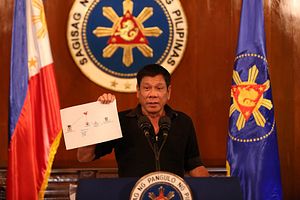

At about noon on January 18, Philippine time, just days before United States President-elect Donald Trump took his oath of office, another strongman of a much smaller nation, the Philippines, addressed his citizens in a speech at Cabanatuan City. He took aim at the Catholic Church, which recently condemned his war on drugs. Claiming that his crusade against narco-politics is a god-given quest, Duterte vowed that the killing will not stop “until the last pusher is out of the streets.”

Unlike Trump’s victory, Duterte’s statement was unsurprising. Rooting out the issue of drug usage through forceful means was one of the key platforms that led him to the Malacañang Palace (the Philippine equivalent of the White House). What is surprising is the widespread public support for this policy in the face of gruesome human rights abuses and clear subversion of any legal processes. While it is too early to make a definite conclusion about the success of Duterte’s war on drugs, we can reflect on the United States’ successes (or, more accurately, its failures) when President Richard Nixon declared drug abuse “public enemy number one” in 1971 and sparked the “war on drugs.”

The results since have been mass incarceration, increased corruption, political destabilization and violence, and, above all, the loss of liberty. Misguided drug laws and a draconian system of sentencing have led the United States to house nearly 25 percent of the incarcerated population of the world despite having only 5 percent of the world’s population. Furthermore, the war on drugs actually increased drug production and transport as well as violence in Latin America. Ultimately, the war did not complete its stated goal of curbing drug trafficking, but instead exacerbated many other issues around the world.

Nixon’s war on drugs failed for the most part because it ignored a fundamental economic principle: the law of supply and demand. While there are demand-side penalties in the form of unreasonably harsh punishments towards drug users, the U.S. war on drugs is primarily a war on the supply side. At its core the war acts like a tax on drug suppliers: it increases the cost of production of the good and thus disincentivizes dealers from supplying drugs. The result of this in any other market would be a decreased consumption of the good as well as an increase in price. However, the consumption of narcotics is not price sensitive — Drug users will continue to consume close to the same quantity even at an increased price, as well as the added-on risk of imprisonment. The war on drugs actually increases the incentive of drug producers to continue or even enhance production as they can charge more for their products and thus stand to gain more revenue.

Drug prohibition may decrease consumption to an extent, but it can be argued that it disproportionately increases the destruction drugs can cause to a society. In his book The Economics of Prohibition, American economist Mark Thornton found that making drugs illegal forces drug producers to make them more potent and smaller in order to minimize their risk of detection. Furthermore, it shrinks the price differential between more potent and less potent drugs since the cost of evading law enforcement is fixed regardless of potency. This means that the war on drugs actually encourages drug users to consume more dangerous narcotics, which makes them more threatening individuals. Moreover, it forces addicts to resort to crime to afford to pay for their habit, making a country more insecure than it was before. Drug prohibition also drives narcotics businesses to resort to violence since they cannot settle disputes in court. Economist Jeffrey Miron states in his book Drug War Crimes: The Consequences of Prohibition that drug prohibition has increased violence by 25 to 75 percent in the United States. At its core, the American war on drugs was a misguided strategic failure that enhanced the issues of drug production and consumption in the United States.

While the stage is different, the basic principles of Duterte’s drug war remain essentially the same, albeit with some caveats. If Nixon’s war on drugs failed because the United States disproportionately targeted supply over demand, Duterte has an answer: kill the drug addicts. If users continue to consume narcotics despite government intervention, then Duterte and his most ardent supporters believe that their eradication is a necessary response to reach their end goal of a more secure, safe Philippines.

The proposition that it is preferable to exterminate human beings rather than provide them the resources to rehabilitate themselves is nonsensical. Drug abuse is a public health issue that hasn’t been effectively addressed by any president, and Duterte’s kill-all solution has only led to division among the Filipino people and an increased overall distrust in law enforcement. The 1,027,862 drug abusers and producers that have surrendered themselves to the Philippine police are doomed to relapse in some form or another if there are no services to assist them.

The Philippines is at a crossroads. Years of distrust against a political system that has perpetuated elite rule allowed an “outsider” to rise above with the hopes of permanently changing Philippine institutions. However, Duterte is no different than the leaders before him, and he may in fact be more dangerous. His willingness to undermine the fractured judicial system through his drug war instead of working on its reform is a political project that contradicts the fundamental aims and values of a true democracy. His statement that “no one can stop [him]” from declaring martial law is bone-chilling, and his overzealous support of the Marcos family is not something to be taken lightly. When the rule of law plays second fiddle to the systematic violation of rights there is reason to be afraid, even when the target is considered “undesirable.”

Alec Regino is a Filipino Sociology major at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. He is particularly interested in international affairs, South-east Asian politics, international security, and foreign policy.