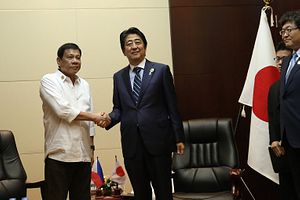

Seeking to turn geopolitical risk and political uncertainty into a strategic opportunity to demonstrate Japan’s role as regional leader, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe kicked off 2017 with a two-day trip to the Philippines. Notably, Abe announced a five-year, one trillion yen ($8.66 billion) aid package, consisting of both public and private sector funding, targeting infrastructure development. That this marks Japan’s largest aid package to a single country, compared to 800 billion yen ($7.7 billion package) to Myanmar, signals the focus of Japan’s strategic competition with China in Southeast Asia has shifted to the Philippines. The two leaders also signed five bilateral agreements, including a $5.2 million grant for high-speed patrol boats for the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) and a Memorandum of Cooperation (MOC) between the PCG and Japanese Coast Guard on maritime security. Abe also pledged cooperation in countering the country’s illegal drug epidemic, a priority for Manila.

Abe’s visit should be seen as follow-up to President Rodrigo Duterte’s trip to Tokyo in October 2016 where Japan offered a $48 million government loan package along with $1.85 billion in private sector Memorandum of Understandings (MOU) and Letters of Intent (LOI) from such companies such as Toyota and Mitsubishi, in addition to a verbal pledge by Marubeni to invest $17.2 billion over the long term. Without specifically mentioning China, the two leaders issued a joint statement recognizing the two maritime nations’ shared interest in maintaining freedom of navigation in the South China Sea and application of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to peacefully resolve maritime territorial disputes.

More to the point, Abe’s outreach to the mercurial Philippine president is driven by Tokyo’s strategy to forge a closer strategic partnership with Manila in order to balance a resurgent and assertive China, which is challenging the regional status quo and destabilizing regional security. Viewed from Tokyo, China’s militarization in the East China and South China Sea directly threatens Japan’s territorial integrity and sea lines of communications (SLOCs), which are vital to its national economic survival. Japan also seeks to defend its political influence with Manila as well as its long-established network of finance and trade ties against Chinese encroachment. These geopolitical and geo-economic drivers are highlighted by the fact that Abe’s trip to the Philippines was part of a six-day tour that included Australia, Indonesia, and Vietnam — all key nodes in Japan’s regional strategy.

Although Japan is the Philippines’ largest trade partner and source of foreign investment, China has begun to make significant inroads. When Duterte visited Beijing in October 2016, he was welcomed with $24 billion in pledges that included $9 billion in loans and Memorandum of Understandings (MOU) worth $13.5 billion. While Japan cannot afford to quantitatively outspend China, it retains a qualitative advantage of being a proven long-term investor that is more likely to implement aid and investment pledges fully. However, in December 2016, Manila opted to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which has less rigorous risk controls than the Japan-led Asian Development Bank (ADB) headquartered in Manila.

Another major strategic concern in Tokyo is the populist Philippine leader’s notoriously confrontational stance toward Washington. Duterte has downgraded defense cooperation, restricted joint military exercises with U.S. forces, solicited China and Russia as alternative weapons suppliers, and raised uncertainties about his commitment to implement the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA). Signed in 2014, the EDCA grants U.S. forces access to five Philippine bases on a rotational basis, thus elevating bilateral defense cooperation to its highest levels since the U.S. withdrew from Clark Air Base in 1991 and Subic Bay Naval Base in 1992.

Although Manila is unlikely to abrogate its 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty with the United States to align with China and Russia, one purpose behind Abe’s visit was to press Duterte for clarification and reassurance about his foreign policy priorities and intentions. It is uncertain whether U.S. President Donald Trump — who has vowed to take a hard line toward China, along with demanding more from U.S. allies — will “hit it off” with his Philippine counterpart and work to rehabilitate bilateral relations. While Trump is not expected to pressure Duterte over his bloody war on drugs, asking the Philippines to increase its “burden sharing” is probably a non-starter. Rather, Duterte may demand that Washington do more for the Philippines while seeking to maintain an omnidirectional state of equilibrium between the major powers. If so, then the bilateral relationship is unlikely to return the level of solidarity under former President Benigno Aquino III.

Duterte’s push for a more “independent” foreign policy — aimed at extracting maximum economic and financial concessions from his geopolitical suitors — presents both opportunities and risks for Japan. On the downside, a potential surge of Chinese capital and trade expansion could disrupt Japan’s longstanding trade and investment networks and displace Japan’s political influence with Philippine elites. Furthermore, Duterte’s strategy of distancing from the United States and rapprochement with China risks undermining emerging U.S.-Japan-Philippine security cooperation.

On the upside, these developments provide Abe with the domestic political justification to boost state-backed funding to the Philippines, while pressuring and incentivizing Japanese companies to double-down on investment. More importantly, the current rift and future uncertainty over U.S.-Philippine relations presents Tokyo with an opportunity to exercise leadership in the ongoing effort to evolve the U.S. hub-and-spoke security alliance in Asia into a more multilateral and interoperable system with increasing spoke-to-spoke linkages.

If the Trump administration turns inward and withdraws from upholding the rules-based order in the Asia-Pacific, Japan will need to become more self-reliant and take on a leadership role and increased burden-sharing. However, without decisive U.S. leadership and commitment (the “hub”), U.S. allies and partners (the “spokes”) will be limited in what they can accomplish alone or among themselves in the face of a resurgent and assertive China.

Jeremy Maxie is an Associate at Strategika Group Asia Pacific. He tweets at @jeremy_maxie. This article has previously been published on the EastWest Institute Policy Innovation Blog.