Before South Korea’s conservative presidents severed ties with North Korea from 2008, their liberal predecessors Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun promoted peaceful engagement and rapprochement, an approach called the “sunshine policy.” The name stemmed from an ancient Greek fable where the wind and the sun competed to remove a man’s cloak. No matter how strongly the wind blew, the man only wrapped his cloak more tightly to keep warm. But when the sun shone, the warmth made him take his cloak off. The wind symbolized unsuccessful coercive policies toward North Korea and the sun stood for an approach able to persuade North Korea to take off its anachronistic and uncomfortable cloak, changing at last. It wasn’t a “leftist” policy, as it was labeled by critics from the right, since South Korea’s strongman President Park Chung-hee had tried a similar policy in the 1970s.

The critics called Kim and Roh’s North Korea engagement “checkbook diplomacy,” an expensive flop, and considered both presidents as either naïve, striving for fame, or having a sinister agenda to strengthen North Korea’s regime. An influential American journalist gave his book the title Korea Betrayed: Kim Dae-jung and Sunshine. And “sunshine” even became a term of mockery. In addition, the opponents of engagement cited North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006 as an irrefutable proof of the complete failure of the sunshine policy. To North Korea, it meant dissuasion and a bargaining chip in negotiating with Washington as the George W. Bush administration “reversed the age of warm sunshine back to the age of cold wind,” which made North Korea abandon the non-proliferation treaty, oust International Atomic Energy Agency inspectors, and start testing long-range missiles, Kim Dae-jung explained in a speech at Harvard University.

Kim had indeed a very ambitious plan to decrease inter-Korean tensions and work toward a peaceful reunification. The Korean War still lingers, as only an armistice was concluded in 1953, not a peace treaty. Kim was aware of the fact that Pyongyang couldn’t and wouldn’t change quickly and that he wouldn’t get much gratitude for his efforts either. A transformation of North Korea similar to the transformations of China and Vietnam, which brought about significant changes after the West normalized relations with them, wasn’t just around the corner.

The tool to further Kim’s agenda was the set-up of a wide cooperative framework that included infrastructure development, such as the restoration and construction of roads and railways, economic assistance, as well as a wide variety of inter-Korean business ventures. It was aimed at both increasing living standards in the North and upping its dependence on the South. More than 40 different types of agreements were concluded between the two Koreas during this period. South Korean companies were not only permitted but actively encouraged to interact with the North; in many cases they benefited from subsidies. South Korean firms became involved in the North in mining, agriculture, tourism, car manufacturing, and textile production. The most outstanding achievement of Kim Dae-jung’s policy was an industrial park in the North Korean city of Kaesong, where more than a hundred South Korean companies employed more than 50,000 North Korean workers until South Korea’s current President Park Geun-hye pulled the plug in 2016 and buried the last remnants of “Sunshine.”

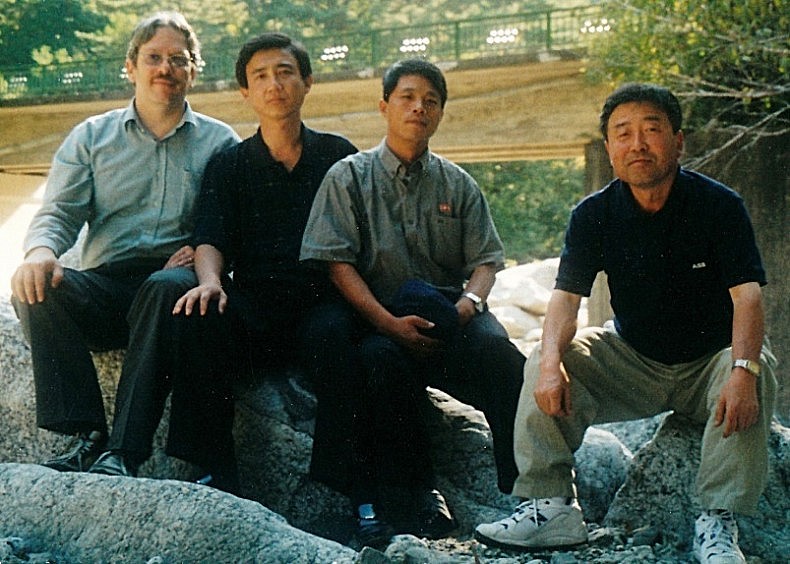

Relaxing under the “Sunshine”: South and North Korean businessmen and Felix Abt outside Pyongyang after strenuous business meetings. Image courtesy of Felix Abt.

I lived and worked in North Korea both when the sunshine policy peaked and when it faded away. As I was also involved in North-South projects I experienced up close how it played out.

As resident country director of the ABB Group, a global leader in power technologies, I participated at a trade fair in Pyongyang where we exhibited an innovative, environmentally-friendly large transformer for utility and industrial applications. The transformer was made in an ABB-factory in South Korea. This triggered lively discussions with North Koreans, who were interested in transferring at least part of the factory in the South to the North, from which transformers could be sold to the South, China, and elsewhere.

As CEO of North Korea’s first foreign-invested pharmaceutical enterprise I explored ways to sell Northern traditional herbal medicine in the South. I examined the possibility of setting up up a small processing unit at the Kaesong Industrial Park from which to distribute the products southward. Our North Korean company co-owners liked the plan. Yet we were ahead of the times — though the South Korean medicine wholesalers and retailers I talked to found the idea intriguing, they cautioned that marketing would become a costly endeavor as Southerners would not trust that medicine from the North would be safe.

