For decades the term “Japan Inc.” has been synonymous with Japan’s mighty global conglomerates, which run large swathes of the country’s economy. At times, the term has instilled admiration (as an “economic miracle”), in the 1980s even fear (“Japan as Number 1”), but lately mostly pity (see: Sharp, Olympus). Who stands behind this term–Japan Inc.–however, is undergoing rapid change.

De-privatization

This shift can best be described as “de-privatization,” coming in two forms. One is the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) buying of stocks via Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) to the tune of now ¥6 trillion (about $58 billion) a year as of July 29 – on top of its already well-known record buying of Japanese government bonds. More than half of all available Japanese ETFs now are in BOJ hands. This turns the BOJ into a major shareholder in private companies, such as Fast Retailing (Uniqlo) or Advantest, according to the Nikkei, a Japanese business daily.

The other form of de-privatization is the expanding stockholding of public investors, such as Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF) – the world’s biggest such fund. The GPIF alone holds roughly 5.5 percent of Japan Inc.’s market cap, in addition to the holdings of numerous other (quasi-)public funds, such as Post Bank. Prodded by the government, these public investors are rebalancing their portfolios towards more stockholding, meaning their holdings will expand further. Between 2012 and 2015, the GPIF alone has doubled its domestic stock holdings to 23.35 percent of its portfolio.

By July 10, Japan’s central bank had amassed ¥8.59 trillion in ETFs. This amounts to about 1.5 percent of Japan’s stock market cap (TSE first section) and about 2 percent of the BOJ’s total assets. Now that the BOJ has stepped up its ETF buying program to around ¥6 trillion, this number could balloon to 5 percent of total market cap in just about two years. Seen together with the holdings of public investment funds, it is no wild guess to expect that within two years over 10 percent of Japan’s entire stock market will be no longer accessible to private investors.

Crowdsurfing

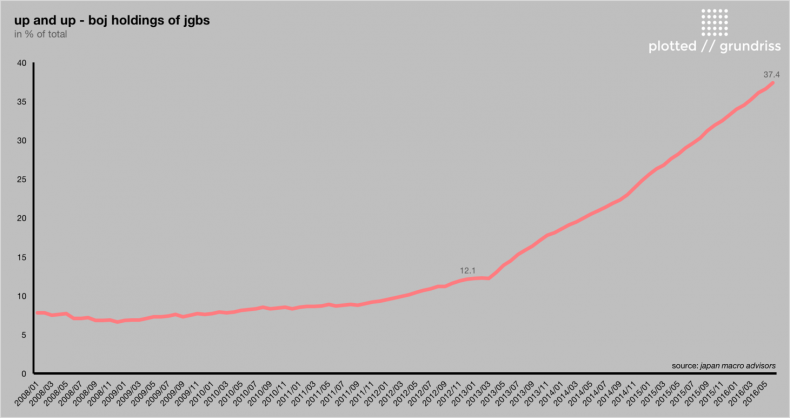

What are the effects of this de-privatization? Two major concerns stand out: first, the inflow of public money crowds out private investors. If this sounds familiar, it is because the same story beginning to unfold in equity markets has been progressing at a much quicker pace in bond markets. Through its program of quantitative easing the BOJ is buying up government bonds (JGBs) and expanded its holding to 37 percent of all outstanding JGBs (see chart below). In 2014, it became the biggest JGB holder.

