The world has witnessed a surprising rise in anti-globalization sentiment, epitomized by the United Kingdom’s Brexit and U.S. election of Donald Trump. But what is even more surprising is the country that has stepped in to defend the value of free trade: the People’s Republic of China.

On May 14-15, China will be hosting its largest diplomatic event of the year, the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. This forum supports China’s New Silk Road initiative to increase economic connectivity between Asia, Europe, and Africa through billions of dollars in infrastructure investments. Heads of state from over two dozen countries will be in attendance, including most Asian leaders.

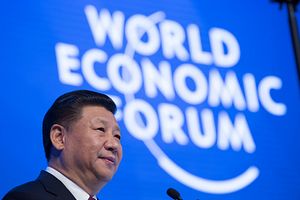

The Belt and Road Forum follows Chinese President Xi Jinping’s appearance at January’s World Economic Forum in Davos. In his speech, President Xi strongly supported economic globalization, stating that “we must remain committed to developing global free trade and investment… and say no to protectionism.”

President Xi’s comments stand in stark contrast with the recent policy shifts in Western Europe and the United States.

The same day as President Xi’s speech in Davos, UK Prime Minister Theresa May laid out her plans for a “hard Brexit” that includes leaving the EU single market. Meanwhile, although Euroskeptic candidate Marine Le Pen did not prevail in the French presidential runoff election this past weekend, she still received over 10 million votes, making her the most successful anti-EU French candidate to date.

In the United States, President Trump appeared set to withdraw from the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on his 100th day in office, before abruptly reconsidering. This follows one of his first executive orders, which formally withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations. These actions have demonstrated Trump’s willingness to reduce free trade and curtail the development of economic globalization because of his skepticism of its value for American workers.

It has been a shocking reversal to see the U.S. and UK reject major free trade agreements, with other nations potentially following suit.

Adding to the unpredictability of recent events, China has taken the helm as the leading international power to promote economic globalization. With a government founded on communist ideology and initially ruled by a leader set on rooting out so-called “capitalist roaders,” China is a highly unlikely champion of international free markets. Though it began developing a market economy four decades ago, it was not until 2001 that China acceded to the World Trade Organization and fully integrated into the world economy. China’s subsequent ascension from a new member of the international economic order to one of its foremost proponents is both a rapid and unexpected development.

China’s recent positioning as a strong advocate of international trade is also interesting given its rocky path towards free trade principles. As a WTO member, China has collected the third highest number of complaints against it for unfair trade practices, though at rates still below those of the U.S. and EU. International trading partners such as the U.S. have criticized China for employing export restraints, foreign investment restrictions (including requiring technology transfers), export dumping, and other trade barriers. Other behaviors restricting free trade, such as subsidizing domestic agriculture and protecting strategic industries, have been exhibited by many other countries in addition to China.

China’s evolution into an advocate of open markets began with Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up policies in December 1978. In order to explain the shift away from traditional communist doctrine, Deng termed the new system “socialism with Chinese characteristics.” China’s unique mix of a communist party-controlled state with a market-based economic system was framed as a stage in China’s path of socialism, tailored to its current situation.

China’s recent push for greater economic globalization can similarly be coined “globalization with Chinese characteristics.” Rather than welcoming economic, political, and cultural globalization, China has rejected the influence of these latter two international forces as destabilizing. Government campaigns against “Western values” have in fact gained new force under President Xi Jinping. Instead, China has embraced a narrower view that only economic globalization is appropriate for its unique domestic context.

Other countries such as the U.S. have argued that economic liberalization should go hand in hand with social and political reforms around democratization, human rights, and civil liberties. So-called modernization theorists have even studied whether democratization is an inevitable result of economic development, demanded by a nation’s newly formed middle class.

China has so far bucked this trend towards democratization, with the communist party maintaining rigid one-party control of the country. It has resisted political and cultural globalization, restricting access to information on the internet through the “great firewall” and limiting the ability of foreign NGOs to operate in China.

By blocking out foreign influence, the Chinese Communist Party has been able to maintain authoritarian control in China. According to Freedom House’s 2017 Freedom in the World report on political rights and civil liberties, China rates as “not free” with a score of 15 out of 100. This scores China as worse on political rights and civil liberties than Russia, Iran, and the Congo, among other countries. As the U.S. Department of State’s 2016 Country Report on Human Rights Practices in China notes, China continues to censor the media, withhold due process in judicial proceedings, and illegally detain and harass journalists, human rights lawyers, and dissidents.

With the U.S. and Europe now focusing inward, China is poised to capitalize on this unique moment to spread its model of economic globalization detached from political and cultural openness. By ramping up international investment through the Belt and Road initiative, China is providing concrete proof to illiberal states in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East that there is much to gain from embracing “globalization with Chinese characteristics.”

The upcoming Belt and Road Forum will provide a valuable glimpse into whether this Chinese model of globalization will gain traction as a new international standard.

Jason Zukus is a joint degree Master of Business Administration and Master of Public Policy candidate at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and Harris School of Public Policy.