An article in the Wall Street Journal toward the end of December 2016 described several Chinese sources as saying that Chinese President Xi Jinping “‘wants to keep going’ after 2022 and … explore a leader structure ‘just like the Putin model.’”

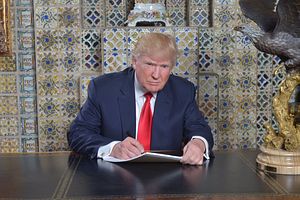

Coming on the heels of the election of Donald J. Trump in the United States, of Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, and the continued consolidation of power by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey, it is clear that several major countries are marching at an increasingly accelerated rate toward the political phenomenon known as “Putinism,” or sometimes as “Trumpism.” This is happening both in Asia and the rest of the non-Western world, where liberal democracy is less deeply rooted, as well as in the West.

Is Putinism a path that more nations are increasingly likely to go down on in the present century, rather than being a temporary phenomenon? And if so, why is this the case? The lessons of history suggest that similar phenomena have occurred at periods of upheaval, change, or complexity in human history, such as during the transition of the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire during the rule of Augustus, the rise of the Umayyad Caliphate, or the unification of China under Emperor Qin Shi Huang.These represent the consolidation of power in strong individuals or dynasties after periods of more dispersed leadership.

While Putinism has been described in many ways — including nationalism, alliance with religion, social conservatism, state capitalism, and government domination of the media — at its heart, it is autocracy based on populism, and the personalization of political power in an individual. In increasingly bureaucratic and complex societies, many people seek a leader with whom they can forge a “powerful, personal connection,” as David Bell, writing for Foreign Policy magazine, put it.

This is especially true in societies that have recently modernized, such as Turkey or China, where pre-modern power relationship patterns are still a familiar memory. Leaders are perceived not necessarily as public servants but as father-figures who treat their societies as extended families. It is not surprising that in times of increased globalization, ethnic conflict, and uncertainty about the world order, the peoples of various countries are reverting to that sort of thinking.

As medieval Islamic political thought attested during the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, the most important thing is to have a strong, charismatic, and decisive leader, rather than merely a just or “by the books” one, so as to lay the foundations of a secure and prosperous state. Such a leader can constantly appeal to the masses in order to change the direction of the state; personalization, then, isn’t always a bad thing. After all, for every Stalin, there is a Peter the Great.

Thus, the phenomenon of the modern strongman, now being emulated in the United States and China, is deeply rooted in history and human social need, and is basically a modern manifestation of the same impulses that led to kingship in ancient times, though today it may not be as hereditary. Recall that it also took many years for hereditary monarchy to emerge from a more loose sort of kingship. In modern times, it is likely that this second type of more loose kingship will be the norm.

According to the book War in Human Civilization by historian Azar Gat, in ancient tribal societies on the cusp of transitioning into complex states after the development of agriculture, there arose various “big men.” The status of such an individual “derived from… social astuteness and entrepreneurial spirit, charisma, prowess, and skillful use of… property.” Additionally, “he offered patronage and protection, economic assistance in times of stress, and benefits in general… in return he received… subordination and support.” Eventually power, status, and wealth accumulated and there arose what was essentially a “nascent aristocracy.”

It is likely that any system over time will be gamed by those deploying their charisma, wealth, and patronage to influence a large number of people. Thus, it is no fluke that some sort of monarchy or authoritarianism has been the rule throughout most of history. And while private interests may drive this phenomenon, there is also a strong element of public desire for a larger-than-life patron.

The world is too complex and humans not dispassionate enough for liberal democracy and strong institutions to always work out and take hold. Political systems are now reverting to their “natural” state. It is not surprising to see Trump and Xi (and perhaps one day, successors of Modi and Abe) working off of the “Putin Model.” Perhaps this is humanity’s destiny in the 21st century, not liberal democracy and strong institutions. If this is to be the case, then, the focus of those who value fairness and justice should be to develop those values within these emerging systems, by encouraging the adoption of just norms and practices.