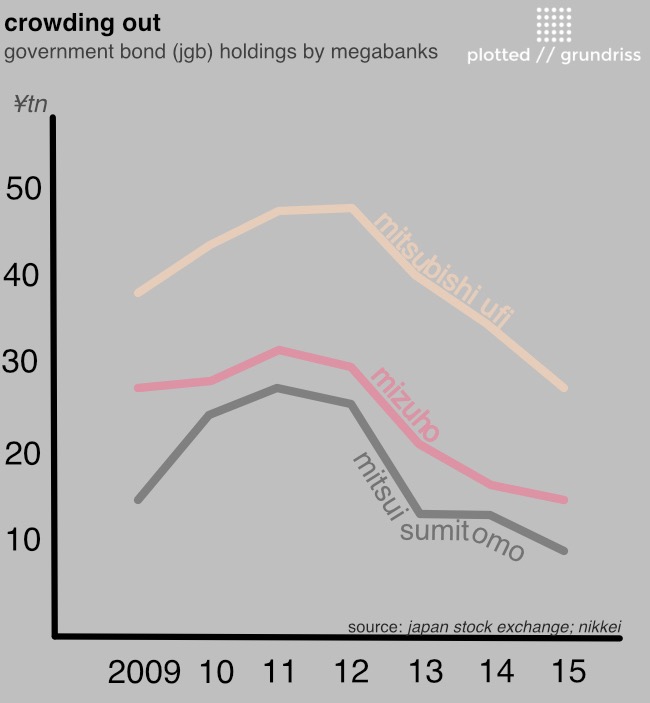

The flipside of this and the accompanying slide in yields is that Japan’s megabanks and major insurers are gradually being pushed out from the bond market (see chart below). This puts them in a tight spot to find stable long-term yields that previously only JGBs and their 30 years or more maturation periods delivered.

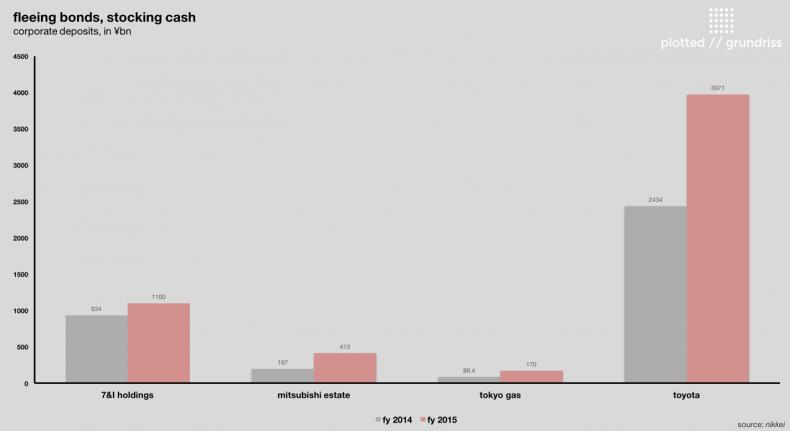

Corporations, too, are being squeezed out from the government bond market and struggle to find places to park their cash. Unwilling to buy newly issued JGBs with negative yields (or to invest in Japan as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe would like them to), firms rather deposit their money. This pushed up total corporate deposits to a record ¥225 trillion in fiscal 2015, up 11 percent from 2014 (see chart below). Toyota alone hoards over ¥1 trillion (roughly $10 billion).

But for many, shifting their assets to riskier stockholdings is unlikely. Insurers’ equity holdings, for instance, rarely exceed about 15 percent of their total portfolio, says Nicholas Benes, representative director of the Board Director Training Institute of Japan. And after the GPIF lost about $50 billion in fiscal 2015 following stock market turmoil, risk-averse pension funds and private households will be in no mood for more adventurous portfolio strategies, either.

Under present conditions in particular, with the stock market near an all-time high, Takuji Okubo, chief economist at Japan Macro Advisors, says, “I wouldn’t recommend anyone to buy Japanese equity right now.” His warning illustrates the tight spot investors find themselves in right now between a dissipating JGB market and a shrinking stock market inflated by de-privatization. One of Abe’s key policy goals — to nudge the wider population to become shareholders — is being undermined by this as well, making it unlikely that Japanese households feel that now is the time to buy shares.

