The fate of the People’s Republic of China as a political project is increasingly dependent on one man – Xi Jinping. Already known informally as “the chairman of everything,” the sixth plenum of the 18th Party Congress recently declared him the “core” of the Communist Party of China (CPC) leadership. Rumors abound that he now intends to violate the party’s own norms of leadership selection at next year’s Party Congress by changing the retirement age in the Politburo Standing Committee and neglecting to name a successor.

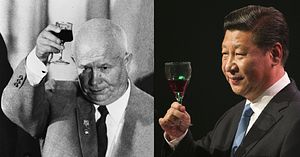

Recognizing the extent of Xi’s ambitions, scholars have attempted to better understand his prospects by comparing and contrasting him with a whole swathe of other leaders, including Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Chiang Kai-shek, Vladimir Putin, and even the pope. However, in terms of his ambitions, strengths, and weaknesses, Xi most obviously resembles the former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.

Both Khrushchev and Xi came to power believing only major reforms could save the revolution. Xi enjoys the same sources of resilience Khrushchev possessed – a widespread sense that change was needed, a tradition in the party of obeying the top leader, a common understanding that factional infighting would damage the party’s unity, and the difficulty for conspirators to organize a coup.

However, neither leader attained the prestige of their predecessors, whose victories brought the communists to power. Also like Khrushchev, Xi cannot claim the unambiguous authority a fully institutionalized leadership selection process might have provided. History shows that these limitations meant Khrushchev’s options for out-maneuvering opponents were constrained in important ways.

Looking back on the Khrushchev era, Xi might see good news and bad news. How he manages those dilemmas are up to him. For outside observers, lessons from Khrushchev’s reign will help us determine whether he is succeeding.

Two Ambitious Men

Khrushchev believed that without serious alterations the regime faced a bleak future. We now know that Stalin’s successors were united in their belief that the Soviet people would not tolerate terrible living conditions forever. As Khrushchev put it, “Only our long-suffering Russian people would put up with [poor living conditions], but we can’t go on banking on their patience.”

The Chinese leadership today is also deeply concerned about the future. The era of Hu Jintao is widely seen as a wasted decade during which problems continued to deepen. As Kenneth Lieberthal wrote in 2012 as Xi was coming to power, “painful decisions are essential to avoid snowballing structural drags on growth and heightened social tension and instability.”

Motivated by a sense of crisis, both leaders initiated ambitious agendas: restructuring and cutting the size of the military; fighting special interests inside the capitol and regionalism in the rest of the country; eliminating corruption; destroying potential competitors within the elite; and improving the country’s position on the world stage. Although Khrushchev is often associated with a “thaw” in politics, by the end of his reign he had turned against liberal intellectuals – a position held by Xi from the beginning of his tenure as leader.

The Strengths of Leninist Leaders

Khrushchev was removed from the leadership in October 1964, but his defeat was far from inevitable. Until his sudden removal Khrushchev was a strong leader, and Xi can use similar political assets to manage potential opponents.

First, Khrushchev could effectively draw upon widespread hopes for a better society. After World War II and the Stalinist era, many among the Soviet leadership and populace hoped that Khrushchev would end decades of deprivation. Even after Khrushchev’s purge, many conspirators praised him in their memoirs for his ambition and boundless energy, which they contrasted with the rather uninspiring Brezhnev.

Second, at least while Khrushchev was in power, his colleagues tended to defer to his will. As Khrushchev’s former nemesis Viacheslav Molotov once wrote in a letter to the Soviet Central Committee, “Where, in all the material after 1957 [when Molotov was removed from the leadership] and all the way up to October 1964, can even the slightest opposition to Khrushchev be found?” In other words, sycophancy, not compromise, was the main feature of elite politics.

Therefore, until his removal, Khrushchev faced few direct constraints from colleagues at the top. In the meantime, he was able to force through deeply unpopular decisions like the separation of many local party committees into industrial and agricultural branches.

Third, Khrushchev’s potential opponents were concerned that factional infighting could get out of hand and threaten the stability of the whole party. According to one memoir account, when the Soviet ideologue Mikhail Suslov was first told of the plot against Khrushchev, his lips turned blue and his mouth twitched: “What are you talking about?! There will be a civil war.”

Fourth, because of obvious collective action problems, conspirators faced a difficult task. Who would dare be the first person to start a plot if failure meant removal from the leadership? When one co-conspirator suggested to Brezhnev that they try to remove Khrushchev without executing a coup, Brezhnev almost screamed, “I already told you: I do not believe in open conspiracies; whoever speaks first will be the first to be hurled out of the leadership.” The plotters were not guaranteed to win – Brezhnev not only wept in fear when he heard Khrushchev might be aware of the plot, but he may have even asked the head of the KGB to take the safer path and simply kill the first secretary.

