For fugitives from Chinese justice, good hiding places in Europe are getting fewer and further between. France’s extradition of Chen Wenhua from Paris to Beijing in September 2016 was widely celebrated by Chinese media and officials alike. The official from Zhejiang province was sought back home for embezzling funds totaling 2.7 million euros ($2.9 million). In the context of China’s current massive anti-corruption campaign, he is a small fry, but Chen’s arrest and extradition marked a success of China’s “Operation Skynet,” which has the goal to chase so-called “economic fugitives” abroad – and it was the first application of a Sino-French extradition treaty, which France had ratified in April 2015.

The case received only limited public attention in Europe, which could turn out to be a mistake. Cases like Chen’s deserve further debate as they illustrate the potential pitfalls of law enforcement cooperation with China. While corruption is a crime in other legal systems as well, China’s anti-corruption campaign is driven by the ruling Communist Party, leading to blurry lines between political and judicial prosecution.

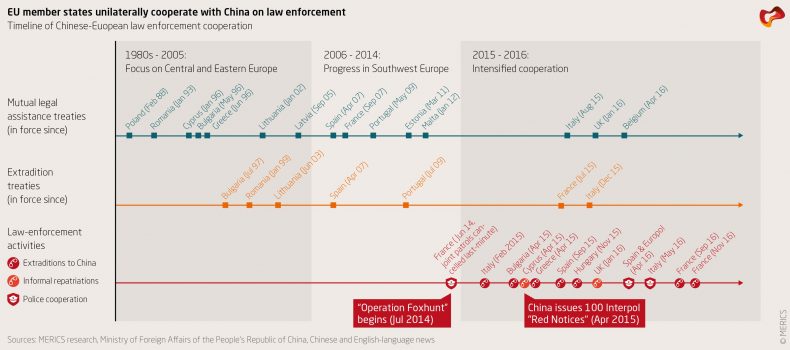

France is not the only European country that has extradited criminal suspects to China. Since 2015, five other EU member states have extradited “economic fugitives” upon Beijing’s request. Hungary and Greece have extradited suspects in the absence of formal extradition treaties, and informal repatriations are known to have taken place from the U.K. and Cyprus. To date, seven EU member states have signed and ratified extradition treaties with China: Bulgaria, France, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Romania and Spain. Apart from that, a number of EU members have mutual legal assistance treaties or agreements on police cooperation or combating cybercrime.

As even more European states are negotiating and entering police and judicial cooperation agreements with China, there is an urgent need for defining common standards and red lines. Just as the EU strives to better coordinate its fight against terrorism and organized crime internally, intra-European coordination should also be the basis of increasing law enforcement cooperation with third countries such as China.

In an age of increasing cross-border crime, European governments have a clear interest in working closely with China. China has become a hub for transnational crime like drug trafficking, money laundering and cybercrime – and Europe stands to gain from joint action against such cross-border offenses. Economic interests are also at stake: Italy’s decision in 2016 to allow China to station patrol officers in Milan and Rome is meant to address Chinese tourists’ concerns about their safety in Europe, ranging from street burglaries to terror threats.

Yet police and judicial cooperation with China raises difficult questions, especially with regard to extradition requests. Contrary to official Chinese assurances, the basic right to a fair trial is not protected in China. Torture and forced confessions remain common practice, and economic crimes can carry drastic penalties (up to the death penalty).

An increasing number of cases around the world show how China uses its economic leverage to pressure other countries to agree to controversial extraditions. Recent examples include Kenya’s extradition of 45 citizens of Taiwan to mainland China in April 2016, or the forced repatriations of ethnic Uyghurs to China from Central Asian and Southeast Asian countries – often coinciding with Chinese investment pledges in the extraditing countries.

Such politically sensitive cases may seem less likely to occur in Europe, since extradition treaties between EU member states and China generally contain strong safeguards. For example, Western democracies demand guarantees that extradited suspects will not be subject to torture or the death penalty at home.

Last but not least, extradition requests from China can raise thorny questions for international diplomacy. The Kenyan case exemplified the pressure exerted by Beijing to obtain symbolically important extraditions (even in the absence of an extradition treaty), which help to buttress its claim to exert jurisdiction over all residents of Taiwan.

Spain currently faces a similar dilemma. Spanish police arrested more than 200 suspects in a transnational phone scam with the help of mainland Chinese police. China is now demanding the extradition of all subjects, including those who hold passports from Taiwan, based on the Spanish-Chinese extradition treaty. For European nations like Spain that have official diplomatic relations only with China, but also maintain informal relations with Taiwan, this case presents a particular diplomatic headache.

It is high time for the EU to develop a strategy for cooperating with China in these areas, rather than each member state going it alone. European governments need a consistent common position on demands for judicial reforms in China or for even stronger safeguards. This is the only way to prevent bilateral agreements with China from undermining international legal norms and democratic values.

Thomas Eder and Bertram Lang are Research Associates with the European China Policy Unit, Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) in Berlin.