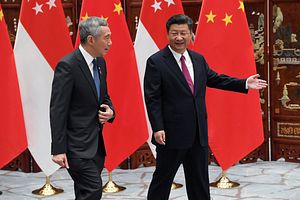

Though it was the Philippines that initiated an arbitration case against China’s South China Sea claims, the most recent and prominent flare-up of Chinese nationalism case was actually triggered by Singapore. This unusual phenomenon can be explained by the ethnic affinity between China and Singapore. With more than three-quarters of its population comprising of ethnic Chinese, Singapore has developed into a Chinese-dominated society. This means that, on one hand, many in China expect Singapore to stand by China or at least keep a neutral stance in sensitive international issues, as in the case of the South China Sea dispute. On the other hand, Singapore has always implemented pragmatic policies in the international arena, thereby usually clashing against China’s expectations. The gap between what Singapore was supposed to do (from China’s perspective) and what it actually does — between the expectation and the reality — disappoints China.

The recent outburst of China’s resentful feeling of ethnic betrayal by Chinese Singaporeans is not a new phenomenon. LKY himself gained a nasty image in China when he called for the United States to reenter Asia so as to balance a rising China in a speech delivered at the U.S.-ASEAN Business Council’s 25th Anniversary Gala Dinner in 2009. The Singaporean leader was mocked in China as “a running dog of the U.S.”

What was the rationale for LKY asking for an increased U.S. presence in Asia, even at the cost of his shiny image as a friend of China? More to the point, do his views on China and Singapore’s role in between China and the U.S. still matter in today’s international environment?

In the Region: “We Are Part of Southeast Asia”

LKY attached the most importance to Singapore’s regional neighbors when he negotiated with various parties, including China. Besides the Singaporean identity as a nation-state, LKY stoutly claimed Singapore’s affiliation with the region: “We are part of Southeast Asia.” Indeed, Singaporeans would rather be deemed Southeast Asians than “Chinese overseas” or “overseas Chinese,” because they believe both of the latter terms reflect a China-centric mentality.

For a long time, two factors above all concerned the Southeast Asian countries when they were coping with China. First were the relations between the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the communists in Southeast Asian countries. During the 1950s-60s, governments of Southeast Asian states found themselves engaged in armed struggles with communist factions. The latter were widely believed to be backed by the CPC and that perception did much to undermine China’s relations with those countries. Second, and closely related, were issues pertaining to Chinese overseas and overseas Chinese. Southeast Asian governments had been suspicious of their Chinese minorities’ loyalty, worrying that they constituted a “Fifth Column of China” that was manipulated by communist China to overturn the Southeast Asian regimes.

Since its independence, Singapore has been facing a “Chinese problem.” Its neighbors — most notably Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines — all were in the throes of an anti-Chinese movement due to concerns over Beijing exporting communism. As a new nation-state that was dominantly populated by Chinese, and in which the domestic left-wing party was rather active, Singapore was viewed suspiciously by its Southeast Asian neighbors and the West. It was misunderstood as a “Third China” or the “Fifth Column of China.”

LKY did not want to see this situation. In order to keep a distance from China, he made sure his first official visit to China in 1976, as well as the ensuing visits, were conducted entirely in English. This gave his worldwide audience the impression that he was Singaporean instead of Chinese and that Singapore was not a Third China. He also, shockingly to many, declined the gift offered by his Chinese host: a book about the Sino-India war of 1962. In addition, Singapore was the last Southeast Asian country to establish a diplomatic relationship with China.

Proclaiming itself a loyal member of the Southeast Asian family has required Singapore to handle China-related issues cautiously. One thing that Singapore needs to take into serious consideration when formulating foreign policies toward China is its Southeast Asian neighbors’ China policies. Nevertheless, this does not mean that LKY was willing to let others determine Singapore’s relations with China, a country he had long ago seen as having tremendous prospects that Singapore could benefit from. On the contrary, LKY proactively mediated among his neighbors, helping Southeast Asia to understand China’s dramatic changes since Deng Xiaoping’s era. Furthermore he also unhesitatingly argued against China-threat theories.

In Between the East and the West: Pragmatic View on Friendship

LKY skillfully navigated Singapore among the world’s great powers. He recognized that in this globalized, interdependent world, the survival of small countries relied on the stability of big ones. With China rapidly rising into a regional great power, the traditional power division between the U.S. and China is losing balance and has, therefore, become Southeast Asia’s biggest concern. As an influential politician in a region full of small countries, among which Singapore is an economic leader, LKY took the lead in negotiating between China and America, in the best interest of his country as well as regional security.

Throughout that process, Singapore and China have understood friendship differently. China fondly imagined that ethnic supremacy grounded an unquestionable Sino-Singapore friendship. However, LKY always examined Singapore’s alliances through the lens of Singapore’s interests. Who is a true friend, the United States or China? He laid his first bet on Washington because the United States had been a gentle hegemon that he knew well for a long time. But what about China as a giant neighbor and a fast rising superpower? Surely it would not be wise to offend this sensitive giant: “When we do something they don’t like, they say you have made 1.3 billion people unhappy.”

Three of LKY’s maneuvering efforts reflected his principles on this balance of power.

