In the 1970s, foreign aid attracted criticism for not promoting sustainable development; the call was for trade not aid. Nearly 50 years on, academic and policy discord continues unabated. For instance, in 2009 Dambisa Moyo, a Zambia-born international economist, wrote a stinging indictment of foreign aid, describing it as “dead aid.” More recently, Angus Deaton, the 2015 Nobel economics prizewinner argued that “most overseas development aid is a waste and even destructive use of money” as it acts to undermine the development of local state capacity. Instead, the imperative should be to promote self-sustaining development through policies that stimulate growth, including infrastructural improvement, educational investment, technical support, and greater trading access into rich country markets.

Deaton’s authoritative judgement should concern Western electorates because of the huge monies they disperse on foreign aid. According to OECD data, the United States and Japan were the world’s two most generous aid givers in 2015, spending almost $32 billion and $10 billion, respectively. Similarly, British taxpayers would likely feel vexed at the notion that their country’s aid ($19bn) is destructive rather than constructive, not least because the Tory government is presently engaged in an explosive expansion of foreign aid, with a spending level that now almost exactly mirrors the chancellor’s £12bn austerity measures following the 2007-08 global economic and financial crisis. Britain’s ring-fenced foreign aid spending since that time has accelerated from £5.2bn to the present £12.2bn, and is scheduled to continue to grow by 24 percent to hit £16.3bn by 2020, exceeding the projected Home Office budget. Indeed, U.K. aid generosity knows no bounds: the country spends nearly 20 percent more than Germany (Europe’s largest economy); twice the sums pledged by France and Japan; is the world’s second biggest donor in absolute values after the U.S. (though the latter’s relative contribution represents merely 0.19 percent of its GDP); and easily fulfills its global 0.7 percent commitment, just one of only five countries to do so (all others being Scandinavian).

Reportedly, six out of ten Britons have concerns over aid — not just its scale, but also its implementation, following a constant drip-feed of disconcerting revelations that have eroded public confidence. Despite the Department for International Development Aid’s (DFID) claim that value for money is the primary objective, the U.K.’s ballooning aid budget has faced criticism for targeting non-development activities (English lessons for Uruguayan footballers and for personnel who work on TV game shows in Ethiopia), funneling aid to emerging mega-economies (India and China), spending hurriedly (£1bn in two months in order to achieve the 0.7 percent target), and also uncontrollably (aid reportedly ending-up supporting terrorist activities).

With the passage of time, Brexit may increase the U.K.’s direct control over its aid spending, but currently a sizable 37 percent of the country’s aid is “lost” because it is dispersed through multilateral organizations, and often wasted on inappropriate projects, due to lack of oversight and transparency, corrupt practices, inefficient management and implementation. Such wastage is recognized, though, and the U.K. plans to reduce aid funding to UNESCO, where staff salaries swallow a remarkable 50 percent of its annual £560m budget, and to the European Commission in the run-up to full Brexit. In Europe, flaws were laid bare by a 2015 EU Budgetary Control Committee Report, which stated that over 900 aid projects worth £11.5 billion were at risk of failing to achieve their objectives, or incurring serious delay. It seems that around half of the EU’s annual £23 billion development aid budget has missed its target, or as the Report cryptically put it: “Every second Euro spent by the EU does not achieve what it pays for.” The Report’s German chairwoman was graphic in her description of aid, asserting that the money is being “thrown down the toilet.”

Such problems are likely behind recent declines in the aid budgets of 12 of the world’s biggest donor countries, including the United States (cuts of $2.3bn or 7 percent in 2015-16), Australia (cuts of $761 million or 20 percent in 2015-16, and $170mn or 7.4 percent in 2016-17), Canada, Finland, France, Holland, Ireland, Japan, Poland, and Spain. By contrast, the U.K.’s aid spend continues to accelerate.

In the U.K., a 2015 aid policy review recommended strengthening the link between aid and national interest, as well as broadening the definitional scope of aid to include refugees, humanitarian crises, climate change, peacekeeping as well as other broader security issues. These reforms would translate into around 28 percent of U.K. aid being dispersed by government departments outside DFID by 2020. The impact of such changes is presently unclear, but the obvious danger is that development per se will cease to be the core objective of foreign aid. Rather than dilution of the development objective, perhaps a rethink of Western strategy is required, whereby the fundamental tenets of aid policy are re-examined.

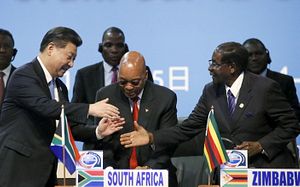

Is there an alternative path? Perhaps, controversially, China’s radically different aid model is worth consideration. The model contradicts just about every tenet of the Western approach, and hence attracts near-universal opprobrium, but is nevertheless arguably more effective in achieving its development goals. Stripped of ideological preconceptions and prejudices, the model offers a coherent economic diplomacy framework for promoting the development of underdeveloped states whilst simultaneously sponsoring China’s national interest. Beijing’s aid strategy targets poverty reduction, principally through improvements in agriculture, education, health services, and welfare facilities.

