Indonesia’s maritime sector gained a boost when on December 21, Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs Luhut Binsar Panjaitan agreed to cooperate with Japan, establishing the strategic bilateral Indonesia-Japan Maritime Forum (IJMF). The two countries agreed to collaborate in the field of maritime security, maritime economy, maritime infrastructure, as well as maritime education and training, as The Jakarta Post has put it.

Seeking strategic cooperation in the maritime and industrial sectors, Luhut invited Japan to contribute to the development of fish markets in Natuna Besar and the energy sector in East Natuna. Furthermore, he hopes that Japan would be interested in constructing a strategic port in Sabang, as well as urging the Maritime Security Board to work with the Japanese on smuggling issues and cleaning up the ocean.

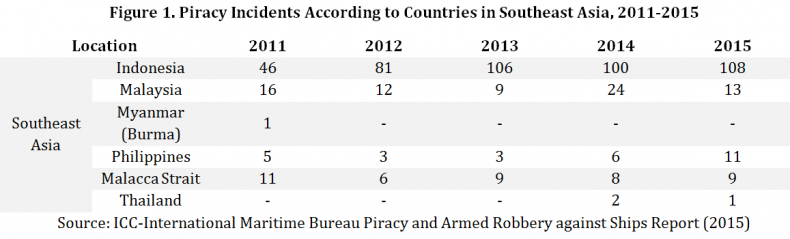

Though the agreement signifies strategic bilateral security cooperation between Indonesia and Japan in term of smuggling prevention, it appears to neglect a growing transnational maritime threat in Southeast Asia: maritime piracy, incidents of which have mostly occurred in Indonesian waters (see Figure 1).

In Southeast Asia, according to a report from a private intelligence agency Dryad, piracy has increased by 22 percent compared to 2014. From 1995 to 2013, Southeast Asia was responsible for 40 percent of the total piracy in the world due to many strategic areas to be opportunistically plundered, particularly in the shipping lanes from the Strait of Malacca to the Singapore Straits and off to the South China Sea.

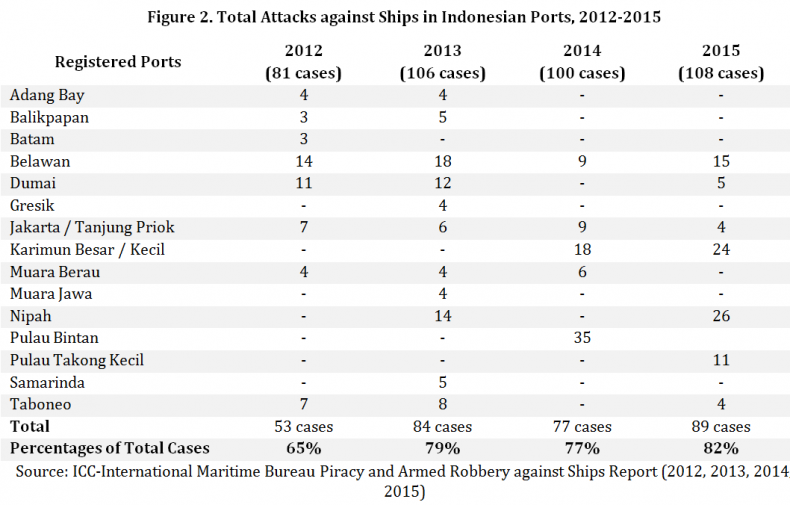

In the case of Indonesia, according to the report from the ICC-IMB that I have compiled in my chapter of a book entitled Reformasi Tata Kelola Keamanan Maritim di Era Presiden Joko Widodo, published by Coordinating Ministry for Maritime Affairs, a substantial number of piracy and armed robbery attacks took place in most major Indonesian ports (see Figure 2).

Another missing concern of Indonesia’s bilateral diplomatic engagement is the lack of success to carry out maritime diplomacy as one of the essential elements of the global maritime fulcrum doctrine. The unwillingness of the head of the Indonesian Maritime Security Board, Vice Admiral Arie Soedewo, to recognize maritime piracy as a plausible threat in Indonesian waters (or even more broadly in Southeast Asia) was reflected in the recent deal with Japan. At this point, it poses a serious question as to the Maritime Security Board’s functional role within Indonesia’s maritime security domain.

Indonesia must strengthen maritime security cooperation through active diplomacy. According to its capacity as a middle-power country, Indonesia should maximize its bargaining position at least in particular fields of interest. Indonesia should actively strengthen maritime security cooperation through bilateral and multilateral channels as a preventative measure, not only reacting when significant threats arise (as, for example, in the case of the establishment of trilateral cooperation with Malaysia and the Philippines after Abu Sayyaf’s kidnappings). Although, as the Japan deal shows, Indonesia is likely to focus more on developing the potential of maritime industries and services without any strategic measures on maritime security, both elements are prominent, and indeed inter-related.

Maritime security, as a vital part of becoming a global maritime fulcrum, should not be neglected for two crucial reasons. First, if piracy and armed attacks against ships cannot be forestalled by Indonesia’s coast guard and navy, it would potentially cause harm to the development of the maritime industry and service sectors. A lack of maritime security along the shipping lanes and ports in Indonesia would be a determinant factor for shipping companies weighing whether to involve Indonesia as a transit point.

Second, vulnerability to piracy may threaten the image of Indonesia as a maritime nation. If Indonesia is able to open up to receiving others’ contributions in the maritime industry sector, Indonesia will also need to respond to and prevent current and future maritime security challenges.

Dedi Dinarto is a researcher at ASEAN Studies Center, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Gadjah Mada and independently concerning on Indonesia’s maritime security issues