Sixty-three years ago, the signing of an armistice agreement stopped the Korean War, which had plunged the peninsula into turmoil and bloodshed three years earlier. On June 25, 1950, the North Korean People’s Army had crossed the dividing line established between the two Koreas by the United States and the Soviet Union in the aftermath of World War II. With the invasion of the South, the Korean War–the first and perhaps most dangerous armed conflict of the Cold War–began.

The war’s human toll was staggering, with millions of civilian casualties and hundreds of thousands of combatants’ lives lost on all sides. The war, which ended in an armistice rather than a peace treaty, had no formal end. It was quickly forgotten by many.

Not surprisingly, the remarkable life story of the man who signed the armistice for the North Koreans is similarly obscured. The records of General Nam Il can be traced from the Russian Far East to Uzbekistan to North Korea, and finally into the history books as footnote from the Forgotten War.

With her brother on her back, a war-weary Korean girl tiredly trudges by a stalled tank, at Haengju, Korea. June 9, 1951. Maj. R.V. Spencer, UAF. (Navy)

The negotiations that preceded the signing of the armistice were the most complex and difficult peace talks in the entire Cold War. They began on July 10, 1951 in the North-controlled city of Kaesong and in several months moved to Panmunjom – a de facto border area between the North and the South.

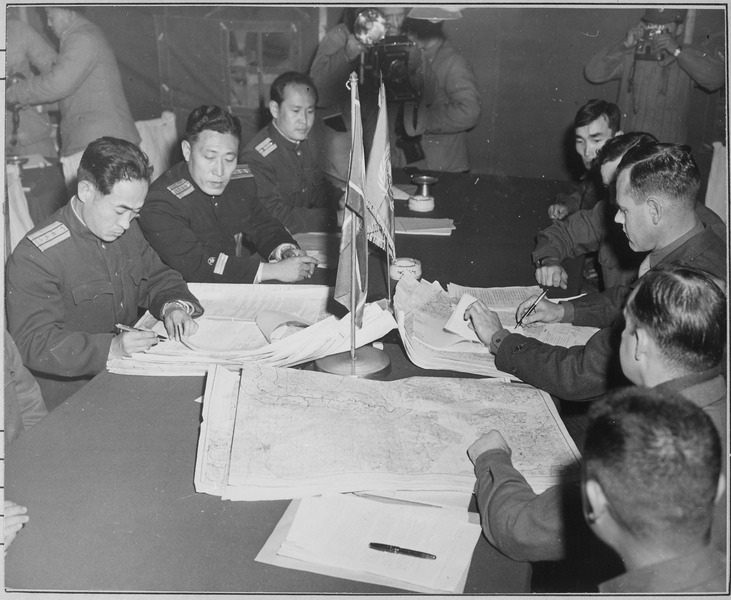

While bloody fighting continued mostly along the 38th parallel, the UN Command representatives on one side – led first by U.S. Admiral Charles Turner Joy and later by U.S. General William Kelly Harrison – negotiated furiously with the Korean People’s Army and Chinese People’s Volunteer Army delegates headed by North Korean General Nam Il.

Colonel James Murray, Jr., USMC, and Colonel Chang Chun San, of the North Korean Communist Army, initial maps showing the north and south boundaries of the demarcation zone, during the Panmunjom cease fire talks. General Nam Il is the middle man on the North Korean side. (Navy)

The pace of talks was tortuously slow. While the exhausted soldiers kept dying in trenches – caught in mortar and artillery cross-fire in scenes reminiscent of WWI – the diplomatic counterparts kept arguing and eventually got stuck in a months-long stalemate over the exact location of the demarcation line and demilitarized buffer zone and the arrangement of technicalities for war prisoners exchanges.

