As Chinese loans pour into Latin America, concerns over how the money is spent and how it will be repaid are growing on both sides of the bargaining table.

Of most immediate concern for China is whether economically unstable governments such as Venezuela can pay back multi-billion dollar loans amid globally low prices for crude oil.

By the close of 2015, China held $53 billion of Venezuelan debt. However, U.S. think tank Inter-American Dialogue suggests that figure could be as much as $65 billion. Despite Venezuela’s deepening recession, China has continued to lend, offering $2.2 billion in November 2016 alone.

“Many thanks for all the support you have given Venezuela in 2014, 2015, and especially 2016. Our older sister China has not left Venezuela alone in moments of difficulty,” said Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro in a televised speech.

But the changing global economic environment means that China cannot continue lending to Latin American countries worry-free. Analysis by Inter-American Dialogue shows that in 2016, 92 percent of China’s loans to Latin America went to Ecuador, Venezuela, and Brazil, nations that are all facing serious economic challenges according to the World Bank.

The Brazilian economy has been shrinking since 2011, while the economy in Venezuela also continues to deteriorate. In 2015, 15 years of sustained economic growth came to an end in Ecuador.

Experts say the main challenge facing economic cooperation between China and Latin America is whether Chinese investment could better promote sustainable development that is less risky and more environmentally responsible.

Oil Loans Around the Globe

Take Venezuela as an example. The country’s economic growth has all but ground to a halt leaving its credit rating in tatters. It is already unable to repay the $19 billion in loans that it owes to China, according to Barclays Capital Inc.

Wu Guoping, a senior researcher at the Institute of Latin American Studies, part of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says that Venezuela’s economic difficulties are linked with the inherent limitations of its oil sector.

Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves but produces less than 20 percent of Saudi Arabia’s output because its oil is heavier and so more expensive to extract and refine.

“It’s only profitable if the price of oil is at $60 or higher,” says Wu. But that price hasn’t been seen since November 2014.

Venezuela repays its loans to China with oil at the equivalent value. Many oil-for-loans contracts were signed when the price of oil was high but now the country is under pressure to supply much larger quantities than earlier expected.

According to Reuters, Venezuela started to fall behind with oil shipments to China and Russia in 2016, with the national oil company Petróleos de Venezuela failing to supply oil worth $750 million that year.

As well as missed shipments and refining difficulties (China had to build a new refinery specifically for the heavier Venezuelan oil), it has to be shipped halfway around the world to reach China. Taken together, Wu thinks this is too costly an option for China.

From Exports to Self-Sufficiency

For Latin American countries, including Venezuela, the crucial question is how to use Chinese loans.

“China can’t be the one to trigger sustainability but if Latin America got its act together the Chinese could provide some real funding,” says Kevin Gallagher, a professor at Boston University who studies the region.

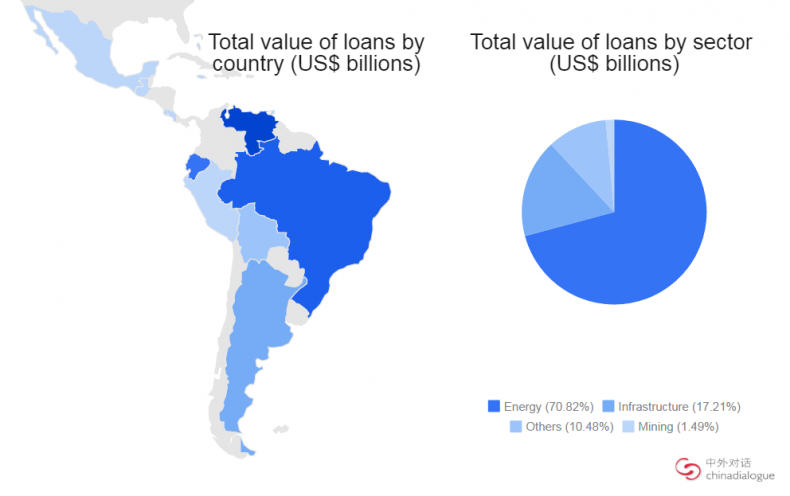

Latin America is rich in natural resources but these are exported as raw materials rather than as processed products. Loans from Chinese banks are focused on energy, mining, and infrastructure.

According to Gallagher, Latin American governments mainly use Chinese loans to build infrastructure linking mines and oil fields to refineries and ports, a far cry from real economic integration or sustainable development.

