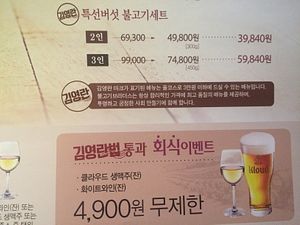

The Anti-Corruption and Bribery Prohibition Act, also known as “Anti-draft Act” and “Kim Young-ran Act” — named after Kim Young-ran, chief of the anti-corruption and civil rights commission, who first proposed a limit on the value of meals, gifts, and congratulatory and condolence money for public officials in August 2012 — took effect on September 28, 2016. The act is aimed at officers and employees of public service organizations, including universities and schools, as well as at journalists. The main provisions of the act are a limit on the price of meals (₩ 30,000/$27), gifts (₩ 50,000/$44), and congratulatory cash gifts (₩ 100,000/$90) officials can receive at events that are not open to the public.

Background

Korean society consists of many interwoven traditions, and gift giving is an important part of this culture in virtually all aspects of societal and business life. After many incidents of public criticism against Korea’s corrupt business culture prior to 2014, the Sewol ferry tragedy was one major catalyst for the Korean public to hold officials and regulators accountable for being all too willing to overlook shortcomings of the ship’s owners.

As a response, on March 26, 2015, President Park Geun-hye promulgated the Anti Corruption Law (Act No. 13278) which won bi-partisan approval in the National Assembly.

The Anti Corruption Law is targeted at public officials, i.e. all officers and employees of public service organizations under the Public Service Ethic Act including state owned enterprises, government institutions and other public institutions as well as teachers, journalists and reporters. Altogether the law affects the officials of 40,919 organizations nationwide, 96.8 percent of which are schools and media companies. In total, about 9 percent of the Korean workforce falls under the provisions of the new anti-graft law.

Since August 28, when the law went into effect, every civil servant who is subject it cannot receive meals worth more than ₩30,000, gifts over ₩50,000, and congratulatory cash gifts above ₩ 100,000 at private events, including wedding ceremonies and funerals. The rules exclude open events such as official press conferences. A violation of the law can lead to imprisonment of up to three years and a fine as high as ₩ 30 million (about $24,000). The act also applies to spouses of public officials.

The Diplomats’ Dilemma

As with any new law, there are many initial uncertainties with regards to its scope and implementation. This is especially true for men and women of the diplomatic community. While diplomats possess immunity from criminal jurisdiction based on the provisions of the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations and Operational Protocols Article 31, they are equally expected to respect the laws and regulations of the receiving state, according to Article 41 of the same document.

Embassies often hold events to which politicians, academics, and journalists are invited, all of which fall under the provisions of the new anti-graft law. Even if the law can’t be enforced against diplomatic entities, an embassy naturally doesn’t want to get its Korean interlocutors into trouble by extending an invitation that violates the provisions of the law.

There are some specific areas and cases that leave the diplomatic community in suspense as to what is legal and what is not; for instance, the invitation of Korean journalists to countries to cover certain events or prior to a head of state’s visit to Korea, where flight tickets, hotels and meals (covered by the respective embassies) will naturally exceed the provisions of the law. Another source of possible embarrassment can originate from the necessity of transparency. Often, ambassadors invite distinguished guests to their private residencies and entertain fancy dinner parties, and many of the invitees are members of the political and academic sphere. It remains unclear how the host is supposed to provide transparency on the expenditures for such an event, keeping in mind that the venue is an ambassador’s home.

Further uncertainties include many embassies’ practice of awarding scholarships to government officials to continue studies at universities in their home countries, as well as the sponsoring of commercial and trade related events.

While the foreign business community, which is less familiar with and connected to the Korean traditional gift-giving and guest hosting culture, generally welcomes the new law, it can be expected that there will be plenty of occasions in the future where not only Koreans, but also foreigners, especially foreign officials, will come into conflict with the new Kim Young-ran law.

Maximilian Ernst is Managing Editor at the Global Politics Review, Journal of International Studies. He is a graduate of Yonsei University Graduate School of International Studies, where he majored in International Security and Foreign Policy, and the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, where he majored in Chinese Studies.