U.S. troops dig in against the communist-led North Korean invaders, somewhere in Korea. (Department of Defense)

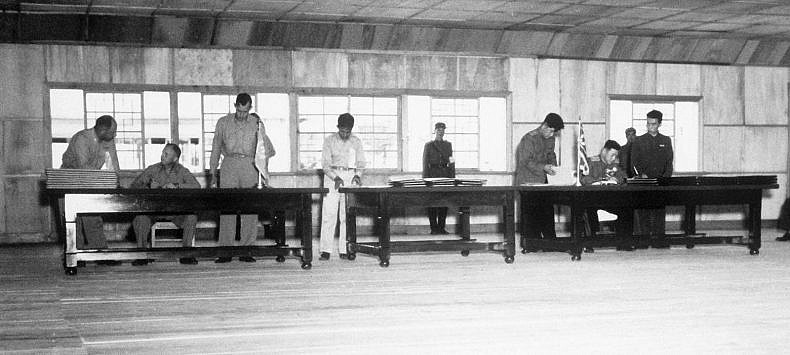

Their discussions dragged on for two years, with over 150 plenary sessions and 500 meetings held at different levels. So when the armistice was finally signed in Panmunjom on July 27, 1953 and effectively ended the fighting, the news very quickly made global headlines.

The photograph of U.S. General William Kelly Harrison and North Korean General Nam Il signing the Korean armistice instantly became iconic. Shortly after, photos of the North Korean delegation at the “peace pagoda” in Panmunjom, where the agreement had been signed, appeared on the pages of most international magazines.

UN delegate Lt. Gen. William K. Harrison, Jr. (seated left), and Korean People’s Army and Chinese People’s Volunteers delegate Gen. Nam Il (seated right) signing the Korean War armistice agreement at Panmunjom, Korea, July 27, 1953. (Department of Defense)

General Nam Il momentarily became the face of North Korea around the world. Even nowadays, his mysterious personality and actual role in the ending of that vicious war is deeply under-discussed, with very few detailed facts known about Nam Il’s rise to power in the military of the world’s most secretive regime.

“He spoke forcefully in Korean, seeming to spit out his words. … At no time did he ever exhibit the least tendency of humor. If he laughed, it was in a sarcastic vein. His smooth … face rarely revealed emotion, and if so the emotion was anger or feigned astonishment.”

General Nam Il sitting in a Russian-made jeep, waiting to depart from the Korean War Armistice Negotiations site at Kaesong, Korea. (U.S. Information Agency)

American military chronicles of the Korean War described General Nam Il as an alleged North Korean of Asiatic Russian origin who had previously studied in Soviet military schools and fought in the Red Army in the rank of tank soldier and later captain in WWII. Both U.S. and Chinese online encyclopedias mention Nam Il’s participation in the liberation of Kharkov, Warsaw, Berlin, and the historical battles of Kursk and Stalingrad.

On the other hand, even Admiral Joy himself speculated in his memoirs published in the aftermath of the armistice negotiations that Kim Il-sung had chosen his chief of army staff as a puppet to formally head the North Korean and Chinese delegation while the man who wielded real power behind the talks was the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army’s General Hsieh Fang.

The irony of Nam Il’s dubious central role in the negotiations of peace on the Korean peninsula extends to the signing of the armistice itself. According to a declassified telegram draft by the USSR Communist Party’s Central Committee, Soviet leaders were extremely worried about possible provocations during the signing ceremony and thus advised Kim Il-sung not to personally participate. As a result, General Nam Il was chosen as the final signatory of the agreement, probably in the same way he had been earlier assigned to lead the North Korean and Chinese delegation.

In order to resolve the mystery of this man who helped settle the modern status quo on the Korean peninsula, we should start at the very beginning: with Nam Il’s family, education, and path into the ranks of power in North Korea.

The Uzbek Connection

At first glance, Uzbekistan – a double land-locked country positioned in the very heart of Central Asia – has no direct relationship with the Korean peninsula. However, this region contains a very painful and dramatic history of forced Korean migration that marks the 20th century almost as brutally as the Korean War itself.

Yakov Petrovich Nam was born on June 5, 1913 to a peasant family in Ussuri Krai in the Russian Far East. Ethnic Koreans, mostly from the north of the Korean peninsula, started immigrating into Russian lands in the early 1860s, and by the late 1930s the number of ethnic Korean inhabitants in the Soviet Far East reached almost 172,000.

