Professor Joseph Nye Jr. raised an important new concept of the “Kindleberger trap” weeks ago. It follows late MIT professor Charles Kindleberger’s classical arguments that the Great Depression in the 1930s was caused by the shortage of global public goods provision when the isolationist United States refrained from assuming the responsibility while the Great Britain lost its capability to play the role. Nye thus cautions the American leaders to be wary of a China that seems to be too weak to take international responsibility rather than too strong as the now popular concept “Thucydides Trap” implies.

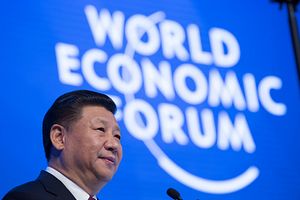

This new warning deserves close attention. It reminds us that global order cannot function efficiently without sufficient public goods provision from powerful states. However, we must also note that the reality today also diverges significantly from the 1930s. In fact, the actual challenge now is not that the established power has lost its capability while the rising power is unwilling to assume responsibility. Instead, as shown by President Donald Trump’s isolationist “America First” inaugural address and President Xi Jinping’s pro-globalization speech in Davos, the current situation is much more that the established power still enjoys power superiority but refuses to assume its responsibility while the rising power is eager to play a greater role but still lacks sufficient capability.

Under the presidency of Donald Trump, Washington is now managing to cut its commitments in areas like free trade and climate change, while asking other states, its allies in particular, to shoulder more burdens. The new president has openly pledged to take America back to a nativist era. This is not just about his personality, however. Trump’s election reflects a widespread frustration among American voters on their country’s involvement in global affairs in past decades. Trump and his followers thus strongly believe that the president must put “America first.” This change never means the abandoning of American supremacy in the international system. Instead, just as happened in the George W. Bush era, it is exactly continued unrivaled American primacy that gives Trump both incentive and capability to play the unilateral game.

With Washington possibly retreating from global governance, a new round of the debates has emerged within China after the G20 Hangzhou summit and Xi’s speech at Davos. A number of officials and analysts expect that a window of opportunity has opened up in China’s quest for a greater role or even leadership in global affairs. Nonetheless, another group of analysts seriously cautions the danger of over-commitment. They strongly warn that for China, as a developing country with pressing domestic problems, talk of global leadership is premature and ill-timed. It would waste valuable resources for domestic economic growth and social warfare improvement while attracting unnecessary obstructions from other countries. Thus, while many Western observers, Nye for instance, are worrying that Beijing will “free ride,” many leading Chinese analysts are concerned more about their country’s growing risks of “strategic overdraft.”

Given the above incentive-capacity imbalances in both the U.S. and China, it is possible that the world might experience a dark decade like the 1930s again. How can the world prevent this worst-case scenario? Above all, it should be clear that the main responsibility to avoid the “Kindleberger trap” lies not on Beijing but Washington. Meanwhile, China should stay humble and strike a balance between global inspirations and domestic needs. To fulfill a greater international role, above all, China’s own domestic governance needs to be further improved in many areas like transparency, efficiency, and fairness. Better serving a country that is home to one-fifth of all human beings is the top responsibility and the greatest contribution that the Chinese government could offer for global governance.

Meanwhile, domestic weakness should not stop China from acting more constructively in global governance. In the past decades, China has become an active participant in the existing global governance regimes, through which China accomplished the twin goals of economic growth and political stability. An open, stable, and institutions-based global order is in China’s interests and it should be ready to cooperate with other powers like the EU and other BRICS states to fill the gap of public goods provision and force Washington to return to the multilateral track.

Moreover, further global engagement could also help to promote China’s domestic reforms in some constructive ways. For instance, against the Trump challenge, Chinese could make significant efforts in at least two important issue areas of global governance. One is free trade. The Trump administration’s aggressive anti-free trade stance, including the abandoning of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), has made both great necessity and opportunity for China to embrace a more influential role in free trade promotion. China’s economic development still badly needs foreign resources and markets; meanwhile, other countries also need the huge opportunities an open China could offer. Beijing should accelerate the negotiation of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) to counter emerging protectionism in the region. Further opening up and high standard free trade agreements would also help to facilitate Chinese domestic reform, which now desperately needs new momentum (like that provided by joining the WTO in 2001).

China can also take on global leadership to boost its domestic shift toward green and sustainable development. Nowadays, China faces severe environmental pressures. Trump had revealed his intention to pull the United States out of the Paris Agreement. Beijing must not follow. Instead, it should resolutely increase input on new energy sources and green development. This would allow China to step up as the new champion of climate change. International commitments would also push further developments of government capacity in relevant areas.

In a word, we must avoid a dichotomous understanding of China’s relations with global governance. China has greater international responsibilities to shoulder in accordance with its growing power, but this does not necessary mean global leadership. The obstacles for China’s more active role in global governance come firstly from its domestic weakness. On the other hand, through more comprehensive and creative strategies in engaging international institutions, it is possible for China to deal with domestic and global governance challenge simultaneously.

Dr. CHEN Zheng is Oxford-Princeton Global Leaders Fellow of the Global Economic Governance Program, University College, University of Oxford. He is also assistant professor of international relations at the School of International and Public Affairs, Shanghai Jiaotong University.