When USSR disintegrated in the beginning of the 1990s, it was not because of a war or other external pressure. Nor did it collapse under its own economic weight — arguably, this vast country had enough natural resources and cheap labor at its disposal to convert them into economic growth without market economy forces, at least for some extended period of time. The Soviet empire fell because the center let go of the periphery.

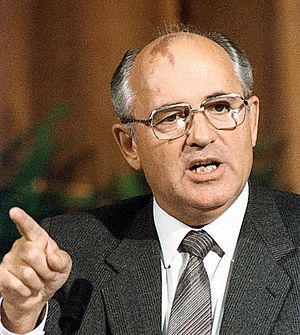

The fall had started long before the actual disintegration, when fewer and fewer people genuinely believed in the Soviet ideology and raison d’être. But it took Mikhail Gorbachev, the last secretary general of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and his “perestroika” to bring these processes to a boiling point. Quick to recognize how corrupt the system was, Gorbachev embarked on his radical reforms.

From our historical fait accompli point of view, we know that ultimately Gorbachev’s perestroika failed; it set in motion a chain of events that could have only ended with the destruction of the Soviet empire. The complexity of the system simply did not allow for some of the key elements to be reformed without collapsing the entire edifice. From his own point of view, however, all that Gorbachev wanted was to make the Soviet Union “great again.”

Despite the vast differences between Donald Trump and Mikhail Gorbachev — both in terms of personality and in terms of actual reality they faced — there are striking similarities in the structural settings for their actions, and their potential unintended consequences.

First, the differences: Gorbachev presided over a true “empire of evil,” driven by ideological fanaticism, economic determinism, and political oppression, while the United States is a capitalist liberal democracy. Gorbachev was a career apparatchik and a sincere believer in the virtues of communism; Trump is a businessman with no prior political experience, whose belief in capitalism is perhaps the only certain characteristic of his.

Yet, both professed a desire to reform stunted political systems and obsolete military alliances; they both want to “drain the swamp.” In the case of Gorbachev, that meant ousting the octogenarian career politicians, who had usurped power and monopolized the policy space, not allowing fresh blood to stream in. For Trump, the “swamp” means a rigid political system corrupted by special interests and big companies’ lobbying. More pertinently, they shared a belief that the systems they presided over were rigid and hard enough to sustain the shock from their respective reforms.

Gorbachev was wrong. Now Trump’s Gorbachev moment is upon him, and he will be well-advised to consider the grave dangers for the future of the United States his reforms hide.

Gorbachev’s goal, after he came to power in the spring of 1985, was to jiggle out the “deep state” from its hardened and corroded condition of lethargy, to shake the establishment out of its affected ease and comfort with the explicit promise “to return the power back to the people.” At that time the economy was failing –GDP growth was less than 1.6 percent while the Soviet public debt was skyrocketing — the communist ideology was no longer hegemonic, and the propaganda was unable to keep up with the penetrating force of the American soft power thanks to technology and globalization. The Warsaw Pact, the military alliance established in the mid-1950s to counter NATO’s deterrence power, was largely dysfunctional, with its member states forced to recycle old Soviet military equipment and pay prime prices for it. Most importantly, a growing number of disillusioned people all across the communist bloc held deep resentment of the political status quo, not only because communism turned out to be a monstrous ideological system, but also because its economic model had stopped delivering results.

Trump faces similar risks today with regard to the post-World War II liberal democratic order America has helped build. Like most Western economies, the American economy today too is affected by automatization, globalization, and the export of unskilled jobs to countries like China, Vietnam, Indonesia, India, Mexico, and Brazil. The growing inequality gap has squeezed the middle class – the economic engine of progress and prosperity, and a source of political stability – and the liberal democratic model no longer delivers benefits to them. Public debt is at an all-time high, while the trade deficit with “emerging economies” is growing.

As a remedy to all that, Trump wants to bring back protectionism and to halt globalization. He questions NATO’s “shared values” raison d’être and has threatened to loosen the U.S. commitment to “peripheral” member-states, such as the Baltic and the Balkan countries. In essence, he advocates for a return to the historical model of military alliances, which appeared whenever they were needed and ceased to exist whenever the need was no longer there. Trump also wants to transfer the costs for maintaining the alliance onto those who need the American protection the most – Japan and South Korea being the prime examples. Perhaps most troubling though, while remaining committed to the “democratic” part of the American liberal democracy, at least in words, he openly questions the “liberal” part, with incessant attacks on civil and human rights.

For what is worth, some of Trump’s skepticism is justified. China’s vital economic role in the U.S. and global economy has so far prevented American policymakers from reining in Chinese advances in the South and East China Seas. The EU’s 500-plus million common market, which was made possible largely thanks to the decades of enjoying the U.S. security umbrella, is ostensibly eating away at American commercial and economic global prowess.

The “liberal democratic order” the U.S. helped institute after World War II is fast losing its steam, both domestically and abroad. It delivers economic growth outside but is not capable enough to keep dictatorships in disguise in a straight jacket. Worse, the system does not deliver at home, effectively depleting the semantics of concepts such as “freedom,” “equality,” and “democracy” itself.

As a result, democracy is no longer a hegemonic paradigm among non-Western states, and a wave of de-democratization is even creeping into some Central and Eastern European states. Worst of all, no one today, not even the United States, is willing to sit in the leadership seat of the global liberal democratic order, to take responsibility and to foot its bill. It is, in the words of one commentator, a truly “G-Zero World.”

Trump’s radical solution for many of these issues is to go “back to the future”: to return to protectionism in order to revitalize dying industries and bring jobs “back to America”; to change NATO’s modus vivendi and alter the Asia-Pacific strategic military alliances’ core modus operandi, returning to a 19th century balance of power system; to weaken the EU’s integration trend in recognition of the obvious fact that not China or Russia, but rather the EU, is the largest economic competitor to the U.S. today; and to put greater pressure on China. Trump’s “perestroika” may prove to be as radical to the 70-plus-year-old American liberal democratic order as Gorbachev’s original one was to the then 70-year-old Leninist communist order.

Trump’s radical worldview captures the urgency for a wholesale transformation of some of the core principles of the liberal democratic model. Unfortunately, it focuses on the wrong reforms. A return to protectionism and nationalism will not bring back the lost steam of the American economic system. Rather, it would speed up the process of social disintegration, polarization, and strife. In the meantime, America’s retreat from global leadership will open doors to underdogs like China and Russia, which will be all too happy to fill in the political vacuum with their own visions for the world order. To be sure, neither China nor Russia’s plans seem to include a “make America great again” component.

Trump is fast following in Gorbachev’s footsteps today. He too is a champion of a growing multitude of disillusioned supporters, many passive and hard to detect, but who may rise as a tidal wave to sweep away the remnants of the dominant order. He, too, wants to let the periphery go in an attempt to save the core. But, unlike 1989, when the alternative to communism was the liberal democratic model, today no such alternative is readily available. This is the gravest danger from misreading or misacting on the Trump’s Gorbachev moment. In such ideological and political vacuum spaces monsters usually live, waiting their moment to come out.

Liubomir K. Topaloff, Ph.D, is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the School of Political Science and Economics, Meiji University.