Four months after a retaliatory counterinsurgency campaign plunged Myanmar’s western coast into the depths of a humanitarian crisis, the government suddenly, and without much fanfare, declared the military operation over as of February 9.

For beleaguered Rakhine State and the tens of thousands of Rohingya Muslims displaced by the recent violence, this cessation marked a barely perceptible shift in a long entrenched conflict. For the military and the police personnel who continue to be deployed along Rakhine’s northern border – which remains subject to a lockdown and has reportedly been lashed with fresh attacks – it appears to denote a change in scale, if not in character. In fact, with the three-hour relaxation of the curfew signifying the most drastic alteration, one might be forgiven for not noticing the campaign’s end at all.

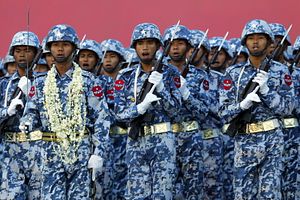

From October 9 through February 9, police and Myanmar’s military – known as the Tatmadaw – launched a thundering joint operation in response to deadly attacks on border guard posts, attacks that were believed to have been orchestrated by a foreign-funded insurgent group. The brutality of the operation provoked international outcry, while raids carried out against civilian villages under the auspices of militant “clearance operations” begged the question of the campaign’s intended aim.

By the time the campaign’s conclusion was declared, the onslaught had not just failed to root out the Rohingya insurgency, it galvanized the organization’s cause, training an international spotlight on the plight of a largely defenseless community. Through hounding villages with regular sweeps, helicopter raids, and alleged, large-scale arson, the clearance campaign propelled more than 100,000 Rohingya villagers from their homes, leaving only razed remnants and stories of “devastating cruelty” behind.

“The 9 October attacks appear to have given the security forces the perfect cover to amplify and accelerate actions they had previously carried out through policies, rules and laws – with the apparent objective of expelling the Rohingya population from Myanmar altogether,” Yanghee Lee, the UN special rapporteur for the situation of human rights in Myanmar, said in a statement released on February 24.

Both the Myanmar government and Tatmadaw officials have denied that the campaign intended to eject the Rohingya from their enclave in northern Rakhine State. Government spokesperson U Zaw Htay would not directly respond to the special rapporteur’s allegation, but said, “We are very serious about the situation of Rakhine State… there are many commissions trying to find out and clarify the real information. If there is concrete evidence of abuses we will take action.”

But even as the government promises to restore stability to the volatile strip in the wake of the “clearance operations,” UN officials have revealed that there is currently no government-backed plan to repatriate the more than 74,000 Rohingya who fled to neighboring Bangladesh, or to help resettle the 24,000 believed to be internally displaced within Rakhine State.

“While some of the new arrivals in Bangladesh have said they will return home if and when it’s safe, I’m not aware of any government plans to facilitate it at this point,” said Vivian Tan, a spokesperson for the UN refugee agency.

For the nascent National League for Democracy government almost a year into its administration, there’s no domestic political capital to be gained in negotiating the return of a long-reviled population. Much of the country perceives the Rohingya – commonly called Bengalis – as illegal interlopers from the Muslim-majority nation next door. But for the NLD, grappling with criticism over Rakhine on the international stage has been another matter entirely.

Bangkok-based security consultant Anthony Davis recently wrote that the counterinsurgency campaign in Rakhine State “has arguably been the most serious public relations debacle suffered by the Myanmar military since its massacre of pro-democracy protesters in 1988.” And unlike when the military junta ran the show, the democratically elected government has now been forced to shoulder a large portion of the condemnation.

Many observers believe the government only endeavored to declare an end of the clearance operations in order to alleviate international pressure as momentum builds for an UN-led commission of inquiry into allegations of crimes against humanity in Rakhine.

“Myanmar has proudly claimed the clearance operations have ended, as if we’re somehow supposed to look past the mass gang-rape, mass killing, and widespread arson attacks. We believe the government is touting the end of the clearance operations to try to persuade the international community to not mandate a Commission of Inquiry,” said Matthew Smith, co-founder of human rights group Fortify Rights. “The reality is that the Rohingya have been living through so-called clearance operations for decades.”

But as the Human Rights Council convenes in Geneva, with the special rapporteur expected to deliver both a report and a recommendation for an inquiry on March 13, security forces do not appear to be decamping from northern Rakhine.

In fact, it remains unclear if the Tatmadaw, which does not fall under civilian authority and still retains a sizeble political role, even agreed to terminate the crackdown.

The day after presidentially appointed national security adviser U Thaung Tun – a civilian – declared the campaign over, Tatmadaw spokesperson General Aung Ye Win provided an alternative perspective. He told local news site The Irrawaddy, “We will not stop clearance operations. There will be regular security operations. Ceasing military operations is information I am not aware of.”

Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division, said the denouement announced by the government reeks of opportunism.