These advantages mean that even though Khrushchev was ultimately removed from power, his loss was not guaranteed. The plotters were in fact only able to make their move because of a highly contingent event – the untimely death of Khrushchev’sally Frol Kozlov, the second secretary and party head of the KGB, police, military, procuracy, and the courts. As one former party figure later wrote, “My strictly personal opinion is that if Kozlov had lived until the CC plenum in October 1964, Khrushchev’s opponents would have achieved nothing.”

The Weaknesses of Leninist Leaders

Khrushchev did of course suffer from important weaknesses, and Xi must confront these same problems today. Neither leader developed the personal authority of old revolutionaries like Stalin, Mao, or Deng. At the same time, the poorly institutionalized nature of Leninist regimes means that neither could attain what Max Weber called “rational-legal” authority: the legitimacy inferred after winning victory in an unambiguous and universally supported process. Without those two strengths, no leader can be sure that he is untouchable.

Given these disadvantages, can a Leninist leader achieve significant reforms? Especially after the experience of Mikhail Gorbachev, the Chinese share Khrushchev’s belief that the only appropriate tool for reform is a disciplined and unrestricted party. But how can a leader reform an organization that is also his own source of power? Or, in the words of anti-corruption czar Wang Qishan, can a surgeon operate on himself? While we cannot predict the future, the following lessons from the Khrushchev era give us better traction for understanding Xi’s potential vulnerabilities.

First, many techniques employed by Khrushchev to shore up his authority proved weak over the long-term. His habit of purging leaders from the leadership even before they could form a faction led to concerns among others that their position was not secure. Khrushchev’s attempt to promote new, young leaders beholden to him only helped inspire the move against him.

Khrushchev also developed parallel power structures like the party and state control commissions to give him some leverage over the party. However, he refused to give them enough authority to challenge his own leadership. Despite those concerns, ultimately the head of the party control commission participated in the conspiracy.

Second, Khrushchev struggled with the problem of delegation. By being at the center of every decision he was culpable for every failure. The sheer size of the problems meant victories were few, especially given the indirect resistance of local leaders. As Khrushchev complained to Fidel Castro, “You’d think I, as first secretary, could change anything in this country! Like hell I can! No matter what changes I propose and carry out, everything stays the same.” Making matters even worse, when things went wrong Khrushchev upset his colleagues by blaming them instead of accepting responsibility.

However, Khrushchev could not simply share the burden of decision-making. He fired one second secretary of the party, Aleksei Kirichenko, for showing too much independence. Khrushchev then tried to have members of the secretariat serve as second secretary in alphabetical order, but this proved unworkable because the fractured authority led to a lack of decisiveness.

Third, Khrushchev proved unable to keep a reliable hold over the political police and military, known as the “power ministries,” and they played a decisive role in his ultimate defeat. Three crucial figures decided to support the conspiracy only after they were assured the power ministries were on board. KGB head Vladimir Semichasntyi helped ensure Khrushchev’s allies could not rally to support the Soviet leader during the coup. Brezhnev only made the final decision to move against Khrushchev after the defense minister signaled he would not interfere. Kozlov’s control over the “power ministries” was one of the key reasons his death made Khrushchev so vulnerable.

Conclusion

The history of the Soviet Union cannot tell us with absolute certainty what will happen to Xi. As argued above, despite his lack of popularity, Khrushchev’s defeat was not entirely predetermined. However, Khrushchev’s experience does help us formulate questions useful for judging Xi’s strengths and weaknesses as time progresses.

Is Xi seen by other members of the elite as uniquely capable of making necessary reforms? How much unhappiness among special interests do those reforms create? Do we have reason to believe that the level of concern about a coup’s broader impact on political stability may be changing, perhaps because of Xi losing popularity in the party and society? Are members of the elite sufficiently upset or scared that they might risk the danger of being caught in a plot?

To what extent is he seen as violating even ambiguous rules on how leaders are selected? Are personnel changes eliminating opponents or creating new ones? Is the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (a parallel power structure) either too powerful or not powerful enough? How is Xi managing delegation problems? What is the position of individuals in key nodes of power, like in the political police or the military?

Most fundamentally, Xi’s future depends on whether he is able to make real breakthroughs. Just like for Khrushchev, the very act of accumulating power and striving for major victories will put him in a more tenuous position than he would have been otherwise. But without trying, China would face a very Soviet future – stagnation.

Joseph Torigian is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation interested in Chinese, Russian, and North Korean politics and foreign policy. His current research uses archival material to investigate the nature of authority at the elite level in Leninist regimes. He received a BA in Political Science at the University of Michigan and a Ph.D in Political Science at MIT.