First, he tried to persuade other small states to stay on good terms with the big powers. LKY realized that if the big powers were enjoying peace and prosperity, the benefits would flow out to all the small states in the region. He alerted the small countries not to challenge any big power, but also to avoid being manipulated.

Second, LKY appealed to the big powers to give consideration to the security of small states when they were taking any political, economic, or military action in the Southeast Asian region. He raised his voice in China’s competition and dispute with other big powers, the U.S. in particular. During the Taiwan Strait Crisis in 1996, for instance, he reminded Washington that its intervention — such as economic sanctions on mainland China — would bring a negative impact not only to mainland China, but also to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and ASEAN. He added that if the United States rushed into head-on confrontation with China, the entire Asia Pacific region would be in danger and Washington’s own strategic interests in the region would be damaged

Finally, LKY was also dedicated to promoting a mutual understanding between China and the West. Several incidents in 1999, including the NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, the failure to attain a bilateral agreement between China and the U.S. about China’s prospect of joining WTO, and the creation of “two Chinas” theory by Lee Teng-hui, soured the U.S.-China relationship. In order to alleviate the tension between China and the United States, LKY reminded Washington that to antagonize China was not in U.S. interests. At the same time he suggested that China take full advantage of American market, technology, and capital for its domestic development.

Specifically, the above points were reflected in LKY’s view on issues concerning Taiwan and Hong Kong. He pointed out that Taiwan’s unification with or separation from China would be decided not by Taiwan, but by China and the United States. He asserted that the proponents of Taiwan independence would not only endanger Taiwan, but also the entire Southeast Asia. He also stressed that what the U.S. was really concerned about in Taiwan is not the 23 million Taiwanese, but using the democratic Taiwan as an argument against the undemocratic mainland China. Similarly, LKY appreciated the mutual sincerity and respect between China and Britain on solving the Hong Kong issue.

Implications for China: Singapore and the South China Sea Disputes

LKY clearly differentiated his ethnic identity and political identity, and politically he regarded himself as belonging to several communities. He was a leader of Singapore, a prominent politician in Southeast Asia, and his strategic vision was also worldwide recognized. His political worldview was foremost positioned in the geopolitical and strategic situation of Singapore, a tiny city-state neighbored by big powers. He likened Singapore to a small shrimp surrounded by schools of big fish, and to a little mouse standing beside a huge elephant. Under these conditions, surviving in a hostile environment and widening Singapore’s economic and political space became the essential theme for the Singaporean government and its people. This compels Singapore to make as many friends as it can and at the same time maintain an independent course.

During the past several years, the basic principles of Singapore’s efforts in dealing with ASEAN, China and the United States are as follows. First, Singapore acted as a leading member of ASEAN, promoting integration in economics, politics, and security, and making sure ASEAN remains in the driver’s seat of East Asian economic cooperation. Second, Singapore made great efforts to strengthen bilateral relations with China by developing economic cooperation in manufacturing industry and trade. In addition, Singapore welcomed talents from China. Third, Singapore kept a de facto alliance with the United States and supported its presence in Southeast Asia.

Deeper economic and social integration pushes ASEAN countries to form a political community as well. Members are increasingly demanding a unified stance on world affairs. Among the regional security issues, the South China Sea dispute remains the essential concern of ASEAN members. Singapore is not the only Southeast Asian country that has critiqued China in the dispute, but has particularly upset the Chinese. Singapore intends to be a “true friend” of China, but its efforts often subverted the traditional belief in China that “blood is thicker than water” and thus aroused their resentful feelings of ethnic betrayal. Given that even the sophisticated LKY was denigrated as a “running dog,” it is not an exaggeration to say that Singapore’s new generation of leadership is facing great challenges in dealing with China. Constrained by various factors, it is difficult for Singapore to exert an effective role in settling the South China Sea dispute.

China should focus its efforts on fulfilling the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) instead of stressing Singapore’s words and deeds regarding the South China Sea dispute. China should use its South China Sea policy to facilitate the implementation of the BRI in Southeast Asia and harmonize maritime interests among regional states. Southeast Asia is critical for the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road; the Indo-China Peninsula is the joining zone of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road.

Past experiences indicate that the economic cooperation of Southeast Asian countries is not a solution for territorial disputes in the South China Sea. However, the disputes can inversely impact on the extent and depth of economic cooperation as well as on regional politics and security. As discussed, the main cause for China-Singapore tension is the South China Sea issue and the broader U.S. Asia-Pacific strategy the issue reflects. To cool these tensions, it is time to expedite the realization of a code of conduct for the South China Sea.

As the biggest country along the South China Sea and a responsible rising power, China should not only stick to protecting its own interests in the SCS disputes. A win-win outcome should be the right one. Hence, China needs to claim its rights as clearly as possible and take the lead in finding a solution to the disputes that can be collectively accepted by all claimant states. In order to find such a solution, it is imperative for China to cooperate with the claimant states as well as other states that are benefiting from the South China Sea, including Singapore. During the process of dispute settlement, rules and red lines might be included.

Chen Nahui is a PhD student in History at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She researches Sino-Singapore relations with a focus on the Chinese perception of Lee Kuan Yew.

Dr. Xue Li is Director of Department of International Strategy at the Institute of World Economics and Politics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.