On July 12, an arbitral tribunal issued its ruling in Philippines vs. China, the case brought by Manila challenging China’s claims and actions in the South China Sea. While much of the case dealt with the nitty-gritty details of the status of certain features under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) or on the legal legitimacy of “historic rights,” one section veered away from the legal and into the scientific. In addition to evaluating China’s claims, the tribunal has been asked to look at how Chinese activities had impacted the marine environment of the South China Sea.

The tribunal found that “China had caused severe harm to the coral reef environment,” specifically in reference to “China’s recent large-scale land reclamation and construction of artificial islands.” By undertaking such activities, the tribunal ruled that China had “violated its obligation to preserve and protect fragile ecosystems and the habitat of depleted, threatened, or endangered species” and “inflicted irreparable harm to the marine environment.”

The tribunal’s comments on environmental issues, like much of the rest of the ruling, directly contradicted numerous statements from the Chinese government.

On June 16, 2015, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lu Kang told reporters, in no uncertain terms, that China’s “construction activities” on the Spratly Islands had not and would not “cause damage to the marine ecological system and environment in the South China Sea.”

Earlier, on April 28, 2015, another Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Hong Lei, had rejected the notion that China’s island-building was harming the environment. “China’s construction projects have gone through years of scientific assessments and rigorous tests, and are subject to strict standards and requirements of environmental protection,” Hong said. “Such projects will not damage the ecological environment of the South China Sea.”

In its ruling, the tribunal noted that it had asked China to provide its environmental assessment studies, which are required by Article 206 of UNCLOS. China, which refused to participate in any capacity in the case, did not comply. To date, none of the “scientific assessments” referenced by numerous Chinese officials have been made public.

A year later, on May 6, 2016, Hong went into more detail about the process. During its construction in the Spratlys, Hong explained:

China takes the approach of ‘natural simulation’ which simulates the natural process of sea storms blowing away and moving biological scraps which gradually evolve into oasis on the sea. The impact on the ecological system of coral reefs is limited. Once China’s construction activities are completed, ecological environmental protection on relevant islands and reefs will be notably enhanced and such action stands the test of time.

That explanation was flatly rejected by John McManus, professor of marine biology and fisheries and director of the National Center for Coral Reef Research at the University of Miami. McManus, speaking at a conference on the South China Sea held at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)in Washington DC on July 12, said China’s process for constructing its islands has “nothing to do with the natural reef island building process.”

Between the dredging and island building, he added, China “kills basically everything.”

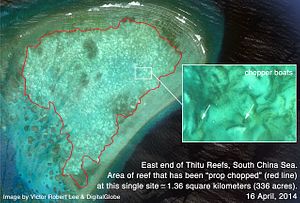

However, while construction is a problem, it pales in comparison to the damage done by the illegal harvesting of giant clams. As National Geographic explains, the poachers “use boat propellers to loosen the valuable bivalves” – in the process destroying the coral reefs surrounding the clams. China’s island-building may have grabbed the headlines, but these illegal fishing practices have caused more environmental destruction. According to McManus’ figures, Chinese dredging and island building activities have damaged or destroyed 55 square kilometers of reef; the destructive methods of giant clam fishermen have destroyed 104 sq km of once-living coral.

The irony, McManus says, is that China can correctly claim it “only built on dead coral” when constructing its islands – because the coral had already been destroyed by giant clam fishermen. And many of those fishermen are Chinese, based in Tanmen village on Hainan Island.

In an article for The Diplomat earlier this year, Zhang Hongzhou writes that the giant clam industry began booming in 2013, when the Chinese government decided to turn a blind eye to the illegal harvesting of a protected species in order to bolster its claims in the South China Sea. “By 2015, Tanmen’s giant clam industry was supporting nearly 100,000 people, according to estimates,” Zhang writes.

The arbitral tribunal also determined that the Chinese government was responsible for the poaching – and the ensuring devastation of coral reefs. The tribunal ruled that “Chinese authorities were aware that Chinese fishermen have harvested endangered sea turtles, coral, and giant clams on a substantial scale in the South China Sea (using methods that inflict severe damage on the coral reef environment) and had not fulfilled their obligations to stop such activities.”

Damningly, the tribunal even suggests that fishermen were allowed to harvest the clams on features where China would soon be building, precisely because Beijing was aware those reefs would soon be devoid of life:

The Tribunal finds that China, despite its rules on the protection of giant clams, and on the preservation of the coral reef environment generally, was fully aware of the practice and has actively tolerated it as a means to exploit the living resources of the reefs in the months prior to those reefs succumbing to the near permanent destruction brought about by the island-building activities.

Victor Robert Lee came to the same conclusion in an analysis of satellite imagery for The Diplomat in January, noting that “[C]ontroversial land-filling operations by China at Fiery Cross, Subi and Mischief reefs in 2014 and 2015 were immediately preceded by waves of chopper boats cutting their arc patterns across wide areas of the reefs.”

Last year, China began cracking down on the giant clam trade, officially banning the harvesting, transportation, and sale of giant clams. But that may be too little, too late. According to Edgardo Gomez, professor emeritus and National Scientist at the Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, giant clams have been “virtually wiped out” in the South China Sea.

The amount of environmental damage could have devastating consequences for the people of all the countries surrounding the South China Sea. McManus predicts a “major, major fisheries collapse” if decisive action isn’t taken. Current activities are “destroying the fish production machine,” he says.

Kwang-Tsao Shao, research fellow and executive officer at the Biodiversity Research Center of Academia Sinica in Taiwan, raised one a possible solution at the CSIS conference: establish marine protected areas around each feature in the South China Sea. McManus proposed a multilateral agreement to protect the marine environment, with the Antarctic Treaty as a possible model.

The problem, of course, is that the features – and waters surrounding them remain disputed. That lends a political coloring to any potential environmental actions. It would also make negotiating and administering multilateral environmental regulations extremely difficult. Meanwhile, each country’s separate regulations aren’t getting the job done either. If one country creates a fishing regulation, McManus explains, “other countries feel obligated to violate it” so as to avoid tacitly recognizing another state’s jurisdiction over the area.

In his presentation at CSIS, Gomez called the South China Sea a “marine paradise” – home to what the arbitral tribunal called “highly productive fisheries and extensive coral reef ecosystems, which are among the most biodiverse in the world.” That environment is now in crisis.

In May, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong told reporters that “China cares about protecting the ecological environment of relevant islands, reefs, and waters more than any other country, organization, or people in the world.” In its ruling, the tribunal found otherwise. And though China has sworn to ignore the ruling, it would be wise to pay attention to the warnings of the scientists who testified before the tribunal, and those who spoke at CSIS. If a “fisheries collapse” is indeed in the cards, China – which consumes more fish than any country in the world — will suffer immensely.