Beginning modestly in the 1950s, aid flowed to North Korea and Vietnam for political purposes. Later, Deng’s 1978 “opening up” policy paved the way for the Tenth Five Year Plan’s (2001-05) unequivocally economics-driven “going out” strategy, linking overseas aid to Chinese investment opportunity. Although the Tenth FYP merely encouraged “going out, actively and gradually,” the Eleventh FYP (2006-10) referred to “going out further” and the Twelfth (2011-15) to the need for “speeding up implementation of the going out strategy.” Presently, China’s 28 strategic sectors have cultivated over 160 flagship multinational enterprises that benefit from commercial contracts via foreign aid projects, especially in Africa. Investment is focused on profitable enterprise, aimed at sectors of “mutual” national economic security concern, such as food, energy, and minerals.

China’s complementary investment and aid model has four broad attributes. First, there is an emphasis on China’s “South-South” credentials, particularly the importance of equality, common development, and a “partnership of equals,” reflecting what is held to be a “win-win” development equation. This approach is based on aid-trade-investment deals leveraging donor-recipient synergy and mutual benefit. On the one hand, aid is a mechanism for fostering self-reliant development among low-income developing states, while on the other, it aims to ensure an unfair burden is not placed on donor country citizens. Aid is thus not altruistic, but rather a crucial strand of Chinese soft power. The world’s second biggest economy, China, is uniquely positioned as a developing country (with 82 million citizens mired in poverty) to offer valuable real-time development insights to shape appropriate and effective aid policies in fellow developing states.

The second major characteristic of Chinese aid is that it comes with no “strings attached.” The foundations for this approach lie in the country’s Five Principles for Peaceful Coexistence (including non-interference), as expounded at the 1955 Bandung Conference for non-aligned states. Beijing’s non-alignment banner is strengthened by its non-imperialistic and non-colonialist past and reflected through its current non-interventionist foreign policy. The resulting “Beijing Consensus” lacks recourse to conditionalities, is imbued with a less moralizing tone, and is characterized by a respect for self-determination and national sovereignty. This contrasts starkly with the West’s paternalistic embrace of the “Washington Consensus,” whereby aid is contingent on recipient nations agreeing to capitalist free market principles and democratic reforms, especially good governance and human rights.

The third feature of China’s aid model is that it is almost entirely bilateral, thereby retaining control over how monies are spent. State-to-state aid allows Beijing to retain ownership of the tendering process, such that prime contractorship is awarded to Chinese companies, with the preponderance of procurement sourced from Chinese supply chains. This emphasis on national interest is balanced, however, by Beijing’s insistence that aid ‘directly’ impacts on development via sectoral biases targeting agricultural, mineral extraction, transport infrastructure and, more recently, manufacturing, as opposed to the ‘indirect’ western donor predilections for improvements in gender equality, human rights, transparency and empowerment.

The fourth attribute of China’s aid model is that while it covers grants, interest-free loans, and concessional loans, separately there is a full spectrum of wider “Other Official Funding” economic diplomacy initiatives undertaken by a plethora of government departments, including commerce, agriculture, international affairs and defense. For instance, between 2010-12 China provided technical and on-the-job training for almost 50,000 people from poorer countries, including the provision of around 300 training programs for around 7,000 agricultural officials. Additionally, Beijing’s health diplomacy drive supported the transfer of 3,600 Chinese medical personnel to 54 countries to treat almost seven million patients. China also engages in international disaster prevention and relief efforts, assigning more than 30,000 peacekeepers to nine countries/regions, including Afghanistan, Haiti, and, most recently, South Sudan.

The West’s concern is that China’s $9bn overseas aid (and investment) operates as a form of 21st century neocolonialist imperialism, exploiting poorer states’ energy and commodity sectors. However, this is contested by a growing body of empirical evidence that suggests Chinese aid is allocated irrespective of whether recipient nations are resource-rich, or not, acting to dispel fears that China delivers only “rogue aid” (opaque, political, and exploitative) to “rogue states” (authoritarian and corrupt).

Given the above considerations, President Xi Jinping’s 2015 announcement of a three-year $60bn aid package for Africa presages still deeper Chinese soft power forays into this strategically important continent, and arguably represents a wake-up call for the West that size is not the sole, nor even the main, criterion for effective foreign aid.

Professor Ron Matthews is a defense economist, holding the Cranfield University Chair in Defense Economics at the UK Defense Academy.

Xiaojuan Ping is a Research Assistant at the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore.

Dr. Li Ling teaches at Chinese Military Economics Academy, based in Wuhan, China.