Over centuries, many men and women alike have given their lives as the price for bringing disgrace upon their families. Honor killings can be traced back to a variety of civilizations and cultures. In ancient Roman society, men were disgraced by their peers if they failed to punish their female relatives for perceived sexual misconduct and the law held men accountable for the indiscretions of the family. The Bible narrates an incident where the figure of Phinehas drove a spear through an Israeli man and his Midianite wife, outraged by their interracial marriage. Evidence of honor killings is also found in the tradition of the Qing Dynasty in China, where men had the right to kill female relatives whom they alleged had strayed away from conventional morality.

The idea that underlies honor killing is that men are the guardians of morality in a society, and while honor is contained within women, they are incapable of rightly protecting it due to their inferior intellect and might. Hence, men are entrusted with this noble responsibility. Some men also fall as casualties to this crime. The examples given above are evidence that this mindset of male superiority has flourished across social classes, borders, cultures, and centuries. Many societies have advanced away from subjecting women to abuse as a result of their so-called transgressions, yet honor killing is still prevalent today in various areas, including include Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Pakistan

Pakistan suffered a total of 1,636 incidences of honor killing between 2008 and 2010; however, the government has only recently responded to the need to address some of the loopholes in the existing law.

Drawing its lineage from customary practices, previously, if a woman was killed in the name of honor, her heirs or legal guardians could accept diyat, monetary compensation from the culprit in exchange for pardon. Diyat is an optional form of punishment as specified by Sharia, drawing its validity from pre-Islamic Arab traditions, where the culprit can pay a fine to the victim as a penalty. This punishment is also traditionally applied to cases of murder.

In early October, a joint session of both houses unanimously passed a bill amending the Pakistan Penal Code that honor killings fall under. The amended law now places cases of honor killing under tazir, penalty at the discretion of the judge. This means that in every case where there is evidence of honor as a motive, the verdict will be given by the judge, irrespective of the sentiments of the victim’s heirs. The amendment also states that “if the offense has been committed in the name or on the pretext of honor, the punishment shall be imprisonment for life.” This addition gives further clarification on the penalty for this crime. Therefore, the amended law in Pakistan not only straightens out the process by making the culprit directly answerable to the court, it also clearly specifies a punishment so that the implementation and interpretation of the law is simpler.

The issue of honor killing has recently been a source of rich debate in Pakistan, the law having been under immense controversy. Even though, many lawmakers had made attempts at amending the law earlier, the murder of Ms. Qandeel Baloch, a social media icon, by her brother brought this issue to the limelight and unfortunately served as the necessary trigger for this amendment to pass unanimously.

The Global Gender Gap Index ranks Pakistan at 144th out of 145 countries analyzed, which is certainly an alarming statistic. In a country with such extreme circumstances for women, this amendment is a step in the right direction; however, the goals are still far ahead. The law does not provide for the protection of those victims that are harmed or threatened with honor as a motive. Over a thousand honor crimes were reported in 2015 and considering the social stigma against women who report such crimes, a vast majority of cases go unreported. The government and civil society must also ensure that this is not just another elite law; it is vital that the importance of female life and safety trickles down to the grassroots of society. For Pakistan to make any real improvement on this front, it must also legally secure survivors of honor crimes and vanquish the widespread norm of women being physically abused by men on the pretext of disobedience and honor.

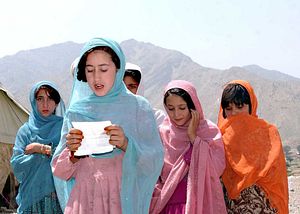

Afghanistan

Afghanistan stands as an appropriate case-study to analyze the aftermath of a women’s safety law in a troubled region. Afghanistan’s Elimination of Violence Against Women Law (EVAW) was passed in 2009. On paper, this law seems holistic and all-encompassing; it criminalizes mental, physical, and emotional abuse, in addition to various other facets of exploitation like “forcing [women] into” drug addition, self-harm, or suicide. Under this law, the common Afghan practice of baad, the offering of a woman in marriage to restore peace between parties, is also prohibited. The law calls for protective and supportive measures, mainly under the Ministry of Women Affairs, by creating awareness about these issues, undertaking research and reporting, and coordinating preventive and security services for survivors of such violence and those under threat. Even the Ministry of Hajj and Pilgrimage is made responsible for creating ground-level awareness and clarifying societal customs falsely portrayed as rooted in religion.

Even amid the existence of civil law and Sharia, customary law has a strong presence among the masses. Civil law and Sharia both condemn violence against women; however, these crimes are legitimized by local customs, many of which were left behind by the oppressive Taliban rule between 1996 and 2001. Between 2011 and 2013, years after the implementation of the law, approximately 400 cases of rape and honor killings have been reported to the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission.

In order for the EVAW law to have any impact, the monopoly of customary law will have to be overcome. The Afghan government has taken the top-down approach in curtailing this challenge, and even though the law plans to change local norms by creating awareness, creating a pro-women culture is a strenuous process, taking even the most developed nations many generations. Until then, the law seems to be a verbose facade that fails to address the real issues.

The Way Forward

The laws of Pakistan and Afghanistan both have respective strengths and a lot to learn from one another. For instance, in Pakistan, the issue of honor killing was directly tackled and now leaves less ambiguity for the interpreter. The penalty is also clearly specified and this makes its implementation simpler. In Afghanistan, the EVAW law deals with violence against women in general, which indirectly involves honor killing cases, but this specific issue has not been addressed head-on. This may leave room for a weaker crackdown on its perpetrators. The Afghan law also does not streamline the jurisdiction of such cases; due to the presence of Sharia, it may still face the same loopholes that Pakistan’s previous legislation faced (namely, the victim’s heirs can choose to accept money or forgive the culprit). This can actually render the law useless given that honor killing is usually committed by the victim’s family, and the majority of cases are unreported.

On the other hand, the Afghan law actually deals with survivors of such crimes and those in danger. This is something that the Pakistani law must move toward so that it does not only deter murder attempts in the name of honor, but all forms of violence.

Honor killing is illegal in both Pakistan and Afghanistan, yet, women in these countries are still suffering due to various toxic societal norms that enjoy considerable respect. Honor killing is the apparent and abhorrent epitome of the physical manifestation of sexism. It incorporates the complete objectification of women: women carry the honor of men instead of an honor of their own which is independent of men. This ideology makes way for the common, degrading analogy that women are like candy: consumed when not covered in dirt, otherwise discarded. Honor killing is one face of this very narrative that dehumanizes women, and extinguishes their individual identity in the absence of a man. Many times this narrative plays out more subtly than in honor killing, however, in order to defeat the symptom, the disease must be cured.

Meha Pumbay is a recent graduate from LUMS with a BSc (Hons) in Economics, and a minor in Political Science. She has been a research consultant with the European Union, USAID, British Council, Senate of Pakistan, Pakistan-China Institute, Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy and Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.