The CEO from a large South Korean construction company invited me to Seoul to help him draft a plan to get sand, scarce in the South but abundant in the North.

The former CEO of South Korea’s largest dairy firm wanted me to help him set up a dairy business in the North. Many members of this cooperative were farmers of northern descent and enthusiastically supported the idea. It was a commercial project with a humanitarian component: Koreans and other donors around the world pledged to sponsor a daily glass of milk for every North Korean child.

I was also leading the negotiations between North Koreans and a large South Korean chaebol (business group) on a water project on Paekdu, a “holy” mountain shared by North Korea and China and revered by the surrounding peoples throughout history. Both the North and the South Korean interlocutors were convinced that the magical natural water from Mount Paekdu (to be sold as is or carbonated or as drinks blended with fruit juice or artificial flavors) would become a huge commercial and PR-success.

“Sunshine” made it possible: South Korean lawmakers, visiting a trade fair in Pyongyang, meet up with Felix Abt and his North Korean staff at their booth. Image courtesy of Felix Abt.

Negotiations were not easy. The mistrust between the North and South Korean business partners was an important obstacle to business development. While the Northerners suspected Southerners of having a hidden agenda to make a hostile takeover, the Southerners feared the Northerners were out to rip them off. Both sides seemed to have trusted a neutral Swiss businessman more than their fellow Koreans. Still, the chairman of one of South Korea’s largest law firms once asked me bluntly: “On which side are you?” “On my side!” I retorted.

To my surprise, I soon had to face one big anomaly, namely that the input costs (rent, salaries, electricity, etc.) for South Koreans businesses were substantially higher than for European and Chinese businesses. I disagreed with this discrimination and raised the issue with the authorities who replied, “The Southerners helped destroy our country, that’s why they have to pay a higher price.”

I wanted to understand the reasoning behind this attitude and asked a history professor at Kim Il Sung University who explained to me:

Unfortunately, Northerners have often been mistreated by Southerners throughout our common history. Southerners helped foreigners exploit the North’s riches and the North’s people, forced Northern women into prostitution in the South, forced Northern men to fight Southern kingdoms’ wars and more recently helped Japan colonize our country and supported the United States to destroy our cities and dams and other infrastructure during the Korean War. They can’t get away without paying any compensation.

That also made me understand why Kim Dae-jung transferred hundreds of millions of dollars to North Korea, which was called corruption by his detractors, before the historical first meeting between a North and a South Korean leader.

During the Sunshine years, not only more and more business people from the South came to the North. NGOs, artists, religious groups, and tourists also crossed the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Close to two million South Koreans visited scenic Mount Kumgang. More than 20,000 South Koreans also met there with their Northern family members. An old North Korean told me he was never as happy in his life as when he met his Southern family, torn apart during the Korean War, at Mount Kumgang.

Every day, about 400 South Korean vehicles crossed the DMZ, which Bill Clinton called the most dangerous place on earth, to North Korea. About 1,000 people entered the North on a daily basis. In 2008 North Korea even decided to allow South Korean visitors to use their own cars to make the trip.

Most of the visits which now had become commonplace were limited to mount Kumgang, Kaesong, and Pyongyang. But more and more South Koreans were visiting other parts of the country, in particular when they were involved in agricultural projects. Of course, they were watched and controlled, but they also learned a lot as they could understand Korean and, more importantly, they played the role of ambassadors representing the rich, imitable South Korea in North Korea’s impoverished hinterland.

This was also a time when North Korean officials started admitting that mistakes have been made in the past and interaction with the outside world to help improve things was welcome. Sunshine allowed North Korea to see a future beyond Kimilsungism, its state ideology.

I watched my staff and other North Koreans observe Southern visitors. They tried to do so discreetly, but couldn’t always suppress their amazement with an open mouth or a spontaneous smile. Southerners were well dressed, looked well fed and healthy, and were tall by Northern standards. They brought the latest cameras with them, were relaxed, and showed self-confidence. Their appearance must instantly have neutralized the North’s propaganda myths of South Koreans oppressed by the U.S. imperialists and their South Korean puppets.

It was also interesting for me to observe when North Korean and South Korean business people interacted outside the formal setting of business meetings — in karaoke rooms for example. Singing together, holding hands, and even hugging one another (and sometimes getting drunk and very emotional together) wasn’t choreographed. The encounters transcended politics and showed me Koreans on both sides of the fence as human beings who could get along very well if politics did not stand in their way.

In December 2007, South Koreans were disenchanted by what they perceived as a liberal president’s failed domestic economic policy (not related to “Sunshine”). They elected Lee Myung-bak, a businessman from the conservative opposition party as president, thinking he could fix their woes. Lee had previously made an impressive career in the construction industry and was nicknamed “bulldozer.” He had been an opponent to “Sunshine” and when he took over the presidency in early 2008 he quickly started bulldozing what his predecessors had built up.

Shortly after his election I went to a meeting with North Koreans working on a North-South project. I explained that it would be a waste to continue to work on the project given the new political circumstances. I must have shocked them with bad news that hadn’t reached them yet. It was the first time I looked into so many genuinely disappointed and sad North Korean faces. With Sunshine gone, the smiles were gone too.

Felix Abt is a serial entrepreneur who has lived and worked in nine countries on three continents. He is the author of the book A Capitalist in North Korea: My Seven Years in the Hermit Kingdom.