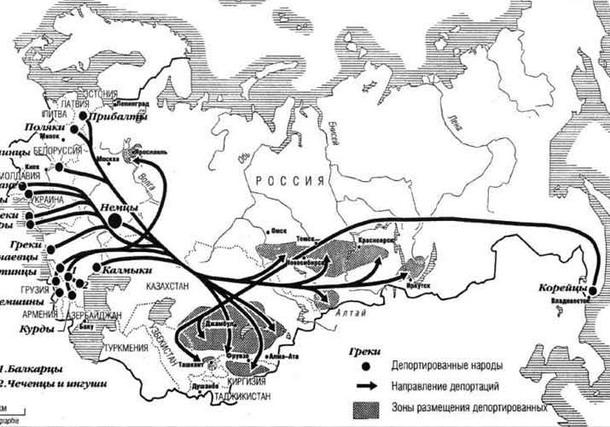

A map showing the forced relocation of “unwanted” ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union throughout the late 1930s – early 1940s. Koreans were the first entire nationality to get deported in 1937 from the Soviet Far East to Central Asia. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

In 1937 all of them, including Yakov Nam’s family, were deported to Uzbekistan in what became the USSR’s first massive transfer of an entire nationality. Suspected of pro-Japanese espionage – for the Korean peninsula at that time was under the control of Imperial Japan – and condemned as enemies of the state, all ethnic Koreans were forcibly put on cattle trains and shipped across Siberia to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in a few short months following Stalin’s orders.

Uzbek Koreans in the late 1940s. Courtesy of Victoria Kim.

It is still unclear if Yakov Nam himself was deported, although very few Koreans escaped the deportation. While American and Chinese sources state that he graduated from a university in Tashkent in 1939, according to declassified information from the Russian state archives, he actually finished his studies in Tomsk that same year.

All sources agree that he chose education as his career field and eventually rejoined his deported family members in Uzbekistan, working first as a teacher and later as a dean and public official. He married to a local Korean woman and had a daughter, and his own family kept living in Uzbekistan together with him.

According to declassified Soviet sources, he worked as a civil servant in Uzbekistan throughout WWII, which effectively discredits the information about his military service in the Red Army and alleged participation in numerous historical battles that’s been ascribed in various encyclopedias.

Between 1941 and 1943, Yakov Nam taught in a secondary school in a small town in the south of Uzbekistan. In 1943, he joined the department of public education in Qashqadaryo region as a deputy head and later head, and stayed there until 1946. For his efforts on the Uzbek labor front during the war, Yakov Nam was even awarded a state medal.

In October 1946, the Soviet Union’s Politburo decided to send the first group of civilian personnel to North Korea. This decision followed a request from the DPRK’s Provisional People’s Committee to provide Soviet professionals in order to train local cadres in the newly established country, which still lacked human resources in the aftermath of WWII and nearly 40 years of Japanese occupation.

Earlier, in May 1946, the Central Committees in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan were asked to identify, select, and train 200 ethnic Korean Communist Party members and members-to-be – 100 people from each of the two republics where all Soviet Koreans had been deported to in 1937 – in order to send them to North Korea.

Kim Il-sung and Kim Tu-bong at the joint meeting of the New People’s Party and the Workers’ Party of Korea in Pyongyang, 1946. Public Domain.

Yakov Nam became one of those first 37 Soviet civil experts in the DPRK. His further promotion in the North Korean Communist Party line was indeed very quick – from translator at the Department of Soviet Civil Administration to deputy director of the education department at North Korea’s Provisional People’s Committee and then to deputy minister of education by 1948.

Holding these key positions in the education sphere, Nam Il helped shape educational policies in the DPRK in line with the USSR’s political directives and successfully converted the Ministry of Education into a key propaganda agency for the North Korean state.

In 1950, he became a member of the North Korean Communist Party’s Central Committee and moved to the National Ministry of Defense, where he kept developing and applying state propaganda and was assigned to a top planning position.

Without any formal military credentials other than his student military practice – as noted in the 1952 declassified internal report of the Soviet embassy in Pyongyang, which even recommended sending Nam Il back to the USSR for an additional military training – he nonetheless became a general and was shortly appointed as the North Korean People’s Army Chief of Staff.

Between 1951 and 1953, General Nam Il was the head of the North Korean and Chinese delegation in the Korean armistice talks and played a crucial role in negotiating and signing the agreement that finally stopped the fighting on the Korean peninsula.

