The Uri attack of September 2016 has set the tone for recent Pakistan-India relations. Soon after the incident, which claimed the lives of 18 soldiers, the Indian leadership accused Pakistan of state involvement in the attack, based on evidence including Pakistan-manufactured weaponry found at the scene. However, India’s National Investigation Agency stated shortly after the Uri attack that no solid proof had been discovered to link Pakistan’s involvement.

The Uri terrorist attack is one incident among many in the ongoing deadly turmoil over Kashmir and has resulted in further deepening the historic resentment between the two states. Many longstanding diplomatic institutions have fallen prey to this strained relationship, with the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the Heart of Asia – Istanbul Process as recent examples.

SAARC

The 19th SAARC conference, scheduled to be held in mid-November, suffered the initial brunt of the Indian reaction. Since 1985, SAARC has aimed to bring together the states of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Maldives, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka on economic and cultural grounds.

In order to grasp the significance of this platform, it is important to realise the lack of economic connectivity between these nations, despite their geographic proximity. Even though many of the member states share borders, their trade links are modest. India, being the largest economy of the region, is naturally the most common trade partner for the member states. Pakistan is the second largest economy, and also plays a decision-making role in SAARC.

After the Uri attack, India refused to attend the 19th SAARC Summit to be held in Islamabad, on the grounds of Pakistan’s alleged involvement in cross-border terrorism. Following India’s lead, Afghanistan, Bhutan, and Bangladesh also declined to participate, and the conference was cancelled. This not only pushed SAARC’s aim of regional development further from reality, but also weakened the 2004 South Asian Free Trade Area Agreement.

A contributing factor to SAARC’s meager success to date is that Pakistan and India may not have much to gain from it. India enjoys growing trade with much larger economies and Pakistan has recently attracted massive investment from China. However, if Pakistan and India exhibit more commitment to regional development, the SAARC arrangement could hold high economic benefits, especially for the smaller member economies.

In other words, these stronger economies feed their political agendas at the expense of much weaker neighbours.

Heart of Asia – Istanbul Process

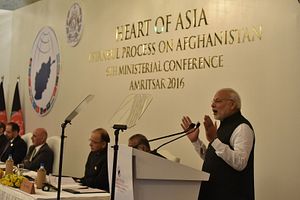

The Heart of Asia – Istanbul Process was established in 2011 to cater to the security, political and economic dimensions of Afghanistan and its surrounding areas. The sixth Ministerial Conference in this series was held at Amritsar, India, on December 3 and 4.

Surprisingly enough, contrary to India’s decision not to participate in the SAARC Summit hosted by Pakistan, Sartaj Aziz, Pakistan’s senior foreign policy adviser, attended the conference in Amritsar, and pledged $500 million in aid to Afghanistan. Due to this seemingly positive step, one may have anticipated a change of direction in multilateral diplomacy where Pakistan and India were concerned. However, once again, Pakistan India problems were at the forefront of the proceedings. The tendency to discuss bilateral matters on a multilateral forum was criticized by the Russian representative, who stated that international fora should not be used for point scoring.

Despite the scolding, Afghanistan and India expressed deep discomfort over the alleged state-sponsored terrorist activities of Pakistan. As a further twist of the knife, Pakistan’s financial aid was declined by Afghanistan, once again citing state-sponsored terrorism as the reason. Even though it had been war-torn for over a decade, Afghanistan declined Islamabad’s monetary aid; it’s easy to imagine that the Transit Trade Agreement with Pakistan seems of little interest to Kabul. This is further proof that Pakistan and India’s mutual agitation results in rigidity at multilateral forums, causing vulnerable economies to suffer and disturbing international diplomatic proceedings.

Interestingly, the U.S. Department of State Country Reports on Terrorism for 2014 and 2015 show a great decrease in terrorist attacks and related casualties in Pakistan and recognize its military accomplishments in “under-governed” areas known to house terrorists. However, cross-border terrorism is a bilateral issue where both the countries have the power to take action either unilaterally, by ensuring stricter patrolling at the borders, or in cooperation, by sharing intelligence and resources to combat mutual threats. Instead of addressing these issues head-on, however, India and Pakistan allow their disputes to spill over into multilateral diplomacy, to the detriment of the region and the world.

Meha Pumbay is a recent graduate with a BSc (Honors) in Economics, and a minor in Political Science. Pumbay has been a research consultant with the European Union, USAID, British Council, Senate of Pakistan, Pakistan-China Institute, Pakistan Center for Philanthropy, and Pakistan Institute of Development Economics