Anyone focused on the three main international initiatives associated with China in the last two years will notice something puzzling about them. The first is the Belt and Road Initiative. There is no formal government map of this, spelling out the countries involved. But the idea does seem to be seeping into all areas of the globe. Maps of locations along the sea and land routes created on the basis of information from the official news agency Xinhua (here’s an example from the Council on Foreign Relations’ website) show how deeply into the Asia Pacific, Central Asian, and European regions the routes run. It looks like a truly global concept.

The same can be said for the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, (AIIB) set up in 2015 amidst much controversy, with the U.K., Australia, Germany, and a host of other nations across the world signing up. This amounted to 56 founding partners. Once more, within this membership one can divine the potentially epic outlines of Chinese global ambitions and intent.

There finally there is the map of RMB trading centers and places with currency swap deals with China. There are over 25 of these across the planet now, running from Sydney and Singapore to London, Paris, and Frankfurt, and finally reaching across to Toronto, South Africa, and Chile. As with the Belt and Road Initiative and the AIIB, the list of countries that have signed bilateral deals delineates some sense of China’s global reach (a list up to January 2015 is here). Latin America, Africa, Central Asia, Europe, Oceania — everyone seems to be included.

But there is a strange omission, made even more glaring when one maps out the locations involved in these three separate initiatives. The Belt and Road Initiative might have pushed into every corner of the globe, but there is one destination it has assiduously avoided – the United States. The same goes for the AIIB, an entity that former President Barack Obama pointedly refused to contemplate joining. As for currency swap deals, it is true that in late 2016, finally, a bank in New York gained permission to clear Chinese money. But in view of the size of the U.S. financial market and economy, it should have been the first on the list – not among the last.

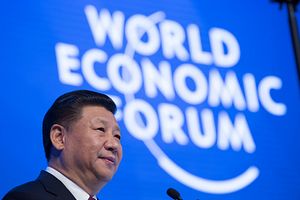

These three great arrows illustrating Chinese contemporary global ambition speak volumes in their lack of any grand role for the United States. It is perhaps the most revealing thing about them. Under Xi Jinping, the principal aim of China’s overseas push almost seems to be drawing a world where America is circumvented, marginalized, and dreamed away. This is pushback against the decade under Hu Jintao, when China’s primary complaint was U.S. containment. The door to liberty has been found – through, as one African diplomat at a 2014 conference I attended in Beijing put it, subtly, carefully, and very deliberately staking out areas where China knows the United States can complain, but not intervene or shout too much. Finally, the solution to the dreaded Thucydides Trap has been found: build massive links stressing economic common ground, but exclude the world’s largest economy on the grounds that it is too grand and important to get involved. And up until recently, this strategy has largely worked.

In this context, the spoilsmanship of China’s perennially pesky neighbour North Korea over the last few weeks becomes particularly piquant. For Chinese analysts, it is almost as though there is a hotline from Pyongyang to Washington, with a subversive deal done for the ailing Kim regime lure the United States — poised under new President Donald Trump to partially extricate itself from the Asia-Pacific — straight back in.

The greatest frustration in Beijing about North Korean antics since mid-March will be that at a time when it finally looked like China was going to be offered yet more space to occupy away from the United States, America is back in the region with a vengeance. Almost half a decade of patient work and delicate diplomatic maneuvering to create a world of legitimate Chinese activity and influence away from the United States looks to be in peril because of the attention-seeking work of China’s impoverished neighbor.

This, more than anything else, may well be the reason why Chinese officials are considering what was once unthinkable – finally closing down the space on their one treaty ally. When scholars as seasoned as Shen Zhihua publicly upbraid the Xi government for being soft on Pyongyang, and urge it to walk away, then changes are afoot. The simple fact is that North Korea has taken aim at China’s Achilles’ heel – its desperate search for strategic space where the United States will leave it alone.

The poet W.B. Yeats famously warned to tread softly when treading on others’ dreams. The China Dream never stated this outright, but part of its aim was clearly getting away from the United States. And North Korea at the moment is standing in the way. Pyongyang may well be about to find out just how much China wants this moment of liberty. In 1950 North Korea scuppered Beijing’s chances of claiming Taiwan. This time China is not going to be made to look a sucker again.