“This announcement looks a lot like the traditional Burmese charm offensives of old, trying to spin out some positive news before the Human Rights Council takes the government to task on its poor human rights record,” he said. “On the ground, the reality unfortunately hasn’t changed that much: the so-called ‘clearance operation’ areas in northern Maungdaw [township] are still heavily militarized, independent monitors are [still] shut out of the area, and the Tatmadaw still uses scorched earth tactics that treat the lives and well-being of vulnerable villagers as acceptable collateral damage in the pursuit Rohingya insurgents.”

Sealed off from journalists, humanitarian aid workers, and outside observers under the pretense of security concerns, the operation areas of northern Rakhine State remain just as inaccessible in the twilight of the counterinsurgency campaign. Despite a deluge of allegations about abuses perpetuated by the soldiers and police, the accounts continue to be impossible to verify on the ground. Meanwhile, the government has deviated little from issuing blanket denials and promising investigations, responses which UN officials have alternately deemed “callous” and not credible.

Rights workers have instead documented the alleged atrocities from next door, in the refugee camps on the fringes of Cox’s Bazar.

Rohingya have swelled over the porous border with Bangladesh for decades. In northern Rakhine State, even at the best of times the Rohingya lived in an “occupation zone,” where they are denied citizenship, freedom of movement, and access to higher education and health care, and periodically subjected to immigration crackdowns. In Bangladesh, they do not find a drastic improvement.

Dhaka estimates some 300,000 Rohingya Muslims are now taking refuge in Bangladesh, including more than 74,500 recent arrivals. Of those, only 34,000 are registered in two officially recognized camps, so only they are eligible for official humanitarian aid, such as food subsidies and housing. The rest have no legal status, and are forced to improvise an existence by scavenging and begging off those who have little to share.

“For decades, Bangladesh has deliberately deprived Rohingya of adequate humanitarian aid. It’s a grisly, inhumane policy. The authorities in Bangladesh need to get over themselves and understand that Rohingya aren’t being pulled out of Myanmar by the prospects of prosperity in the camps – these are some of the world’s worst refugee camps,” said Matthew Smith of Fortify Rights. “The authorities’ avoidable deprivations in aid haven’t prevented Rohingya from fleeing to the country. Rohingya have only ever been subjected to brutal push factors.”

A landmark UN OHCHR report released at the beginning of February concluded that the widespread allegations of abuses, including murder, torture, and rape, committed by soldiers and police, indicated “the very likely commission of crimes against humanity.” Of the 204 Muslim Rohingya who were interviewed in Bangladesh, the vast majority reported witnessing killings. Of the 101 women interviewed, more than half reported having suffered rape or other forms of sexual violence.

Following her own visit to the refugees in Bangladesh, special rapporteur Yanghee Lee said what she heard was even worse than she had anticipated.

“I heard allegation after allegation of horrific events like these – slitting of throats, indiscriminate shootings, setting alight houses with people tied up inside and throwing very young children into the fire, as well as gang rapes and other sexual violence,” she wrote.

While rights workers say that Bangladesh understands the severity of the situation and has agreed not to push involuntary returns for now, the country is also increasingly reluctant to play host. Dhaka has said that the additional refugees are straining an already overtaxed system, and fueling narcotics and trafficking gangs.

Bangladesh insists that as Rohingya Muslims are from Myanmar, they must return across the Naf river marshlands.

Though past influxes have subsequently been repatriated, some in arrangements brokered officially by the UN, the unprecedented level of violence experienced in the recent crackdown as well as the lingering military presence in northern Rakhine State, prevents many from looking back.

“That military operation might have ended, but the oppression of the Rohingyas in Burma has not,” Dil Mohammad, a 30-year-old living in a shantytown in Cox’s Bazar told VOA, adding that he believes the vast majority of those who fled the recent crackdown will not return.

As an alternative, Bangladesh has proposed a controversial scheme to relocate the refugees to Thengar Char, a flood-prone and underdeveloped island three hours by speedboat from any other habitation. Whether the island is fit for human occupation is a matter of debate even within the Bangladeshi government, with a local forestry office citing a lack of drinking water and frequent natural calamities such as cyclones.

UN officials appear to have dismissed the island plan as an abstract proposal, while others have slammed it as a dangerous non-solution.

“The idea floated by the government of Bangladesh to force recently arrived Rohingya onto an island particularly vulnerable to flooding is completely unacceptable. It has been denounced and abandoned in the past and I’d expect that to be the case again now,” said Daniel Sullivan, a senior advocate with Refugees International.

But Dhaka isn’t moving past the plan so swiftly, and has reportedly asked both the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and German Chancellor Angela Merkel for assistance in carrying out and funding the island proposal. Foreign ministry officials have at least acknowledged that the relocation could not be carried out until infrastructure is developed.

For now, the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh do not appear to be going anywhere. How long that lasts, especially if they refuse repatriation, is a matter of no small concern.

“While the international spotlight is still on the Rohingya, Dhaka is tolerating the influx, but when that attention moves to another part of the world, expect things to change fast,” said Phil Robertson of HRW.

“Bangladesh is like most of the governments in the region that just want the Rohingya to be someone else’s problem.”

Laignee Barron is a journalist and editor based in Yangon, Myanmar. You can find her on Twitter @laignee.