On Thursday, China and the ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) announced that they had finalized a framework for a code of conduct for the disputed South China Sea. The announcement was made first by the Chinese foreign ministry. China and four ASEAN member states — Malaysia, Vietnam, Philippines, and Brunei — are claimants to disputed features in the South China Sea. (Taiwan is also a non-ASEAN claimant in the South China Sea.)

The Chinese foreign ministry first made the announcement that a framework agreement had been reached by consensus following a meeting between then eleven parties in the Chinese city of Guiyang. The Chinese foreign ministry’s announcement did not go into detail about the framework’s contents not has the document been publicly released as of this writing. The Guiyang meeting was the 14th senior officials’ meeting on the implementation of the November 2002 non-binding Declaration on the Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea (DOC).

All parties “uphold using the framework of regional rules to manage and control disputes, to deepen practical maritime cooperation, to promote consultation on the code and jointly maintain the peace and stability of the South China Sea,” the official Chinese statement released on Thursday noted. Liu, however, when asked by reporters if the framework would be binding, noted that he could not give a definite answer.

“I’m sure it will be a very important point of discussion in future consultations,” he said, suggesting that Thursday’s framework agreement is likely a general agreement. He added that the framework outlined various components that may eventually make it into a code of conduct, but that “these are only the elements of the COC, not the eventual rules of the COC.”

Meanwhile, Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin noted on Chinese state television that the framework agreement took the concerns of all parties into account. “We hope that our consultations on the code are not subject to any outside interference,” Liu said, according to Reuters, in a message likely pointed at the United States.

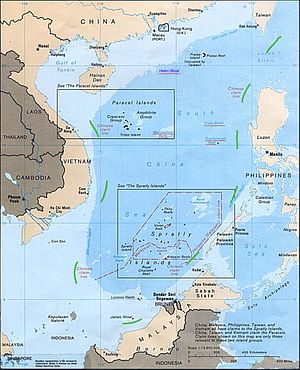

Thursday’s declaration follows an April ASEAN leaders’ meeting that notably excluded any reference to China’s assertive behavior in the South China Sea, including its construction of seven artificial islands in the Spratly group. ASEAN is currently chaired by the Philippines, whose leader Rodrigo Duterte has pursued a bilateral rapprochement with Beijing since being sworn into office in June 2016.

As South China Sea analysts await the public release of the framework, several questions persist about the nature of the agreement. Notably, observers will be watching for any indication that the framework includes the sort of binding provisions that have long been expected but seen as unattainable given what once seemed as an unbridgeable gap between China and the forward-leaning ASEAN claimant states, including Vietnam and the Philippines under the previous government led by Benigno Aquino III.

Under the Philippines’ chairmanship of ASEAN, China’s relative bargaining position has clearly improved with the Southeast Asian grouping. ASEAN has long been divided over the issue of the South China Sea, with some of the non-claimant states in particular (with the notable exception of Indonesia and Singapore) having expressed reservations about pushing back too hard against Beijing on the issue. Most notably, in 2012, ASEAN leaders failed to issue a joint statement after a summit in Cambodia over these divisions.

Beijing is also eager to shift the debate over the South China Sea away from the July 2016 ruling by a five-judge tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague. That ruling found that China’s capacious nine-dash line claim in the South China Sea had no validity under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. The award resolved a case that the Philippines under Aquino had filed in early 2013 after the highly publicized 2012 stand-off with Beijing over Scarborough Shoal.

In November 2002, China and the ten ASEAN states signed the non-binding Declaration of the Conduct (DoC) of Parties in the South China Sea. That document saw all eleven parties pledge their commitment to eventually conclude a binding code of conduct. That document noted that “the adoption of a code of conduct in the South China Sea would further promote peace and stability in the region.”