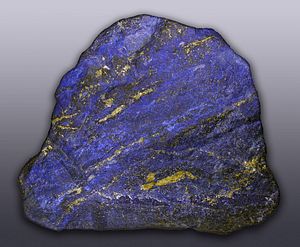

Afghanistan’s northeastern province of Badakhshan used to be one of the country’s more stable regions. But in the last couple of years, the security situation has worsened considerably as armed groups, including the Taliban, have vied for control of centuries-old lapis lazuli mines. The valuable semi-precious stone, once prized by Pharaohs and Renaissance artists, is reportedly smuggled to Pakistan, where much of it is bought by Chinese gem traders, providing a significant source of funds for the insurgents.

A recent investigation by Global Witness revealed that illegal mining of lapis last year contributed about $4 million to the Taliban’s war chest. The anti-corruption watchdog believes the takeover of the mines by armed factions has cost the government tens of millions of dollars in lost revenue. Between 2014 and 2015, it estimates that the illegal trade in lapis was worth about $200 million. Last year the government banned mining of the stone, but this has done little to deter the Taliban and other militant groups. Afghanistan now has a thriving illicit market and the scale of the problem was highlighted in June when security forces seized 65 trucks laden with lapis.

The Global Witness findings reflect the difficulties facing the Afghan extractive industry in general. The country is estimated to have $1 trillion of untapped oil, natural gas, and mineral wealth, including vast reserves of gold, iron ore, copper, and rare earths. In 2010, the New York Times cited an internal Pentagon memo saying Afghanistan was poised to become the “Saudi Arabia of lithium,” an important element in electronic devices. But continued instability has put off many foreign mining companies and is said to have left up to 10,000 mines outside government control. All of this has played into the hands of the Taliban: after the heroin trade, mineral extraction is the group’s biggest source of revenue.

The insurgents appear to have exploited the vulnerability of the mines and the sector’s administrative weaknesses. In April 2015 a report by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), the U.S. government’s leading oversight body, was critical of American efforts to help build a well-regulated extractive industry, saying that the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum lacked “the technical capacity to research, award, and manage new contracts without external support.” Later that year, the then-minister of mines and petroleum, Daud Shah Saba, admitted as much, telling Bloomberg, “Unfortunately, we have failed to well manage and well control our mining sector.” In 2015, two of the country’s biggest mining projects were reportedly hit by delays over security concerns and contract disputes.

Mining revenues are seen as key to weaning the country off its dependence on foreign assistance. Last year, international donors, led by America, contributed around two-thirds of Afghanistan’s national budget of just over $7 billion. SIGAR notes that the country’s mineral resources could in time raise more than $2 billion in annual revenues. Mining currently generates a fraction of the projected figure, and with a resurgent Taliban, there are concerns that the militants will strengthen their grip on Afghanistan’s mineral wealth.

With just 10,000 American troops supporting Afghan forces, the government would be hard-pressed to secure all the country’s mines, but it appears to be struggling to put in place even the most basic protections. Two years ago it introduced a law to regulate the extractive sector but campaigners say the legislation still lacks a provision prohibiting armed groups or members of the army from benefiting from mining. There are also other important shortcomings, such as the absence of both published data on mining production and revenues and a single transparent system for all extractive payments.

Yet there are some encouraging signs. The international anti-corruption coalition, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, of which Afghanistan is a member, recently said the country had put forward a number of recommendations for improving the governance of its mining industry, which, if implemented, could help to improve accountability. However, it remains to be seen whether the authorities have the political will to implement these reforms. “We don’t want another plan that will sit on the shelf gathering dust,” Acting Minister of Mines and Petroleum Ghazaal Habibyar warned recently.

Afghanistan’s international partners also have a role to play. Global Witness believes Washington has not done enough to tackle the sector’s security problems and weak governance, and suggests that Beijing could help to curb illegal mining by pressing Chinese companies that import lapis to step up supply chain due diligence.

Without such concerted action from the Kabul government and its allies, there is a danger that the mineral wealth, which many see as key to Afghanistan’s development and prosperity, will prolong the Taliban insurgency and fuel corruption, with the country succumbing to the “resource curse” that has blighted so many developing economies around the world.

Yigal Chazan is an associate at Alaco, a London-based business intelligence consultancy.