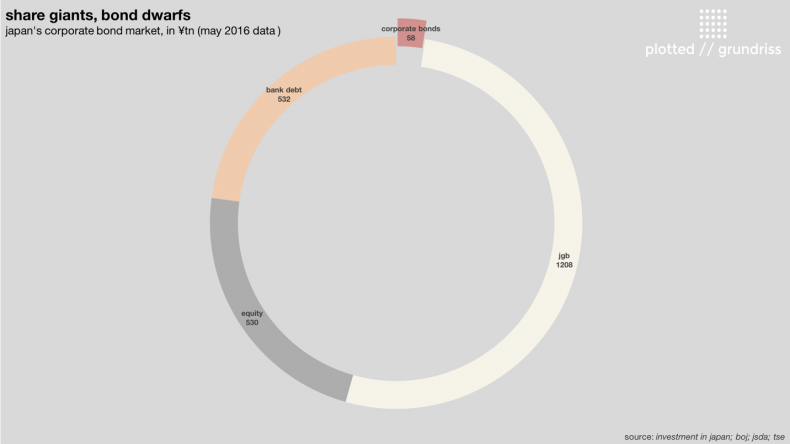

The failure to create a corporate bond market that could offset this tight spot is now coming back to haunt Japanese regulators. At ¥58 trillion, Japan’s miniscule corporate bond market amounts to only 2 percent of the total of Japan’s bonds (JGBs plus corporate), equity, and bank debt market (see chart below). In effect, this leaves many “perplexed” as to what to do other than just hold on tight to cash, says Benes.

Steward Kuroda

It is equally unclear how the central bank’s move into Japan Inc. ownership will affect corporate governance. As ETFs’ low commissions only allow for very limited proxy activism by fund managers, the BOJ’s direct impact on corporate governance is limited for now, says Japan Macro Advisor’s Okubo – particularly as long as the BOJ’s shareholdings are limited to just roughly 1.5 percent of Japan Inc.’s market cap. The GPIF and other public investors are currently still more relevant in this regard. But the quick and as of today accelerated accumulation of Japanese shares in BOJ hands warrants a closer look, since it comes with very unique characteristics.

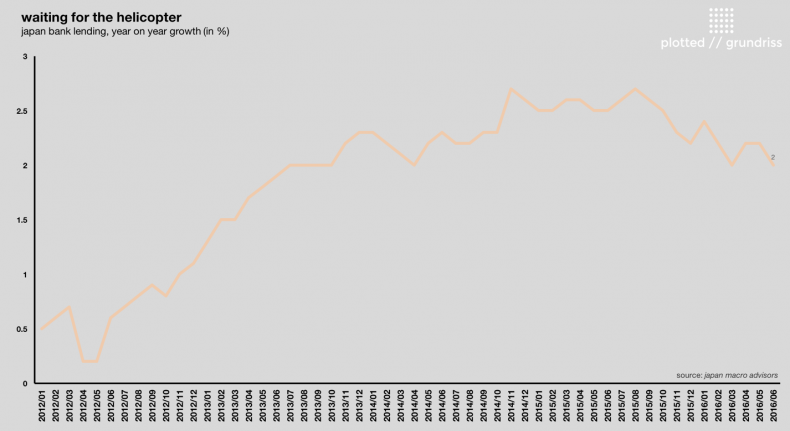

Bringing the BOJ into the stock market and inflating prices was meant to buoy firms into borrowing – and investing – more. This has yet to materialize. For now, the downward trend in bank lending (as well as in investment) continues, despite record liquidity provided by the BOJ and its direct propping up of the stock market (see chart below).

While the hoped for effects thus remain elusive, the negative side effects are more tangible – and will amplify as the BOJ and public investors pile up shares. The government pension fund, for instance, never signed up to the corporate governance codes pushed by the government it is a part of. The GPIF’s investment principles are few and vague, and in Benes’ words amount to “not much.” But while the GPIF is still beholden to some principles and subject to fiduciary obligations – and, in principle, can be sued – none of these options are available against the central bank, he adds.

Since a central bank has no fiduciary obligations, it cannot be legally held accountable for its investment decisions. And unlike pension funds, which make long-term investment decisions, the BOJ is an unpredictable investor: it is unclear when the BOJ will scale up or wind down its ETF program, or how fast. The political climate, for instance, may move against stockholding by the BOJ as sudden as Abe pushed it toward activism in 2012. At the same time, this ETF-based de-privatization is undermining the government’s push for more activist shareholding by shrinking the potential for positive selection based on individual company performance, diluting Abe’s corporate governance reforms.

Inc. Japan?

The BOJ’s decision on July 29 to up the ante just makes the questions about the effects of these developments more pressing. Starting out its program of monetary easing in 2012, the BOJ also meant to strengthen Japan Inc. Instead, we might end up with Inc. Japan instead.

Markus Winter is editor-in-chief of the not-for-profit Japan politics and economics blog plotted//grundriss. He also is a lecturer at Hosei University.