konstantin’s letters started returning from the Moscow-based North Korean embassy with a weird stamp: “Recipient unknown.”

Recipient unknown, Konstantin’s letter returned from North Korea. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Alexey’s postal address simply ceased to exist. Nobody could explain anything. Konstantin kept sending letters, and the letters kept coming back with the same postal stamp, “recipient unknown.” This lasted until Konstantin, exhausted and anguished, managed to talk directly to the North Korean ambassador in Moscow, who finally explained everything.

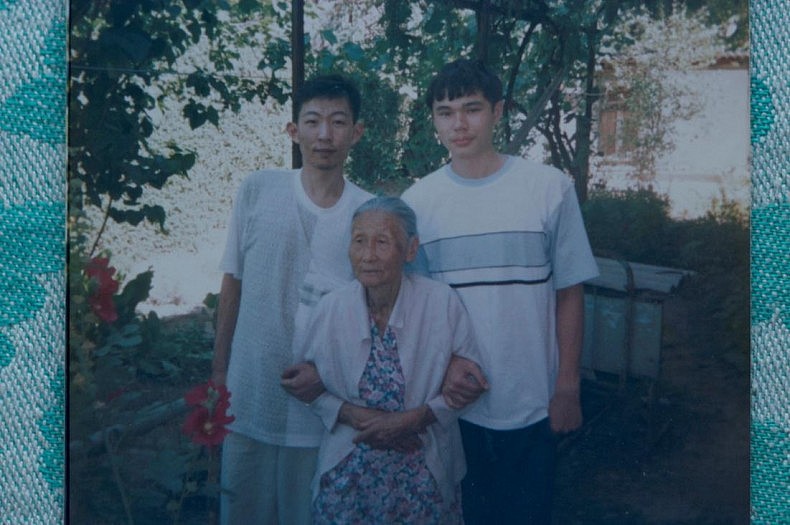

Galina Lee and her grandchildren. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Post Scriptum

How many cycles of repression can one survive? How many tears can one cry? How many family members can one lose? And the most important question – what for and whose fault is it that such atrocities keep happening?

The Soviet Koreans, Uzbek Koreans, Koreans kept spinning again and again, crushed between the wheels of history, betrayed and dishonored again and again by a foreign motherland. How many motherlands can one lose and how many of them can one get?

Lenin medal and certificate book. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

And what is it worth, after all, when at the end the only thing you are bound to be is homeless, forgotten, and dishonored? Nikolay’s parents could never answer those questions. Have they even asked them?

Nikolay answers my question this time. “Have they ever blamed Joseph Stalin or the Soviet state for what it had done to them? Maybe, they did. Probably so. I don’t really know, because they were never free to talk about it, even with us. I don’t blame anyone any longer. I simply hope such atrocities will never happen again.”

Galina Lee with her children – Nikolay Ten and his three sisters. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

Part of the archival photography presented in this report on the Koreans in Soviet Uzbekistan, including several photographs by a distinguished Uzbek Korean photographer Viktor An, were sourced from www.koryo-saram.ru and used in this multimedia project with the permission of the blog’s owner Vladislav Khan.

Please address all comments and questions about this story to [email protected]