After the partition of the Indian subcontinent, Pakistan’s relations with Afghanistan didn’t get off to a good start. Afghanistan refused to accept the British-imposed Durand line as a legitimate border and cast the sole vote against Pakistan’s membership in the United Nations in addition to laying claim to Pakistan’s Pashtun tribal areas. During the 1950s and 1960s, Afghanistan sponsored a Pashtun separatist movement in Pakistan’s tribal areas. Pakistan has always considered Afghanistan’s support for a Pashtunistan a threat to its national security.

During and after the Cold War, Pakistan supported certain sections of ethnic groups in Afghanistan. During the Taliban era, while refuting this publicly, Pakistan sided with the Taliban. After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, a majority of militant groups that Islamabad had supported across the Durand line took refuge in Pakistan’s Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA). The presence of these groups, which at one point was approved and encouraged by the state, further encouraged radicalization in the area.

The uprisings in the FATA since then have not been purely Islamist. Pakistan has tried to unite its tribal regions away from ethnic considerations and toward Islam. Throughout history, Pakistan’s foreign policy toward Afghanistan has been defined by a mix of realpolitik and Islam. Arguably, the recent uprisings were influenced by both ethnonationalism and religious considerations.

For instance, Pakistan was one of the few countries that endorsed and celebrated the Afghan Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in 1996. However, the ideological outlook of the Afghan Taliban that was promoted by Islamabad proved ineffective as the Taliban refused to settle the Durand line border dispute with Pakistan and further promoted ethnic Pashtun nationalism in the region. Thus, while uprisings in the FATA had an Islamic character, ethnonationalist impulses have always remained an essential part of all jihadist movements in the region.

Today, Pakistani military operations in the FATA region have produced some concrete results. However, these operations have been selective: The military still continues to believe that some militant groups should not be targeted. The policy of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ militants remains in place. The focus has been on pushing out groups that have targeted the Pakistani state such as the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan. Pakistan has not targeted groups that target Indian or Afghan interests and are based in Pakistan. The Taliban’s Quetta Shura leadershi[p and the Haqqani Network still continue to operate from inside Pakistan. On Pakistan’s part, the policy of selective counterterrorism does not serve the country’s interests in the long run. Kabul, for example, is now likely to use a “tit for tat” strategy against Islamabad by providing sanctuaries to groups that target Pakistan’s interests.

Moreover, Pakistan’s militant challenges are just beginning. The real challenge comes from sectarian groups that have gradually expanded to tribal areas with massive support in Pakistan’s mainland. The recent attacks in Balochistan provide a troubling example of a growing nexus between different militant networks with presences across the state.

Recent military operations in Pakistan’s tribal areas have been carried out in secrecy, as well. Besides the official press releases that by and large contain numbers of killed suspects, no other information has been made public. A majority of the media trips that have taken place in the tribal areas in recent years have been arranged by the Pakistani military. The objective behind this secrecy is to control the flow of information regarding the operations being carried out in the region. Such an approach will not help in bringing peace and stability to the region.

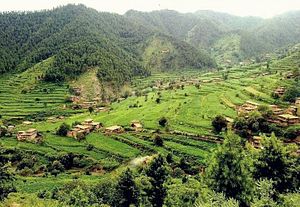

Pakistan needs a long-term plan to rid its tribal areas of the military. The reconstruction and rehabilitation of the FATA region should not take place in secrecy through a micromanaged process. Rather, this process should be inclusive, public, and led by the country’s political leadership. The local sociopolitical dynamics of the area should be restored to what they were before the jihadist takeover. Moreover, the economy of the FATA region should be brought to the level of other developed regions, for better economic incentives can prove effective in containing the growth of militancy, which, among other drivers, thrives on the region’s dire socioeconomic realities.

Above all, the first step in this regard should begin with the state giving up its policy of allowing militants to travel, stay, and interact with local communities in the FATA. If not, attacks and violence will only continue.