The Chinese footprint in Europe has expanded significantly over the last decade. In 2015, Chinese investment in the European Union (EU) reached a record high of USD 23 billion, from less than USD 3 billion in 2009. In this context, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) also receives an unprecedented level of attention. To further economic cooperation with the region, the fifth “16+1” Summit between China and 16 CEE countries concluded on November 5, in Riga, Latvia where Chinese authorities played a key role in closing new deals.

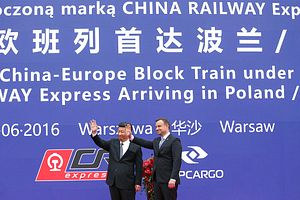

China-CEE cooperation is an initiative similar to other Chinese market penetration strategies, but also one of the main platforms aimed at enhancing multilateral cooperation within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This initiative, a modern Silk Road, promotes the economic integration of China, Asia, and Europe by improving infrastructure and increasing trade and investment.

Within this broader initiative, Europe is emerging as one of the top destinations for Chinese capital. And the countries of CEE represent a very different market proposition, and a potential platform for China to leverage its growing economic and political influence with the EU as a whole.

China’s “go global” approach

As the Chinese economy matures, Outbound Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI) is becoming one of its main drivers to promote economic growth. The first Chinese “go global” phase in the early 2000s aimed at exploring viable market opportunities, trade relations and access to natural resources. Most of the investments were channeled to Asia, Africa and Latin America. China’s main objective is to move up in the high technology ladder, meaning the current phase of investment is focused on advanced technologies, knowledge industries, transportation and distribution networks and global market influence. According to UNCTAD data, Chinese global OFDI has been on an impressive growth trajectory for the last decade, hitting around $130 billion in 2015, turning China into a key investor representing approximately 10 percent of the global ODFI outflows.

China and the EU

In the eyes of Chinese investors, Europe is portioned into two distinct zones consisting of the West and the East, based on variances in economic wealth and technological advancement. This drives a diversified strategy of Chinese investments in Europe.

Chinese FDI in Western Europe, mainly in the United Kingdom, Italy, France, Portugal and the Netherlands is aimed at engaging with Europe’s strategic assets and research and development networks. Merger and acquisition (M&A) activities and joint ventures have been the main market entry mechanism to date. Key target sectors include real estate and hospitality, automotive, financial and business services and information technology. In particular, Chinese companies are interested in acquiring companies with strategic assets giving them access to established brands, technology and distribution channels.

Additional overseas opportunities for Chinese companies in the EU have been created by the economic crisis in Europe and the need for capital, the privatization process and post-crisis restructuring. Government-backed Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) remain the dominant players, supported by financial assistance from state-run and commercial banks and sovereign funds. Interestingly, sectors such as finance, telecoms, logistics and public procurement are restricted to foreign investors in China but open to Chinese investors in the EU. This amplifies the political aspect of asymmetrical market access and lack of reciprocity. In fact, European FDI in China is stagnating or even declining.

Chinese interests in CEE

The 16 CEE countries present a very heterogeneous group, including 11 EU countries and five EU candidate countries in the Balkans. The differences across the region are significant in many aspects, including the level of economic development, per capita income and institutional framework. Despite this, China has clustered the CEE as one region that maps to its main objectives: transportation networks for the Silk Road, and investment goals for further capital expansion across the EU.

There appear to be four principal reasons for China’s growing interest in CEE:

First, China is mainly attracted to the region for its strategic position and ability to reduce transportation costs for delivering Chinese goods to Western Europe. One of the main outcomes of the Riga conference was a deal on the construction of the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway. This major infrastructure project, expected to reduce significantly the transport time of Chinese products into Europe, will be funded by the Exim Bank (USD 2.5 billion) and implemented by China Railway and Construction Corporation.

Second, the CEE represents a collective population of over 120 million with rising per capita income levels, offering new market opportunities, thus heightening the region’s appeal to Chinese market-seeking FDI.

Third, Chinese investment interests within the CEE region appear to be very strongly related to ongoing privatization opportunities, including large scale infrastructure projects and public procurement opportunities.

Fourth, Chinese investment is expanding towards more efficiency-seeking FDI influenced by human capital assets in the region, and relatively low labor costs. As labor costs rise in China, manufacturers may find it cheaper to locate production facilities closer to their EU destination markets.

While Chinese investment in CEE remains at modest levels (only in Hungary the aggregate Chinese FDI is above 1 percent of GDP), it is growing rapidly. The most advanced and largest countries in the region have received the largest share investment over the last 15 years: Hungary (USD 2 billion), Romania (USD 741 million), Poland (USD 462 million) and Bulgaria (USD 222 million).

In turn, attracting Chinese investment to the region remains a key goal of the CEE countries. Eastern Europe economies account for 8 percent of total Chinese investment in Europe. CEE leaders have been courting Chinese direct investment in the hopes of stimulating job creation and infrastructure growth. In 2013, China promised, and reiterated again in Riga, to create an USD 11 billion “China-CEE Fund” to finance projects in CEE. Despite this pledge, Chinese investment comes with many strings attached. Projects have to be highly viable economically, require Chinese companies to be the main contractors and Chinese labor to implement the projects.

Looking Ahead

Arguably, there also exists a political opportunity behind China’s interest in the CEE region. By building up assets in CEE and fostering competition among the target countries, China is first increasing its economic and political influence in the region, and thus, enhancing its bargaining power with the EU, especially in light of the much-expected Bilateral Investment Agreement (BIA) between the EU and China, first rolled out in 2012 and currently under negotiation. In order to successfully negotiate the BIA, the EU needs to speak with one voice. Arguably, this may become more difficult as it appears that the relationship between China and the EU continues to be primarily driven by individual member state interests to the detriment of wider EU objectives.

The “16+1” initiative will create more opportunities for China to direct its products, capital, labor and services to the CEE. However, Chinese spillover in this region will not remain confined to infrastructure, trade and investment, but may also slowly extend into politics, culture and security (e.g. in Serbia). Consequently, it is increasingly important for European policymakers to pay closer attention to China’s investment strategies in the CEE countries. In order to maximize China’s engagement in Europe, while simultaneously hedging against its risks, perhaps it is time to initiate a new debate about how to best coordinate a comprehensive response at the EU level taking into account both the benefits and consequences of Chinese investment in region.

Valbona Zeneli is a professor of national security studies at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. The views presented are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the views of the George C. Marshall Center, German Ministry of Defense or the U.S. Department of Defense.