In Gallagher’s new book, The China Triangle, he says that the situation in many Latin American nations has led to a trade imbalance where countries rely heavily on exports. Profits made from the export of natural resources are reinvested into the extractive sector rather than into sustainable economic and social development.

Domestic politics is a major factor in shaping the investment choices of Latin American governments.

In Venezuela the “Leftist” governing party used the profits from the oil sector to fund populist welfare policies. The Hugo Chavez administration offered free education and healthcare and issued occasional payments to the poor, while infrastructure that has a less visible impact on public welfare (such as expressways) was neglected.

Wu thinks that China’s economic transition is changing the structure of its domestic imports. For Latin America, this is both an opportunity to improve its industries and a challenge.

Gallagher also told chinadialogue that if China’s economic transition goes smoothly, China will need fewer commodities from Latin America. For example, if renewables take a greater market share then China would potentially have less need for oil imports.

In 2013, 9 percent of exports from Latin America and the Caribbean went to China, including 15 percent of the region’s exports from agriculture and the extractive industries.

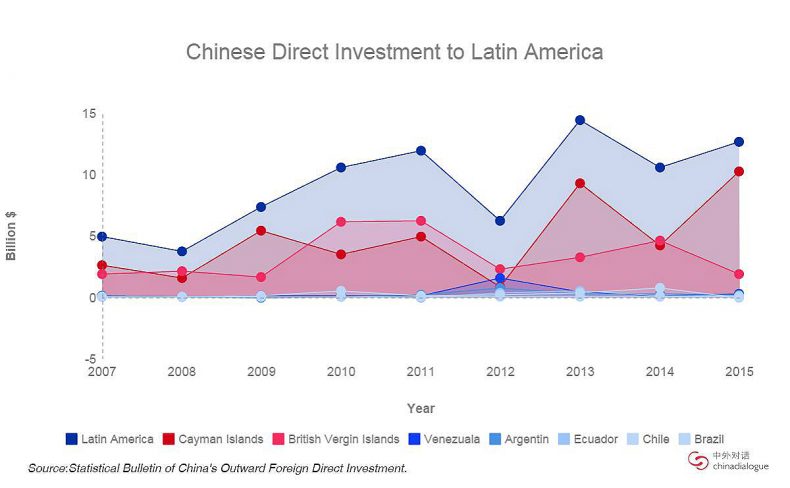

The bulk of the money flowing from China to Latin America is in the form of policy loans rather than direct investment.

China has lent over $140 billion to Latin America since 2005 and is the region’s biggest creditor. But China accounts for less than 10 percent of direct investment in Latin America, and 90 percent of that goes to two offshore financial centers, the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands.

Investment Challenges

Despite the small quantities of direct investment, a failure to adequately research local regulations has still caused problems for Chinese investors. For example, Chinamex, a Ministry of Commerce agency promoting Chinese investment overseas, largely in the Middle East, invested in Dragon Mart Cancun, a retail and residential development in Mexico. But the project was halted just before completion due to the felling of protected trees.

Enrique Dussel Peters, a professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, has said that Chinese firms, whether state-owned or private, do not have an adequate understanding of the region, and that in the Dragon Mart project the Chinese firm’s local partner had failed to explain Mexican laws and systems.

Li Zhiguo, a lawyer specializing in overseas investment, told chinadialogue that Chinese state-owned firms are too fixated on obtaining raw materials rather than understanding local legal environments, and that they lack a mature “corporate culture.” Any of these factors can cause an investment to fail.

Wu Guoping thinks there are at least two factors that cause Chinese firms reputational damage when investing abroad.

First, Chinese companies mainly invest in resources and mining, where there is a higher risk of environmental impacts. Second, investments are mostly undertaken by large state-owned enterprises, which receive support from China’s “policy banks” and have a huge advantage compared with private banks. Government support means they struggle to be competitive in the market.

Wu thinks Chinese firms need to address this competitive weakness and give greater consideration to the rate of return on project investments, particularly when investing in infrastructure in Latin America.

Wu says that as China’s overseas investments expand, the competitiveness of Chinese firms in Latin American markets will increase. This will improve the reputation of Chinese firms as informed financial market players and help to avoid unnecessary investment risks.

Zhang Chun is a senior researcher at chinadialogue.

This post was originally published by chinadialogue and appears with kind permission.