It was he who aggressively insisted during the armistice negotiations on the creation of a military demarcation line along the 38th parallel and the inclusion of demilitarized buffer zone as basic conditions for the end of open hostilities between the two Koreas.

Shortly after the Korean War, General Nam Il was appointed North Korea’s minister of foreign affairs and was re-appointed again in 1957, when he also became vice premier. He effectively kept the title of vice premier for the rest of his life.

Nam Il always kept close to Kim Il-sung. From his personal translator to one of the key people in the DPRK’s government in its most difficult years, General Nam Il consistently demonstrated unconditional loyalty to the North Korean leader.

Eventually, it helped him maintain his position at power while the rest of his Soviet Korean compatriots were methodically purged by the North Korean state in the years after the armistice.

Jacob A. Malik, Soviet representative on the U.N. Security Council, raises his hand to cast the only dissenting vote to the resolution calling on the Chinese Communists to withdraw troops from Korea. Lake Success, NY. December 1950. INP. (U.S. Information Agency)

The purges of Soviet Koreans – those who originally came from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan at the request of Kim Il-sung – began in North Korea after the deterioration of the state’s relationship with the Soviet Union. Stalin had died in March 1953, a few months before the Korean armistice was signed, and Nikita Khrushchev took the helm in September. Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin and dismantling of his personality cult during the 20th Communist Party Congress in Moscow in 1956 fed into the parting of ways among the world’s communists.

Whereas many of his colleagues were gradually stripped of their titles, killed, or deported together with their families to remote areas in North Korea, General Nam Il remained. A Soviet citizen until 1956, he bet on Kim Il-sung over Nikita Khrushchev in the most crucial and critical moment and apparently was rewarded at the time for his choice.

North Korean Premier Kim Il-sung prepares to sign the armistice handed to him July 27, 1953, by General Nam Il, head of the communist delegation at Panmunjom. (Eastphoto)

However, it’s speculated that Kim Il-sung manipulated General Nam Il to publicly criticize the USSR’s new policies during the Soviet leaders’ visit to North Korea in September 1956. Nam Il served as Kim Il-sung’s personal translator during the visit. He even tried persuading the Soviet delegation in his new leader’s righteousness, calling upon them to recognize the wrongs of their own new path.

Even so, he could not indefinitely escape persecution in the vicious and isolated North Korean regime, which systematically eliminated all its opponents, real and imagined. In 1960, his minister of foreign affairs title was revoked, and General Nam Il’s career forcibly shifted in a new direction.

He was appointed chairman of the State Construction Committee and became the new minister of railways in 1966. Between 1962 and 1965, he was increasingly isolated politically. His membership in the presidium (Politburo) of the North Korean Communist Party’s Central Committee was terminated in 1970.

His family in North Korea (he’d taken a new Soviet Korean wife and they had a son) were spied upon throughout the early 1960s – according to rumors from the Soviet Embassy in Pyongyang – while Nam Il himself was also suspected of passing secret information to the Soviets.

In 1972, he became the State Administrative Council’s vice premier and State Light Industry Council’s committee chairman. These were his last two appointments. In early March 1976, Nam Il died in an alleged car accident during one of his inspection trips. He was 62 years old.

Kim Il-sung organized a lavish state funeral for Nam Il, a faithful “revolutionary soldier.” The announcement of his untimely demise came on March 7, 1976 and the funeral ceremony was held on March 9, with state fireworks and Kim Il-sung himself laying the flowers and speaking at the tomb of his fallen comrade.

Even in death, General Nam Il kept his mystery. Now – 40 years later and 70 years since the Soviet Union took the decision to command its first civilian experts to North Korea – it is very difficult to say with certainty if he indeed had become only a puppet in Kim Il-sung’s merciless power struggle or was rather a real hero of the North Korean revolution.

One fact is simply undeniable – this modest Uzbekistani Korean teacher went a very long way and became one of the key military and diplomatic figures in negotiating and signing the armistice that brought a delicate peace to the Korean peninsula on July 27, 1953.

Victoria Kim is a multimedia journalist and researcher from Uzbekistan. She recently wrote about the Soviet deportation of Koreans to Uzbekistan (available in parts one, two, three) in memory of her grandfather, Kim Da Gir (1930-2007), who was among the deported.