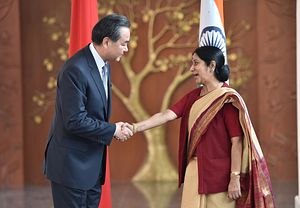

The upcoming G20 summit provides China a unique chance to chance to demonstrate China’s “good intentions” as a responsible stakeholder. To facilitate the summit, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited India over the weekend for strategic communications with Indian side. According to Wang, China and India reached an important consensus that both states should firmly support each other in hosting the upcoming G20 Summit in Hangzhou, China and the BRICS Summit to be held in Goa, India.

China, like many other developing states, desires to portray itself as “responsible power” through various international platforms. Among the many international bodies, the G20 and BRICS are of special significance given their role in a constructing a multipolar world order that gives the developing world more of a voice. China was awarded of the presidency of G20 at the closing of the G20 Brisbane Summit in 2014. This will be the first time that China chairs the world’s “premier forum for international economic cooperation.”

On the one hand, for the Communist Party of China (CPC), hosting the G20 summit will be a valuable chance to strengthen its legitimacy domestically, given China’s decelerated GDP growth, widening income gap, and the rising public pressure for “political reform,” which the CPC government resists. On the other hand, the G20 will be an important platform for China to attract world attention and to showcase China’s “responsible” image around the world. Through actively attending the newer established forums such as G20 and BRICS, China is both seeking changes to the “traditional” global economic governance model, centered upon the Bretton Woods Institutions, and experimenting with new processes such as the BRICS forum and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

Given the importance of the event, Beijing has spared no effort in preparations. Domestically, China has spent nearly $100 billion (according to the budget reports from China’s Foreign Ministry, Ministry of Commerce, and Ministry of Finance) for stadium construction, international business trips, security arrangements, and urban renewal. Internationally, China has to win international support for the G20 Hangzhou summit in order to avoid having “critics” from other G20 members harm China’s image, both internationally and domestically.

As a member of G20, India is viewed by China as a competitor in regional and international platforms, both economically and politically. The most sensitive issue between China and India in the G20 would be the South China Sea. India insists, especially under the Narendra Modi government, on upholding the principle of “freedom of navigation and commerce” in South China Sea, a position it shares with the United States. India has even been viewed by Vietnam and the Philippine as an important ally to resist China’s territory claims in the South China Sea.

China believes that some Western states, especially the United States, may seek to talk about the South China Sea at the G20 summit to embarrass China, especially after the South China Sea arbitration ruling in July. Against this backdrop, it is necessary for China to win a promise from India not to talk about South China Sea in the upcoming G20 summit. To that end, China has implemented the diplomatic equivalent of the “carrot and stick” approach against India. Wang’s comments made during the trip to India contained a certain amount of menace. Wang linked the Hangzhou G20 summit with the upcoming Goa BRICS summit, suggesting China may adopt an “eye for an eye” strategy toward India: if India raises the South China Sea issue at the G20 summit, China would take “revenge” on India during the Goa BRICS summit. As for the carrot, Wang promised to support Indian membership in the the Nuclear Suppliers Group in return for India’s promise to not talk about the South China Sea during the G20 summit.

However, the “carrot and stick” maneuver adopted by China may be not able to guarantee India’s silence on the South China Sea issue during the G20. On the one hand, China’s “stick” seems useless. Although Wang hinted at an “eye for an eye” tactic, in truth China could not bear the cost of a rupture at the BRICS summit, which has been viewed by China as an important chance to enhance its “international positive image” around the world. Actually, China lacks an effective means to check India’s vital interests. Although India needs China’s help over the Kashmir clashes with Pakistan, China needs more cooperation from India, in areas ranging from the Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang issues to counterterrorism.

On the other hand, China’s “carrot” for India does not seem very attractive. India desires to be an elephant, not a rabbit. Joining the Nuclear Suppliers Group is important for India’s great power ambition, but given the limited international support for China’s South China Sea claims, it is very likely that India’s leader will talk about the South China Sea during the G20 summit once the United States or other states mention the topic. For India, the South China Sea issue is an important chance to unite a regional alliance against China’s expansion under the “One Belt, One Road” policy. Meanwhile, India’s growing perception of China as a threat is driving New Delhi to strengthen military ties with some U.S. allies and associates in the Asia Pacific region, including Australia, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam.

As it has been a hot topic in the Asia-Pacific region, the South China Sea issue will surely be mentioned and discussed during the upcoming G20 summit held by China in Hangzhou. Although China tried to ensure India’s silence on the South China Sea issue with a “carrot and stick” approach during Wang’s visit China actually lacks effective means to keep India silent. It is unlikely that India will keep quiet over the issue as China wishes.

Wang Jin is a Ph.D. candidate at the School of Political Science, University of Haifa, Israel. Wang is also a part-time research fellow at the Middle East Studies Center, Xiamen University, China.